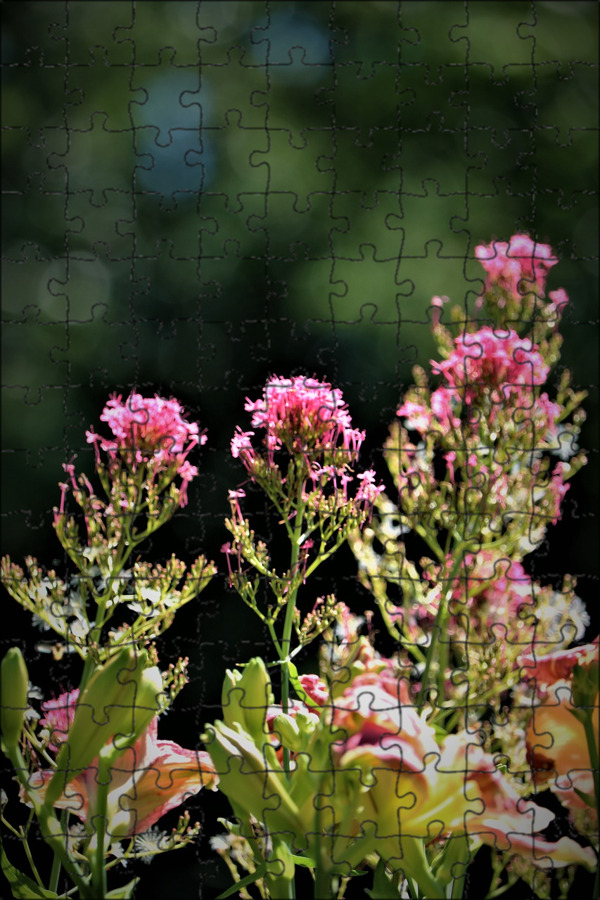

Wildflower meadow plants

Planting for Pollinators: Establishing a Wildflower Meadow from Seed [fact sheet]

Download ResourCE (.pdf)

This fact sheet received the American Society of Horticultural Science 2019 Award for Outstanding Fact Sheet - Extension Division.

Why Plant Wildflowers?

Native bees and other pollinators are essential to the successful production of many fruit and vegetable crops and the reproduction of many plant species in our surrounding environment. Wildflower meadows and gardens are extremely valuable habitat, providing floral resources, nesting sites and a protected environment for hundreds of bee species, moths and butterflies, and other insects. Many birds, bats, small mammals and some amphibians also thrive on the food and shelter that a meadow ecosystem provides.

Meadows provide many important ecosystem services including infiltration and filtration of stormwater, carbon storage, nutrient recycling, soil building, and provisioning of food and shelter for biodiverse communities of flora and fauna. By establishing native perennials and grasses in a dense and diverse meadow planting, property owners can enjoy the beauty of a succession of flowers and plant forms and experience a renewed connection with nature. Done properly, wildflower meadows are ecologically-friendly landscape components that, once established, have minimal maintenance requirements.

Soil testing can provide you with useful information regarding pH and organic matter content, but wildflowers generally prefer low fertility sites. Determine whether the soil tends to be wet or dry, and if the site gets full sun, filtered sun or shade.

An established meadow should be dense enough to out-compete weeds and should provide a succession of diverse flowers to support pollinators.Choosing a Site

Not all wildflowers are suitable for all conditions. A site with full sun and good drainage is ideal for many species, but partial shade and/or wet areas can be tolerated by many others. Consider your site and soil conditions carefully in order to select an appropriate wildflower mix.

It’s best to start in a small area, but consider 400 square feet to be a minimal size for a wildflower meadow – this space can support a good diversity of wildflower species. Some types of wildflowers get quite tall and may tend to lean or flop, but they will help hold each other up if planted densely in an area where they will not interfere with walkways or other landscape features. A wildflower meadow is informal by nature, and can be a bit wild and untidy looking at certain times of the year, so locate it where it will be viewed from a distance of several meters or more. For a neater, more designed meadow look, purchase small transplants instead of starting from seed, and plant in intentional groupings as in a garden.

A place where bees can come and go safely with little disturbance or exposure to pesticides or other household chemicals is ideal. Many native bees need patches of bare soil nearby in which to make their nests; others will nest in small holes in dead wood or stems, in cavities in stone walls or in leaf litter or debris piles. These features are often found along the edges of fields or woodlands and should be preserved. Some people build or purchase bee boxes or bee houses to encourage mason bees and other solitary bees to nest near their crops or gardens.

These features are often found along the edges of fields or woodlands and should be preserved. Some people build or purchase bee boxes or bee houses to encourage mason bees and other solitary bees to nest near their crops or gardens.

Seed Mixes and Species Selection

There are many wildflower mixes available from reputable seed companies1 , or you can design your own mix. Pre-made mixes may be convenient, but must be selected carefully to avoid paying for species that are unlikely to be successful in New England, or that might be overly aggressive. Less expensive mixes frequently contain a higher proportion of grasses than desired for good pollinator habitat.

Knowing your site characteristics (wet, medium or dry soil and full sun, filtered sun, or shade, at a minimum) is essential to understanding which species will thrive on your site and create a mixed meadow that knits together in a mosaic of colors and textures.

