Hg wells house london

Former London Home of Prolific Sci-Fi Writer H.G. Wells Lists for £13.95 Million

Skip to main content

By Liz Lucking

| | Mansion Global

“H.G. Wells Lived and Died Here” reads the inscription on the commemorative blue plaque affixed to the stucco facade of a newly listed mansion in London.

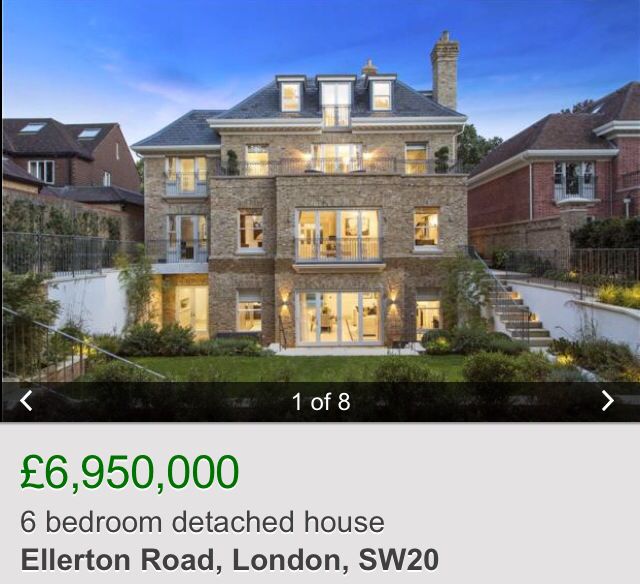

Asking £13.95 million (US$18.7 million), the house was home to the prolific English author and so-called “father of science fiction,” from 1933 up until his death in 1946, according to a news release from listing agency Aston Chase.

The property, which was listed at the end of November, is part of Hanover Terrace, a cluster of 20 conjoined townhouses directly across the street from Regent’s Park.

The Grade I-listed terrace was designed in 1822 by John Nash, a famed British architect of the Regency and Georgian eras who is responsible for some of the U.K.’s grandest designs, such as Buckingham Palace, Marble Arch and Brighton’s Royal Pavilion.

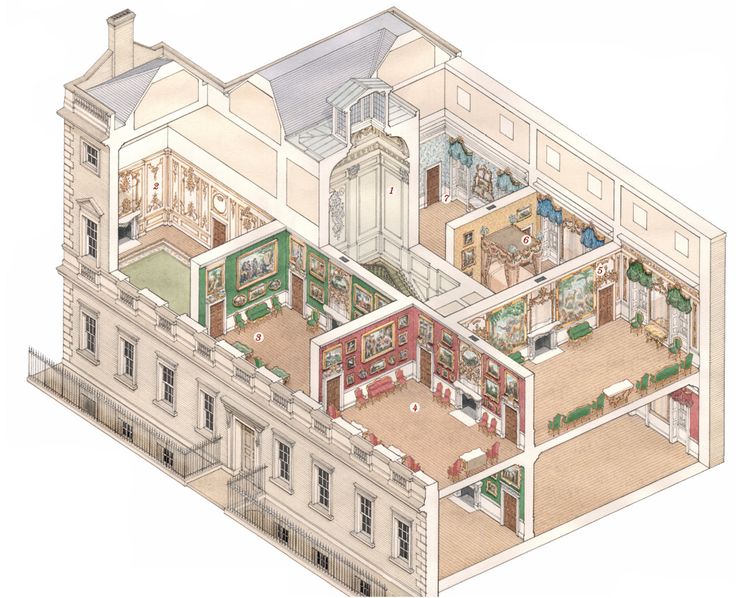

Spanning close to 5,000 square feet across five floors, the three-bedroom home was thoroughly restored in 2004, and still retains a number of its original period features, including cornicing and fireplaces, according to the release.

Along with coveted, unobstructed views over Regent’s Park, the house has a full-floor formal reception room, a balcony, and a study with bespoke bookcases.

There's also a wine cellar, a safe room, a sauna and a self-contained staff accommodation.

Mansion Global couldn’t determine the owner of the home, or how much they paid for it.

“Alongside the main residence, purchasers of [the home] benefit from a mews house, which can host guests or be utilized as a private home office,” Mark Pollack, director and co-founder at Aston Chase, said in the release. “This property is truly one of a kind with a colorful history, commemorated by the blue plaque outside.”

“This property is truly one of a kind with a colorful history, commemorated by the blue plaque outside.”

From Penta: Art Buyers Expect Online Shift to Last, Survey Finds

The blue plaque program, exclusive to London—though other U.K. cities have their own, unaffiliated, schemes—has been running since 1866 and pays homage to some of the city’s most notable past residents.

The one commemorating Wells is one of three on the Hanover Terrace, according to Historic England, who runs the program. It’s joined by one at No. 10 for composer Ralph Vaughan Williams, and another at No. 11 for architect Anthony Salvin.

Wells, who was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature four times, is best known for novels including “The War of the Worlds,” “The Island of Doctor Moreau” and “The Time Machine.”

Against advice from friends, he stayed at the home during World War II and the Blitz—during which London was bombed for 57 consecutive nights—and remained there until his death in 1946 at the age of 79, according to the release.

The new owner “will be buying an iconic home, which seldom comes to market, as well as a piece of British history,” Mr. Pollack said.

Read Next Story

For the optimum Mansion Global experience, please turn off any ad blockers and refresh this page.

H.G. Wells House - 17 Church Row Hampstead.

- 17 Church Row, Hampstead, London NW3

- Hampstead Underground

THE NOT SO INVISIBLE MAN

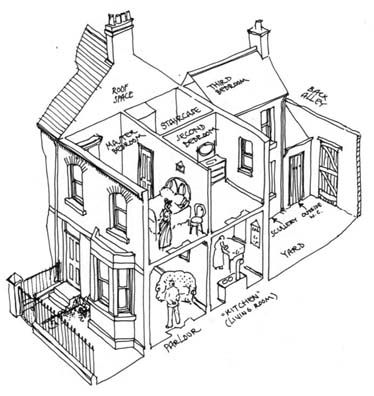

In August 1909 the author H.G. Wells and his wife, Jane, together with their two sons, George Philip (known as Gip) and Frank Richard, moved in to the terraced property at number 17 Church Row, Hampstead.

They moved here from the much larger Spade House, their purpose built mansion that he had had constructed in 1901, and which overlooked Sandgate near Folkstone.

Despite its numerous bedrooms, 17 Church Row must have seemed decidedly cramped compared to what they had been used to over the previous years.

Their move here was intended as a fresh start which came about as a result of a particularly tumultuous period in their decidedly unconventional marriage, because, immediately prior to their arrival in Hampstead - and also during their time here - the 43-year old Wells was embroiled in an affair with a 21-year old woman who, just four months after their arrival, would give birth to Wells's daughter on 31st December 1909.

A LITERARY LOTHARIO

H. G Wells

At first glance Herbert George Wells (1866 - 1946) might not strike you as the ultimate lothario.

He was, after all, short of stature, wide of girth, follicely challenged, and his voice was unusually high pitched.

Yet, there was something about this vertically challenged titan of literature that made him irresistible to women and ensured him a steady stream of illicit affairs, many of them with the resigned consent of his wife, Jane Wells.

Indeed, his relationship with Jane had begun as an extra-marital affair and he had left his first wife, Isabelle, to marry her in 1894.

During their marriage Jane came to view her husband's promiscuity as "a sort of constitutional disease" and, therefore, gave her consent for his regular dalliances that saw his involvement with a range 0f lovers, most of them strong-minded women.

AMBER REEVES

By 1909, he had become embroiled in a steamy affair with Amber Reeves (1887 - 1981), a student at Cambridge University whom he had known since she was seventeen, although he always maintained that she was twenty-one when their friendship blossomed into romance and, according to Wells's own account, "...we contrived a meeting in Soho, when we became lovers in the fullest sense of the word..."