An ideal meadow mix will provide a continuous sequence of bloom from a dozen or more native perennial wildflowers (a.k.a. forbs). A few native warm-season grasses should be included to create habitat and shelter for many organisms, and to create dense cover that suppresses weed growth. Some mixes contain annuals, which will give you firstseason color but are generally not native species and not sustainable over time. You are better off in the long term to spend your money on perennial species. By including black-eyed Susan, and perhaps dotted horsemint, you can still get some blooms the first season to satisfy the need for color and provide some flowers for bees.

A suggested wildflower mix for medium to dry sites in full to partial sun is given in Table 1. This list is composed of reliable species that have performed well in research trials at the NH Agricultural Experiment Station in Durham and elsewhere around the state. Not every species will thrive (or even survive) on every site, but most are widely adaptable.

Seed mixes can be customized to meet your objectives and budget. The cost for the seed mix in Table 1 will run an average of $60-80 per 1000 square feet, if seeded at a rate of 20 lbs per acre (0.5 lbs/1000 square feet). If budget is not a limiting factor, you might want to add seeds of native lupine and butterfly weed, both of which require very dry soils. If your site tends to be wet, a more appropriate mix would contain cardinal flower, blue vervain, Culver’s root, golden Alexanders, boneset, swamp milkweed and Joe-Pye weed.

You can either purchase seed packets and mix the seed yourself, or a wildflower seed company may mix it for you on request. Order seed early in the summer to avoid shortages of popular mixes or species. Ask to have the (large and fluffy) native grass seed packaged separately from the (mostly tiny) wildflower seed. Store the wildflower seed in the refrigerator until planting time. The grass seed would ideally be refrigerated as well, but if there isn’t room for it, keep it in another cool dry place.

UNH custom mix of reliable species, suitable for sunny sites with medium to dry soils and a pH of 5.5 or above. Suggested seeding rate is 0.5 lbs per thousand square feet of area.

Wildflower Species, Common Names, Percent of mix by weight

- Aguilegia canadensis, Red Columbine, 3%

- Asclepias syriaca, Common Milkweed, 3%

- Chamaecrista fasciculata, Partridge Pea, 8%

- Coreopsis lanceolata, Lanceleaf Coreopsis, 3%

- Echinacea purpurea, Purple Coneflower, 7%

- Echinacea pallida, Pale Purple Coneflower, 11%

- Eutrochium purpureum,Purple Joe-Pye Weed, 1.5%

- Heliopsis helianthoides, Oxeye Sunflower, 2%

- Monarda fistulosa, Wild Bergamot, 0.50%

- Monarda punctata, Dotted Horsemint, 0.50%

- Oligoneuron rigidum, Stiff Goldenrod, 0.50%

- Penstemon digitalis, Foxglove Beardtongue, 1.

5%

5% - Ratibida pinnata, Yellow Coneflower, 3.5%

- Rudbeckia hirta, Black Eyed Susan, 2%

- Solidago speciosa, Showy Goldenrod, 1%

- Symphyotrichum novae-angliae, New England Aster, 1%

- Symphyotrichum laeve, Smooth Blue Aster, 2%

Grass Species, Common Names, Percent of mix by weight

- Elymus canadensis, Canada Wild Rye, 10%

- Shizachyrium scoparium, Little Bluestem, 30%

- Sorghastrum nutans, Indian Grass, 10%

Site Preparation

Successfully establishing a meadow from seed is a three-year process, with the first year devoted to good site preparation. This isn’t the fun part but eliminating competitive weeds before you plant is essential to long-term success. How to get started depends on the beginning site conditions and what materials and methods you decide to use. The following methods have been developed based on research and demonstration plantings in New Hampshire and are appropriate for the Northeast and other areas with similar climate patterns.

Smothering with black plastic excludes light from the underlying weeds, preventing photosynthesis which is essential for plants to survive over time. Although black plastic absorbs some heat during the day, soil temperatures underneath do not get high enough for long enough to kill weed seeds. Solarization, in contrast, acts by trapping solar radiation and converting it to heat underneath clear plastic sheeting. Extreme temperatures for long durations can reduce viability of sensitive weed seeds, although the results are inconsistent in our climate.

What are You Starting with?

Rough turf or lawn areas – It is essential to completely kill existing grasses and other perennial weeds in a turf area before planting wildflowers. A full season of site preparation is critical to success, because young wildflower seedlings stay small and low to the ground their first year of growth and are not able to compete against more vigorous weeds. Perennial grasses, such as our cool season lawn and pasture grasses, spread from strong underground roots and rhizomes and are especially troublesome when trying to establish wildflowers. These and other perennial weeds can be effectively killed by a process called “smothering” during the course of the summer prior to planting wildflower seeds. Steps to take:

These and other perennial weeds can be effectively killed by a process called “smothering” during the course of the summer prior to planting wildflower seeds. Steps to take:

- Mow the area as short as possible once or twice after it greens up in the spring. Scalp it! Then, rake off any excessive organic matter to create a smooth surface. Leaving a light layer of clippings is okay. Do not till the soil.