According to Wells, Amber was "...a girl of brilliant and precocious promise ... [with] a sharp, bright, Levantine face under a shock of very fine abundant black hair, a slender nimble body very much alive, and a quick greedy mind."

The lovers were soon renting a room at 126 Warwick Street, behind London's Victoria Station, where they were known as Mr..jpeg) and Mrs. Graham Wells - although their liaisons were conducted at an eclectic mix of locations, both in London and further afield; including "among bushes in a windy twilight near Hythe"; inside a church - possibly at Paddlesworth (Wells was able to recall the surroundings, but not the location) - that they had persuaded the sexton to unlock for them, ostensibly so they could explore the belfry; and in the woods as they headed home from the aforementioned church.

and Mrs. Graham Wells - although their liaisons were conducted at an eclectic mix of locations, both in London and further afield; including "among bushes in a windy twilight near Hythe"; inside a church - possibly at Paddlesworth (Wells was able to recall the surroundings, but not the location) - that they had persuaded the sexton to unlock for them, ostensibly so they could explore the belfry; and in the woods as they headed home from the aforementioned church.

THE H. G. WELLS SCANDAL

At first, they managed to keep their relationship a secret.

But, inevitably, word of it dribbled out and the habitually promiscuous author and his latest mistress - whom he was now referring to affectionately as Dusa, short for Medusa, on account of her unruly hair - found themselves the talk of polite society, and a public scandal was soon in the offing.

Amber's father, William, was the New Zealand High Commissioner to London, and he and his wife, Maud, were both members of the Fabian Society, as was Wells.

At first, they remained blissfully unaware of their daughters relationship with the married older man who was a cherished family friend.

When he eventually found out, William Reeves was furious at Wells's betrayal of their friendship - not to mention the seduction of his daughter - and, according to the author Compton Mackenzie, he declared that Wells should be shot for his appalling behaviour, and he duly took up a position in a window at the Savile Club - of which both he and Wells were members - armed with a loaded pistol to await the arrival of his daughter's seducer.

The embarrassment of this incident caused the club to politely enquire of Wells if he wouldn't mind resigning his membership?

Amber's family and friends, meanwhile, were making determined efforts to end the affair, with several of her boyfriends even offering to rescue her from the clutches of the married father-of-two by marrying her themselves. Among these noble suitors was a young lawyer by the name of George Blanco White.

WHAT HIS WIFE THOUGHT

Jane Wells, meanwhile, had no real objection to her husband having yet another affair, even going so far as to visit Amber and then, in response to a subsequent letter from her husband's mistress, replying with an affectionate missive which ended "Love to you, my dear from your Jane."

THEY ARRANGE A FINAL MEETING

126 Warwick Street

Now Warwick Way

Under intense pressure from family and friends alike to end the affair, Amber duly phoned Wells and arranged a final meeting at their Warwick Street love nest at which her opening gambit was the decisive request "give me a child, whatever happens".

Wells could have easily declined by pointing out that to do so would, undoubtedly, cause a scandal that could end his career.

But, since abstinence and restraint were two words that were markedly absent from his considerable vocabulary, he, instead, happily obliged and even promised to dedicate his novel after next to their, as yet, un-conceived "daughter" - Anna Jane, or A. J. as he put it in his dedication.

J. as he put it in his dedication.

Soon, Wells was planning their future together and he wrote to tell her that:-

"I've had things out with Jane. Item she is to have a baby. I know Spade House [the family home at the time] is to be over. Then you and I will live together. Jane will have a house in London & you will have a little flat for your alleged home..."

JANE WELLS OBJECTS

However, Jane had no intention of giving in to her errant husband's self-centred demands.

An affair was one thing, divorce was an entirely different matter and there was no way whatsoever that she was going to give up on being Mrs. Wells.

In a letter to Amber, in which he demonstrated a total lack of empathy, bordering on naivety, towards his wife's feelings, Wells complained that Jane had objected to him displaying a photograph of his mistress in the family home and explained how they had " talked for an hour about your photograph. It was going to hurt her - when I'm away she would want to smash it - your are getting all over her life and things like that. "

"

The result of this tense exchange between he and his wife, he wrote, was that he ended up "crying like a baby" and, having stuck his head under the bed clothes, he got a nose bleed that "...smothered myself & and the bed & the pillow with blood..."