- Lay sheets of thick (4- or 6-mil) black plastic over the entire area, overlapping the edges by about a foot if you use more than one sheet or roll of plastic. Bury all the outside edges with soil, and/or hold the plastic down with rocks, cinderblocks, bricks or other available materials. The objective is to exclude light from the grass and weeds trying to grow under the plastic. Weeds without light are unable to photosynthesize and will eventually run out of energy and die. Any seeds that germinate under the plastic are likewise unable to survive for long.

Opaque tarps, landscape cloth, or thick layers of organic mulch can be used in place of black plastic if desired.

If you prefer to use an organic mulch, it’s best to start with a layer of cardboard so that grass and weeds cannot grow up through the mulching material. Watering the cardboard and pinning it down may help it stay in place. Applying shredded bark, leaves or other material over the top may make it less conspicuous than an expanse of plastic or cardboard. However, all the organic material should be raked off and redistributed elsewhere before seeding, to avoid enriching nutrient levels in the soil.

If you prefer to use an organic mulch, it’s best to start with a layer of cardboard so that grass and weeds cannot grow up through the mulching material. Watering the cardboard and pinning it down may help it stay in place. Applying shredded bark, leaves or other material over the top may make it less conspicuous than an expanse of plastic or cardboard. However, all the organic material should be raked off and redistributed elsewhere before seeding, to avoid enriching nutrient levels in the soil.

- Leave the soil covered from mid-June until mid-September. When you remove the plastic or other mulch materials, you will have bare soil on which to plant. Avoid disturbing this clean seed bed; do not till the prepared area or you may stimulate more weed growth. Do not apply compost, manure or other nitrogen-rich material, because wildflowers do best in soil that is low in nutrients. If needed, rake lightly to remove dead grasses and surface debris just before spreading the wildflower seed.

Smothering is an easy, inexpensive, no-till method for preparing small to medium size areas. Alternatively, in turf areas you could remove the top layer of sod with a sod cutter and then apply one of the site preparation methods described for cultivated soil, below

A clean seed bed is exposed when black plastic is removed in September, after being in place for several weeks.Overview of research trial comparing various methods of site preparation for killing existing vegetation before seeding a meadow mix.A buckwheat cover crop in front of a previously established meadow.Use herbicides with caution. Follow all label instructions including the use of protective clothing. Do not spray when weeds are in bloom or bees are present.

Cultivated soil (such as an agricultural field or garden) – A piece of land that has been recently cultivated for crops may appear to be relatively weed-free; however, there is usually a reserve bank of weed seeds lying dormant in the soil. Eliminating seedlings as they appear (and before they set seed) will diminish the weed seed bank over time.

Eliminating seedlings as they appear (and before they set seed) will diminish the weed seed bank over time.

Four options for reducing the weed seed bank are presented below. Any of these strategies should be implemented for the entire growing season prior to planting the meadow mix. The first two methods tend to be most effective for annuals and some perennials reproducing from seeds, but are less effective where perennial grasses are already well-established; if that is the case, use of herbicides or the smothering method described above is more effective.

- Repeated tillage or cultivation. If weed pressure is low, manually pulling or hoeing to kill germinating seedlings may be sufficient, but for large areas and/or heavy weed pressure, a mechanical cultivator is recommended. If perennial grasses or deep rooted weeds are present, the area should be tilled deeply first, then shallower cultivations used subsequently. Cultivating at a shallow depth should suppress germinating annuals and some broadleaf perennials but is less effective on clover and grasses, especially those coming back from root pieces or rhizomes.

Repeat the operation whenever a flush of weeds appears.

Repeat the operation whenever a flush of weeds appears. - Cover crops. Planting a dense summer cover crop will suppress weeds by shading and competing for space. Buckwheat is a good choice and will bloom and provide floral resources for bees during the summer. Mow or roll it at the end of the bloom period to prevent seed set; any live tissue remaining will be killed by freezing temperatures in fall. A late season crop of oats is also a good option, as oats will be killed by winter temperatures. Cover crop residue must decompose before seeding wildflowers, however, so fall planting is not feasible. Rake off debris and smooth the soil surface before seeding the following spring, but tilling is not recommended as it will bring up more weed seeds.

- Herbicides. Two or three applications (early season, mid-season and possibly early fall) of a nonselective systemic herbicide is a highly effective method for killing actively-growing annual and perennial weeds.

There are alternative “burn down” and/or organic products which may be used, but these are not translocated in the plant to kill roots and rhizomes; therefore, more applications are needed to eliminate weeds as regrowth occurs and/or new seeds germinate throughout the growing season. Do not till the soil after using herbicides in order to avoid bringing up more weed seeds.

There are alternative “burn down” and/or organic products which may be used, but these are not translocated in the plant to kill roots and rhizomes; therefore, more applications are needed to eliminate weeds as regrowth occurs and/or new seeds germinate throughout the growing season. Do not till the soil after using herbicides in order to avoid bringing up more weed seeds. - Solarization. This method involves covering bare, moist soil with clear (not white) plastic from mid-June through mid-September or longer. Effective solarization depends on trapping solar radiation as heat, raising the soil temperature high enough to kill weed seeds. Solarization is most reliable in hot, arid climates, but may yield some success if the site is fully exposed to sun and the edges of the plastic are buried to effectively trap heat. Use 4- or 6-mil UV resistant plastic, such as growers use to cover high tunnels or greenhouses. Used plastic is okay but will develop tears and holes more quickly from photo degradation or from animals such as deer walking across the surface.

Use heavy-duty clear repair tape to seal up any tears and holes which occur as soon as possible, or the openings will act as vents and make the solarization process less effective. There are conflicting reports on the effectiveness of soil solarization on weed suppression in northern climates and results may vary from year to year. In a cloudy, cool season it is apt to be unsatisfactory.

Use heavy-duty clear repair tape to seal up any tears and holes which occur as soon as possible, or the openings will act as vents and make the solarization process less effective. There are conflicting reports on the effectiveness of soil solarization on weed suppression in northern climates and results may vary from year to year. In a cloudy, cool season it is apt to be unsatisfactory.

Forest/woodland sites – recently logged or cleared woodlands usually have low soil pH and nutrient levels, but still can become successful meadow areas. Stumping, grading and/or excavating and raking is usually necessary. The period of time between clearing and seeding may be bridged with an annual grass crop or cover crops. Watch to see what weeds (or tree sprouts!) emerge during this time and use herbicides and/ or mechanical controls as needed. Cover crops which are winter killed, such as oats or buckwheat, will help smother new weeds that come up during the growing season, but essentially prevent fall planting, as they must first decompose or be removed. It is best not to till, in order to prevent new weed seeds from being brought to the surface, as well as rocks and roots.

It is best not to till, in order to prevent new weed seeds from being brought to the surface, as well as rocks and roots.

An effort should be made to select species that are tolerant of acid soils. However, if pH is very low (<5.5), it may be prudent to make an application of lime and other amendments as recommended by a soil test. Incorporation of amendments by tilling creates disturbance and may result in high subsequent weed pressure, but may be needed to improve growth on poor, acid sites. Tilling may bring up roots, rocks and other items, requiring more raking and smoothing before seeding.

Other disturbed sites – construction sites or other sites which have been excavated, graded and/or filled with soil from off-site present a special challenge because conditions are hard to predict. Gathering as much information as possible will help you select appropriate meadow species for planting. Have the soil tested for soil texture, pH, nutrient levels, and organic matter. Once the site work is done, observe water movement and do a percolation test to check drainage. Using all this information, select a mix of species most suitable for the conditions.

Once the site work is done, observe water movement and do a percolation test to check drainage. Using all this information, select a mix of species most suitable for the conditions.

To determine what the potential weed pressure is, observe what types of weeds come up over time. To expedite this process, you can fill several nursery pots (or other large containers with drainage holes) with soil and water them regularly to see what weeds emerge. Based on your observations, determine whether there is a significant weed bank, in which case you should proceed as if it was a previously vegetated area, or if weed competition is minimal and you can plant soon.

Planting – When and How

After a season of site preparation, you are ready to plant! Remove plastic or other mulch materials and rake off any loose tree roots, leaves, cover crop residues, etc. to prepare a clean seed bed. Fall is a good time to seed, as wildflower germination will be enhanced by exposure to cold temperatures and damp soil during the winter. The fall planting season in northern New England extends from late September through early December, depending on the year. A safe strategy is to aim for mid- to late-October, whereas November weather is unpredictable and snow could cover the ground at any time. If that happens, or if there are other reasons you choose to plant in the spring, store your seed in the refrigerator or other cold (35-40°F), dry place for the winter and then plant it as early in the spring as possible.

The fall planting season in northern New England extends from late September through early December, depending on the year. A safe strategy is to aim for mid- to late-October, whereas November weather is unpredictable and snow could cover the ground at any time. If that happens, or if there are other reasons you choose to plant in the spring, store your seed in the refrigerator or other cold (35-40°F), dry place for the winter and then plant it as early in the spring as possible.

Broadcasting (spreading seed by hand) is the preferred method for small areas. A carrier such as vermiculite or sand is needed to “bulk up” the volume of material to be distributed

You might want to practice distributing the moistened carrier without any seed at first, to practice getting the right amount evenly distributed over the desired area. Use a broad sweeping throw for each handful, much like feeding the chickens.

When it’s time to plant, measure the area to be planted and perhaps divide it into smaller subplots of 400-500 square feet each to make seed distribution more precise. Calculate the amount of each type of seed (grasses and wildflowers) you need for each subplot and set it aside.

Calculate the amount of each type of seed (grasses and wildflowers) you need for each subplot and set it aside.

Mix the seed with vermiculite or other carrier for one subplot at a time in a plastic paint bucket or similar container. Start with the dry carrier then add small amounts of water at a time, stirring until it is slightly damp but not wet. Now you can mix in your seeds; the small seeds will stick to the carrier particles, keeping everything well-mixed for distribution. Add the wildflower seeds first, then the grass seeds, adding more water or vermiculite if needed. The precise amount isn’t important, but using 0.5 to 1 gallon of the carrier per 500 square feet area is adequate. Wearing latex gloves will keep the seed from sticking to your hands.

For each subplot, apply half the amount of seed while walking back and forth in one direction, then repeat in the other direction, as shown in the diagram below. Using a light-colored carrier such as vermiculite allows you to see how evenly you have distributed the mix on the soil surface. Scatter any remaining seed where needed.