THE FLIGHT TO FRANCE

In May 1909, with the pressure and the scandal mounting, H. G. Wells and Amber Reeves met at Victoria Station and decamped across the Channel where they rented a furnished chalet in France.

THE RETURN TO ENGLAND

However, as Wells later explained, "I found the idea of a divorce from Jane intolerable. Neither of us relished the prospect of wandering about the Continent, a pair of ambiguous outcasts - quite possibly hard up..." and it wasn't long before the love birds were heading back to England, Wells returning to his wife and family, and the pregnant Amber marrying George Rivers Blanco White, a union that, she later claimed, was arranged between White and "...H.G, but I have always thought it the best that could possibly have happened. "

"

THE MOVE TO 17 CHURCH ROW

In August 1909, the Wells family arrived at 17 Church Row intent on making a fresh start.

The, comparatively cramped conditions weren't the only thing that they found difficulty coming to terms with.

When initially viewing the house, they had not noticed the proximity of the large overspill burial ground of nearby St. John's Church, which was located just a short distance from their front door.

They thus had to contend with a constant stream of horse drawn funeral processions solemnly filing past in the street outside, just a few feet from their front window.

Wells was soon finding the house far too cramped for his liking, and he took a small flat in Candover Street, off Great Portland Street, which he frequently decamped to "...for purposes of work, and nervous relief...," his code for further illicit liaisons with "various friendly women."

THE RELATIONSHIP WITH AMBER CONTINUES

Meanwhile, he continued to see Amber, even going so far as to rent a cottage for her in Woldingham in Surrey at which he often visited her. The fact that he was often there at the same time as Blanco White surely proving awkward for all concerned?

The fact that he was often there at the same time as Blanco White surely proving awkward for all concerned?

Jane wasn't in the least bit perturbed by the continuation of her husband's extra-marital fling. After all, she was now secure as the Mrs. Wells; and so she allowed her husband to continue seeing his pregnant paramour and to offer emotional support - even going so far as to send their sons to keep Amber company when she was in London.

On 31 December 1909, Amber gave birth to their daughter, Anna-Jane, who did not learn that her real father was H. G. Wells until she was 18.

Blanco White, however, was tiring of the situation and threatened legal action against Wells unless he stayed away from his wife.

Realising that such an action would be hugely detrimental to his reputation, Wells reluctantly agreed to keep out of Amber's life for at last the next two years.

Amber Blanco White went on to become a major force in British feminism, a respected scholar and a celebrated author in her own right, with a total of eight books to her name.

She had two further children by her husband, and lived for many years on nearby Downshire Hill in Hampstead.

She died on 29th December 1981 at the ripe old age of 94 and is survived by several grandchildren, one of whom is the mathematician Dusa McDuff.

Her obituary in The Times remembered her as a "collaborator for a time of H. G. Wells in his campaign to break the taboos of Victorian and Edwardian morality..."

A FAMILY HOME

Back in their Hampstead home, Wells immersed himself in writing the book that would become his greatest comic novel The History of Mr. Polly, although, as he later recalled, he found himself in such an emotional turmoil that he wrote much of it "weeping bitterly like a frustrated child.".

His other books, written or published during his time here, were Tono-Bungay ; Ann Veronica; The Sleeper Awakes; The New Machiavelli; and Marriage.

He relaxed from his busy writing schedule with the works of classical composers - albeit, since the gramophone and radio had yet to become universally available, he actually peddled the music out on a pianola that had been recommended to him by his great friend, and a frequent visitor to the house, George Bernard Shaw.

The children were home schooled under the tutelage of their governess, Mathilda Meyer, and by the aptly named Mr. Classey. Gip even had an operation to remove his appendix in the house's study in April 1910.

At bed time the boys would sit by their father's side as he would draw comical pictures for them, although he was also not adverse to administering corporal punishment should they misbehave.