Scatter any remaining seed where needed.

Raking lightly with a metal lawn or leaf rake after broadcasting helps work the seeds into the soil, but rake only ¼” deep so you do not bury the tiny wildflower seeds. If the soil is firm and level, skip raking and go straight to rolling the area with a lawn roller, or a cultipacker, which will press the seed into the soil. Good seed to soil contact is essential for holding the seed in place over the winter and helps keep the seedlings from drying out once they germinate in the spring. And finally, a thin layer of clean straw (one bale per 1000 square feet) distributed lightly over the top helps keep the seed in place.

And finally, a thin layer of clean straw (one bale per 1000 square feet) distributed lightly over the top helps keep the seed in place.

If seeding a large area (of several thousand square feet), you might want to try a mechanical seeder. A slitseeder or seed drill can be used on smooth level sites, such as an agricultural field, but most people don’t have access to that equipment, which may also be difficult to calibrate. A whirlybird-type broadcast lawn seeder or chest-carried crank seeder may work satisfactorily, but it is hard to keep the seed well-mixed and feeding properly; the tiny wildflower seeds tend to fall to the bottom and get used up first. Calibrate your seeder with a dry carrier (such as sand or rice hulls) before mixing in any seed. Then mix small batches of seed with the carrier, use half the amount going back and forth in one direction, then repeat in a perpendicular direction. In this case, do not add water to moisten the carrier, as it will prevent it from feeding through properly.

What to Expect

Year 1 - is the season for site preparation, an essential but not very attractive process. Time and effort spent this year will provide a clean seedbed to be planted and mulched in the fall or following spring. Skipping the site preparation process is sure to result in failure over the long run.

Year 2 – you will most likely be disappointed in how your meadow area looks the first season after planting. Patience is the key this year. You should see wildflower seedlings germinate and emerge as the soil warms up in the spring, but it’s hard to tell the wildflowers from the weeds at this point. Some wildflowers won’t even germinate for 2-3 years following planting, and most grow low to the ground the first season. If you haven’t done a great job of preparing the site and killing existing vegetation, weeds will grow up quickly and can easily smother or shade out the wildflowers. Hand-weeding may disturb germinating wildflower seedlings, so is not recommended. Consider mowing in mid-summer at a 4-6” mowing height, whacking the weeds back but going right over the top of most wildflower seedlings. Few wildflowers will bloom this year anyway, as they are devoting their energy to growing strong roots and shoots rather than flowers and seeds. Black-eyed Susan is the exception to the rule, so be sure to include it in your seed mix to provide cheerful yellow flowers this year. It will even recover and re-bloom after that mid-summer mowing.

Some wildflowers won’t even germinate for 2-3 years following planting, and most grow low to the ground the first season. If you haven’t done a great job of preparing the site and killing existing vegetation, weeds will grow up quickly and can easily smother or shade out the wildflowers. Hand-weeding may disturb germinating wildflower seedlings, so is not recommended. Consider mowing in mid-summer at a 4-6” mowing height, whacking the weeds back but going right over the top of most wildflower seedlings. Few wildflowers will bloom this year anyway, as they are devoting their energy to growing strong roots and shoots rather than flowers and seeds. Black-eyed Susan is the exception to the rule, so be sure to include it in your seed mix to provide cheerful yellow flowers this year. It will even recover and re-bloom after that mid-summer mowing.

Crabgrass is a special challenge on some sites. A thick blanket of crabgrass can smother out germinating wildflowers, and is not sufficiently managed by mowing. There are few options for controlling crabgrass other than use of a post-emergent selective grass herbicides that can be sprayed over-the-top of wildflowers. One application to actively growing crabgrass before it goes to seed will effectively kill it, reopening the area to allow light to reach the underlying wildflowers. As with all herbicides and other pesticides, follow label directions carefully, and consider whether hiring a licensed applicator is required or prudent for the situation at hand.

There are few options for controlling crabgrass other than use of a post-emergent selective grass herbicides that can be sprayed over-the-top of wildflowers. One application to actively growing crabgrass before it goes to seed will effectively kill it, reopening the area to allow light to reach the underlying wildflowers. As with all herbicides and other pesticides, follow label directions carefully, and consider whether hiring a licensed applicator is required or prudent for the situation at hand.

Year 3 – If they survived last year, the wildflowers will emerge quickly in the spring and grow much faster and larger this year. Most weeds are slower to get started and pose much less of a problem this year, often being out-shaded and out-competed by a dense wildflower mix. By late June, you should see some flowers on coreopsis and columbine, if they are in your mix, followed by foxglove beardtongue and blackeyed Susan. In mid-summer, wild bergamot (bee balm) and oxeye sunflowers will bloom prolifically, and perhaps a few yellow and purple coneflowers will appear. Wild Rye shoots up and provides a pleasant contrast with its distinctive seed heads. Other warm-season grasses may still be slow and inconspicuous.

Wild Rye shoots up and provides a pleasant contrast with its distinctive seed heads. Other warm-season grasses may still be slow and inconspicuous.

Year 4 and beyond – You and the bees will reap the rewards of your efforts, enjoying a dense, diverse mix of colorful wildflowers from spring through late fall, when goldenrods and asters provide a fall feast for bees. Black-eyed Susan, coreopsis and a few others will diminish in numbers and tend to migrate to the edges of your meadow. The mid-summer meadow buzzes with bees and other insect pollinators, and birds reap the benefit of bugs and seeds to eat. Milkweed finds its place in the meadow, and monarchs feast on the nectar of many meadow flowers before laying their eggs on the undersides of milkweed leaves. Warm-season grasses fill in areas where the wildflowers are less dense, providing clumps that shelter ground-nesting bees and other creatures.

These photos show the growth and development of the same meadow planting over time.

First year after planting (mid-June).First year after planting (mid-August).Second year after planting (mid-June).Second year after planting (early August).Third year after planting (early June).Third year after planting (early August).Third year after planting (late September).A meadow does not need a dormant season mowing every year, just often enough to keep shrubs and trees from growing up.

Long Term Changes and Maintenance

Once you have an established meadow, there is little you need to do. Monitor for tall and aggressive weeds such as sumac, pokeberry, purple loosestrife and bittersweet vine, removing them by hand in the fall when you can pull or wrench the roots out. Try not to disturb the soil any more than necessary in the process, because disturbance creates openings for future weeds and invasives. You can continue to edit the meadow by adding plants to sparse areas and preventing some of our volunteer wildflowers (a.k.a. weeds) from taking over. Some to watch for include daisy fleabane, evening primrose and common mullein. These are all good pollinator plants but may outcompete some of the more desirable species you planted, reducing diversity. Cutting them back before they set seed will help keep them in check.

These are all good pollinator plants but may outcompete some of the more desirable species you planted, reducing diversity. Cutting them back before they set seed will help keep them in check.

Once the meadow is finished flowering and freezes kill the last of the asters to the ground, consider the beauty in the structure and golden colors of standing seed heads and grasses, which the birds will appreciate well into the winter. If you need to tidy up, mow the meadow down in November or leave it stand until early spring. Mow high (6-8” or higher) and wildlife will continue to nest and forage in the meadow through the winter and spring. Mowing every year is not required; its primary purpose is to discourage woody shrubs and trees from taking over. If you have a large meadow area, consider mowing only one-third or one-quarter of it each year, leaving the rest for winter habitat.

The meadow is an ever-changing landscape. Weather variations, soil conditions, and wildlife will determine which wildflowers and grasses become dominant and which fade away over time. In a wet year, plants like Joe Pye-weed and cardinal flower may flourish, while in a dry year bergamot and coneflowers may abound. Take a step back and enjoy the changes – a meadow is a process, not a product!

In a wet year, plants like Joe Pye-weed and cardinal flower may flourish, while in a dry year bergamot and coneflowers may abound. Take a step back and enjoy the changes – a meadow is a process, not a product!

The meadow in winter.

1 Seed Sources for New England Meadows. UNH Extension, 2018. https://extension.unh.edu/blog/seed-sources-new-england-meadows

Learn more about wildflowers meadows, pollinator habitat and soil testing.

Acknowledgements: This work was funded by the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture Hatch Multistate Project 1010449, with additional support from the Anna and Raymond Tuttle Environmental Horticulture Fund and the NH Horticultural Endowment. The author gratefully thanks Amy Papineau, Sean Fogarty, Sam MacNeil and the farm crew at the AES Woodman Horticulture Farm for all their help.

How to Grow a Wildflower Meadow - Lawn Care Blog

Feeling uninspired by your traditional grass lawn? Consider creating a vibrant, eco-friendly wildlife haven instead. If you want to sprinkle color throughout your yard and want to bring beautiful butterflies, bees, and birds fluttering into your space, look no further than a native wildflower meadow.

If you want to sprinkle color throughout your yard and want to bring beautiful butterflies, bees, and birds fluttering into your space, look no further than a native wildflower meadow.

Here’s how to grow your own low-maintenance meadow from scratch.

In this article we’ll cover:

What is a wildflower meadow?

A wildflower meadow is a garden made up of native flowers, plants, and grasses that grow well together. It’s a specifically designed community of diverse plant species — annuals, biennials, and perennials — that thrive in your region and growing conditions.

When it comes to increasing plant biodiversity, wildflower meadows are a dream. Plus, they’re the perfect home for pollinators, small mammals, and beneficial insects facing habitat loss.

Wildflower meadows reduce erosion on slopes, decrease harmful runoff, and won’t require harsh synthetic herbicides and fertilizers. They’re an eco-friendly grass alternative that will give you a colorful show right outside your window.

Where can I grow a wildflower meadow?

Wildflowers grow all across the country, but they tend to do best in open areas with full to partial sun and little to no foot traffic.

Choose a site that:

- Gets at least six hours of direct sunlight

- Has uncompacted, well-draining soil

- Does not have a persistent weed problem

- Has space (at least 400 square feet) for a variety of plants

- Is far from pesticides and household chemicals that could harm bees

Wildflowers blend well with natural or semi-natural locations:

- Adjoining a forest or woodlot

- Bordering your lawn or patio

- Next to a fence or property line

- In the corner of your yard (if there is sufficient light)

Pro Tip: While your soil must drain well, it doesn’t have to be nutrient-rich. Most wildflowers prefer nutrient-poor soils, so don’t add compost or fertilizer to your meadow.