Wells held frequent weekend dressing-up parties, games of charades and Parlour games in which visitors to 17 Church Row were expected to take part.

FLOOR GAMES IN HAMPSTEAD

A popular form of entertainment, both for himself and the boys, was the "floor games" that they liked to play in the schoolroom and in the garden.

When he included these games in his book The New Machiavelli, the publisher Frank Palmer commissioned him to write a book on the subject and the light-hearted volume Floor Games, was duly published in December 1911.

Standing outside the brilliant-white exterior of 17 Church Row, you can picture Wells, Gip, Frank and their numerous visitors crawling around the floors and garden playing the games that are jovially described in its pages.

Indeed, its chatty tone makes delightful reading, even today.

Section one of the book, for example, begins with the following wonderfully whimsical instruction:-

The jolliest indoor games for boys and girls demand a floor, and the home that has no floor upon which games may be played falls so far short of happiness. It must be a floor covered with linoleum or cork carpet, so that toy soldiers and such-like will stand up upon it, and of a color and surface that will take and show chalk marks; the common green-colored cork carpet without a pattern is the best of all.

Or, how about this delightful gem concerning uses for the floor:-

I will now glance rather more shortly at some other very good uses of the floor, the boards, the bricks, the soldiers, and the railway system - that pentagram for exorcising the evil spirit of dullness from the lives of little boys and girls. And first, there is a kind of lark we call Funiculars. There are times when islands cease somehow to dazzle, and towns and cities are too orderly and uneventful and cramped for us, and we want something - something to whizz. Then we say: "Let us make a funicular. Let us make a funicular more than we have ever done. Let us make one to reach up to the table."

Then we say: "Let us make a funicular. Let us make a funicular more than we have ever done. Let us make one to reach up to the table."

No wonder the book has, in recent years, enjoyed a resurgence amongst child psychologists as a model for learning through play.

You can read the full text of Floor Games here.

MORE AFFAIRS

However, it wasn't long before Wells's roving eye was once more swiveling in its socket and, in late 1910, he began an affair with the Australian born widow of a German aristocrat, Elizabeth von Arnim, whom he nicknamed "Little e", whilst she reciprocated by giving him the pet name "Geak."

Once again the unflappable Jane - who, as it transpired, was a great fan of the gardening books, such as Elizabeth and her German Garden, of which her husband's latest paramour was the bestselling author - accepted the affair and felt secure in the knowledge that the strong willed and extremely independent Elizabeth was unlikely to steal another woman's spouse.

Their liaisons took place at a flat in London's West End, at a succession of country inns where, so Wells enthusiastically reported, they managed to break two beds, and (somewhat uncomfortably?) on piles of pine needles - ouch!

One of their sessions occurred on a surface that managed to prophetically, but unintentionally, involve Wells's next mistress.

As Wells later reported:-

"One day we found in a copy of The Times we had brought with us, a letter from Mrs. Humphrey Ward denouncing the moral tone of...a rising young writer, Rebecca West, and having read it aloud, we decided we had to do something about it. So we stripped ourselves under the trees as though there was no one in the world but ourselves, and made love all over Mrs Humphrey Ward. And when we had dressed again we lit a match and burnt her."

Back in London, he discovered that Cicely Fairfield, who was writing under the pseudonym of Rebecca West - and who was, therefore, the very same Rebecca West whom Mrs Humphrey Ward had denounced - had enthusiastically reviewed his latest book and he duly invited her to lunch.

Wells would later say of her that "I had never met anything like her before, and I doubt if there was anything like her before", and it wasn't long before the inevitable happened and she had replaced "Little e" as his mistress, with, according to some accounts, their first kiss taking place here at 17 Church Row over tea!

"Panther" and his "Jaguar" - their pet names for each other - were soon embroiled in a full blown affair and by 1914 she was pregnant, giving birth to their son, Anthony West (1914-1987) in the August of that year.

You can watch Dame Rebecca West talking about her time With Wells on this BBC clip.