When to plant a wildflower meadow

If you live in the cooler, upper half of the U. S., plant your wildflower meadow in mid- to late spring, after the last frost date has passed and soil has warmed up to at least 55 degrees Fahrenheit.

S., plant your wildflower meadow in mid- to late spring, after the last frost date has passed and soil has warmed up to at least 55 degrees Fahrenheit.

If you live in the warmer, lower half of the U.S., plant your wildflower meadow in late fall or early spring. If you have mild winters, planting in fall is best: It gives your seeds the chance to germinate and establish a strong root system before going dormant in winter. In spring, they’ll be healthy and ready to grow.

What you need to plant a wildflower meadow

- Wildflower seeds

- Fine sand

- Sod cutter (if removing grass by cutting)

- Black plastic sheeting (if removing grass by smothering)

- Rototiller or hoe (optional)

- Herbicide (optional)

- Metal or leaf rake

- Lawn roller or cultipacker (optional)

- Straw mulch

6 steps to plant a wildflower meadow

1. Remove existing grass

Wildflowers don’t compete well with turfgrasses, so all existing vegetation must be removed before seeding. There are two methods to remove grass for a successful start to your meadow: smother grass with black plastic or use a sod cutter.

There are two methods to remove grass for a successful start to your meadow: smother grass with black plastic or use a sod cutter.

Deciding between the two is a trade-off between time and labor. It takes two to three months to smother grass, but once it’s smothered, you won’t have to do any additional tilling (and you can skip to Step 3). Cutting sod is an afternoon task, but you’ll have to till your soil afterward.

Smother grass with black plastic

A sheet of black plastic deprives grass and weeds of the light they need to photosynthesize. It’s one of the most popular, inexpensive methods of getting rid of an existing lawn.

Start by mowing your lawn once or twice on the lowest setting, scalping the grass. Rake up debris and grass clippings. Then, lay a sheet of thick, black plastic over your area, overlapping the edge of your plastic so that no light can filter through. Place soil, rocks, or bricks around the edges of the sheeting to hold it firmly in place.

Keep your soil covered for two to three months. If you’re planting in fall, lay the black plastic in mid-June and remove it in mid-September. Once you have removed the black plastic, gently rake away organic matter and debris. You’re ready for planting!

Pro Tip: Before applying black plastic sheeting, it’s a good idea to aerate your lawn to get soil nutrients flowing for your new wildflowers.

Use a sod cutter

Start by scalping your lawn and raking up debris just like you would if you were going to smother your grass. Then, use a sod cutter (you can rent a motorized one for large areas) to remove the surface layer of your lawn. Set the blade depth to half an inch.

If using a sod cutter, you’ll also need to till your area and possibly apply weed killer.

2.

Weed your area (if you used a sod cutter)Don’t let bare soil trick you into thinking your lawn is weed-free. Weed seeds are buried under the surface, ready to sneak up on your wildflowers. Protect your meadow from weedy intruders by either tilling or both tilling and applying herbicide.

Protect your meadow from weedy intruders by either tilling or both tilling and applying herbicide.

Till your soil

Till the soil deeply with a rototiller (or a hoe for smaller areas) six to eight weeks prior to planting. This will dislodge deep-rooted weeds and grasses. Then, repeat the tilling process at a shallower depth every two to three weeks to eliminate persistent old weeds and fresh new weeds.

While tilling is a wonderfully chemical-free method of weed removal, you may need a more intense approach if perennial weeds are putting up a fight.

Apply herbicide

Perform the same tilling process as above six weeks before planting. Rake the soil and wait three weeks for weeds to grow back. Then, attack them with a non-selective spray herbicide that has a short residual period. This will quickly kill weeds without sticking around to harm your fresh seeds.

Remove the dead weeds before planting your fresh seeds.

Pro Tip: To prevent new weed growth, do not till the soil after applying herbicide.

3.

Scatter seedsIt’s time to let your wildflowers loose! Scatter your seed on a windless day so your seeds germinate in the right place.

Calculate how much seed you need based on the area of your seedbed: The suggested seeding rate for most wildflowers is ½ pound of seed per 1,000 square feet, or 80 seeds per square foot. So, if you want a 2,000-square-foot wildflower garden, you’ll need one pound of seed.

Mix seeds with fine sand in a proportion of one part seeds, four parts sand. Sand helps you spread seeds more evenly, and since it’s lighter in color than seed, you can still see how seeds are dispersed over your lawn.

Scatter your seeds by hand using a continuous sweeping motion. Start with half of your sand and seed mixture. Walk back and forth in one direction (north to south) over your lawn, spreading seeds.

Then, grab the other half of your sand and seed mixture and walk back and forth in the other direction (east to west). When you’re done, your lawn will look like a seed checkerboard.

When you’re done, your lawn will look like a seed checkerboard.

4.

Compress seedsAfter scattering your seeds, rake lightly (just ¼ inch deep), so that seeds have good contact with the soil but are not buried.