THE WELLS'S LEAVE HAMPSTEAD

By this time, however, the Wells family had moved to the Old Rectory at Little Easton, near Dunmow in Essex.

Although their time here had been tinged with turmoil, their had also been many happy times and it doesn't take too much imagination to stand in the street outside and picture the likes of George Bernard Shaw, Henry James, Arnold Bennett, and even Winston Churchill, traipsing along Church Row, to knock on the door of number 17 to be greeted by the high pitched tones of the plump little lothario who many now regard as the father of Science Fiction.

NOT ONLY H. G. WELLS BUT ALSO PETER COOK

17 Church Row would go on to see another celebrity occupant when, in 1965, it became the home of the comedian Peter Cook and his wife, Wendy.

Together with his comedy partner, Dudley Moore, Peter would work on scripts in the attic of the house, indeed Wendy later recalled how she would often hear them roaring with laughter at the latest sketches and jokes they had come up with.

WATCH ONE OF THEIR SKETCHES

EVENING DINNER PARTIES

In the evenings he and Wendy would entertain the likes of Keith Richards, John Lennon and Paul McCartney at dinner parties in the basement kitchen.

Strange to think that the plump little man who, sixty years before them, would have waddled along Church Row to that same front door, through which they all entered the property, and whose staid appearance belied an unconventional streak that could easily have put any one of them to shame, would have felt right at home amidst the free love haze of the Swinging Sixties.

where is located and what to see nearby

On the coast of the English county of Kent stands the former home of one of the greatest science fiction writers

View of Sandgate Embankment with HG Wells House (Green Building) HG Wells House Memorial plaque on house 1890 photograph of HG Wells

nine0002 In 1896, H. G. Wells and his family traveled to the seaside town of Sandgate for the first time to recover from failing health, which he believed had been worsened by the stress and pollution of London's environment. Moving from London really improved the mental and physical health of the English writer and affected his productivity. It was during this time that Wells wrote many of his greatest books, including The Island of Dr. Moreau, The War of the Worlds, and The Invisible Man. At Sandgate, Wells regularly hosted many famous fellow writers and friends such as Joseph Conrad, Arnold Bennett, George Bernard Shaw, Winston Churchill, Ford Madox Fox, Edward Sassoon and Henry James. nine0005

At Sandgate, Wells regularly hosted many famous fellow writers and friends such as Joseph Conrad, Arnold Bennett, George Bernard Shaw, Winston Churchill, Ford Madox Fox, Edward Sassoon and Henry James. nine0005

Thanks to his famous novels, Wells went down in history as one of the most influential writers of the early 20th century. He is often called the father of science fiction. However, his provocative books such as A Modern Utopia, as well as his vocal unconventional views on monogamy and marriage, have raised eyebrows and become a source of gossip. Wells irritated with his penchant for womanizing and extramarital affairs, as well as infidelity at the local and social level of London. Not surprisingly, this ended up causing a scandal in the small Kentish town, leading to the writer's expulsion from the city. nine0005

Despite this, even after Wells' death in 1946, the city of Sandgate continued to be associated with the author, and distinguished writers, including Jorge Luis Borges, made special trips to the city to see the house where Wells lived and wrote his most famous works. Today, Sandgate has come to realize his connection to this famous historical resident. Mentions of the writer are found throughout the city, including in the local society of H. G. Wells, which annually holds a short story competition in the neighboring city of Folkestone. A small plaque marks the writer's first home in Sandgate, where he lived from 1896 to 1901 until he built the family home known as the Spade House.

Today, Sandgate has come to realize his connection to this famous historical resident. Mentions of the writer are found throughout the city, including in the local society of H. G. Wells, which annually holds a short story competition in the neighboring city of Folkestone. A small plaque marks the writer's first home in Sandgate, where he lived from 1896 to 1901 until he built the family home known as the Spade House.

Good to know

The house is located on the Sandgate waterfront, close to the castle. The outside of the building and the plaque can be seen for free, but the house itself is private property and is not open to the public.

houses science fiction history literature tablets authors

Authors: Ekaterina Ivanova, Alexey Kalinin

Where to stay

Places nearby

Might be interesting

Incredible everyday.

Translated from English by M. Landor

Translated from English by M. Landor Wells rarely commented on his fantastic books. He writes two prefaces to his early novels in his declining years, when an extensive critical literature already existed about his work. nine0044

In an article that precedes the American edition of The Time Machine (1931) 1 , he recalls his hungry journalistic youth, tells about the concept of the novel, which brought him worldwide fame.

The 1934 article was a preface to Wells's one-volume book published by Knopf under the title "Seven Famous Novels" 2 . This article succinctly and accurately defines his creative method. Here Wells gives his advice to science fiction writers. He developed, unlike Jules Verne, incredible hypotheses, but at the same time he warned his followers against being carried away by fiction. The heap of inventions destroys the artistic illusion; a novel that has become detached from everyday life ceases to excite readers. According to Wells, fantasy helps to pose acute social problems, it goes well with satire. nine0044

According to Wells, fantasy helps to pose acute social problems, it goes well with satire. nine0044

These articles are printed below: the preface of 1931 - in abbreviated form, the preface of 1934 - in full.

1

The Time Machine was published in 1895. It is easy to see that it was written by an inexperienced hand; but there was a certain originality in it that saved it from oblivion: after a third of a century, publishers and, perhaps, even readers can still be found for it. In its final form - apart from some minor corrections - the book was written in Sevenoaks, Kent. Its author earned his living as a journalist. There came a lean month when scarcely one of his articles was published or paid for in any of the newspapers where he was accustomed to collaborate; since all the newsrooms in London that were inclined to tolerate him were well supplied with as yet unpublished articles, it seemed hopeless to write anything else until the blockage cleared up. Rather than experience this sad change in his position, he wrote this story, hoping that it would make its way to the market. He remembers how he wrote it one late summer evening, at the open window, and the unpleasant hostess, standing in the darkness outside, grumbled that he was constantly burning her lamp: the hostess assured the sleeping world that she would not go home until this lamp was burn; he wrote to the accompaniment of her grumblings. And he remembers discussing this book and the ideas behind it, walking in Knowle Park with his sweet companion, who had been so supportive of him in those turbulent and hungry years, when the future was vague and full of hope. nine0005

Rather than experience this sad change in his position, he wrote this story, hoping that it would make its way to the market. He remembers how he wrote it one late summer evening, at the open window, and the unpleasant hostess, standing in the darkness outside, grumbled that he was constantly burning her lamp: the hostess assured the sleeping world that she would not go home until this lamp was burn; he wrote to the accompaniment of her grumblings. And he remembers discussing this book and the ideas behind it, walking in Knowle Park with his sweet companion, who had been so supportive of him in those turbulent and hungry years, when the future was vague and full of hope. nine0005

The main idea seemed to be his own discovery in those days. He saved it for a long time, hoping one day to develop it in a more extensive book than The Time Machine, but the urgent need to write something salable forced him to resort to it immediately. As the astute reader will notice, this is a very uneven book: the discussion with which it opens is much better thought out and written than subsequent chapters. A stunted story grows from a very deep root. The first part, which explains the main idea, has already seen the light in 1893, at the National Observer at Henley's. The second part was written in Sevenoaks in 1894 with great effort.

A stunted story grows from a very deep root. The first part, which explains the main idea, has already seen the light in 1893, at the National Observer at Henley's. The second part was written in Sevenoaks in 1894 with great effort.

The main idea is now in the public domain. It was never a special idea belonging to the author. Other people approached her. During student disputes in the 1980s, held in the laboratories and debating society of the Royal College of Science, the author came up with it, and he used it several times in various forms before putting it in the basis of the book. This is the thought of Time as the fourth dimension; the three-dimensional present turns out to be part of a universe that has four dimensions. From this point of view, the only difference between time and other dimensions is that consciousness moves along it; this constitutes the movement of the present. Obviously, there can be a different "present" - depending on the direction in which the moving part of the universe is taken; thus expressed the idea of relativity, which came into scientific use much later.