Once your lawn is evenly raked, tamp down your seeds either with your feet or with a lawn roller or rented cultipacker (a heavy-duty roller designed to firm up large seedbeds). Add a light layer of straw mulch to protect the seeds. Straw is especially helpful in preventing erosion if you are planting wildflowers on a slope.

5.

WaterKeep soil moist for the first four weeks after planting (until wildflower seedlings are 4-6 inches tall) to ensure successful germination.

6.

MaintainMowing: To promote fresh growth in the spring, mow your wildflower meadow in late fall (the first fall after you plant it), after most of your flowers have dropped their seeds. Mow on your highest mower setting (4 inches or more). This will remove dead flower heads so your wildflowers can focus their energy on growing new flowers the following spring. Leave the flower clippings on your lawn for natural reseeding.

This will remove dead flower heads so your wildflowers can focus their energy on growing new flowers the following spring. Leave the flower clippings on your lawn for natural reseeding.

Weeding: Herbicides can damage or kill wildflowers, so when weeds pop up, you’ll have to cut them with scissors or shears, weed them by hand, or spot spray them. Cutting weeds with scissors or small shears is the best practice, as it won’t damage surrounding plants or roots. Just snip their stems at the soil surface every other week.

Watering: As wildflowers mature, their roots grow longer and stronger and they require less water. You’ll need to give your water 1 inch of water weekly for the first year, but you may be able to water less frequently in the second year. By the third year, your meadow will be largely self-sufficient. It will only need watering during especially dry periods.

Pro Tip: Never mow tall grasses in your meadow at a blade setting below 6 inches, as this can damage or kill them.

Types of plants for your wildflower meadow

The best types of native flowers for your meadow depend on your specific growing region, but check out these popular flowers to attract a garden full of fluttering friends.

10 popular wildflowers for butterflies and bees

- Black-eyed Susan

- Common madia (tarweed)

- Arroyo lupine

- Purple coneflower

- Gum plant

- Goldenrod

- Aster

- Milkweed

- Yarrow

- Golden Alexander

If you’d rather not buy a bunch of individual seed packets, you can find a gold mine of wildflower seed mixes at your local gardening center. There are wildflower mixes for all different growing conditions and soil types, so you can choose which blend best suits your lawn.

Best grasses to suppress weeds

Think that a wildflower meadow is mainly made up of, well, wildflowers? Think again. For optimal growth, prairie managers recommend that native grasses make up 50%-80% of your meadow.

- If you live in a cooler climate (in the upper half of the U.S.) or in the Transition Zone, consider planting hard fescue, sheep fescue, Canada wild rye, or little bluestem to prevent weed growth.

- If you live in a warmer climate (in the lower half of the U.S.), go with buffalograss, sideoats grama, blue grama, Lindheimer’s muhly, or big bluestem. These grasses won’t compete with your wildflowers, but they will stop weeds from rearing their heads.

- Avoid Kentucky bluegrass, bermudagrass, and annual ryegrass. Aggressive growers can crowd out your flowers.

Pros and cons of a wildflower meadow

Before you commit to a wildflower meadow, consider the benefits and disadvantages of a wildflower-filled yard.

Pros of a wildflower meadow:

✓ Great for pollinators

✓ Promotes biodiversity

✓ Adds natural color and texture to your landscape

✓ Reduces erosion and runoff pollution

✓ Grows in poor soil

✓ Little to no harsh chemicals required

✓ Improves soil health

✓ Low-maintenance

Cons of a wildflower meadow:

✗ Takes time for plants to flower and grow strong

✗ Cannot tolerate heavy foot traffic

✗ Looks less tidy than a traditional lawn

✗ Most wildflowers need full to partial sun

✗ Not a good play area for children and pets

✗ Requires a large lawn space

✗ Susceptible to weeds

FAQ about wildflower meadows

1. Can I speed up the growing process so my flowers bloom sooner?

Can I speed up the growing process so my flowers bloom sooner?

Yes! You can plant a combination of seeds and container-grown plants to speed up the maturation process. Buy containers of slow-growing perennial wildflowers to give them a head start in the growing and blooming process.

Plant your container-grown flowers before seeding so they don’t disturb the soil while seeds are germinating.

2. What happens if crabgrass invades my wildflower meadow?

If crabgrass starts to smother your wildflowers, you may need to apply a post-emergent selective herbicide. One spray application to growing crabgrass (before it goes to seed) will kill it. In general, though, herbicide should be avoided, as it can stress or kill wildflowers.

3. What can I do during the second year to make sure my meadow survives into year three?

Weed invasions and bare spots are major hurdles in the second growing season, so give your garden some extra TLC.

—Clip weeds weekly as they sprout. Avoid hand weeding and chemical sprays when possible. —Reseed or spot transplant in bare areas to ensure even distribution of wildflowers.

—Water about 1 inch per week. Your plant roots aren’t fully mature yet.

4. What types of wildflowers can I grow in a drought-prone lawn?

Living in an arid region doesn’t destroy your wildflower options. Popular drought-tolerant and drought-resistant wildflowers include:

—Zinnia (Zinnia elegans): USDA zones 2-11

—Blue flax (Linum perenne) : USDA zones 3-8

—California poppy (Eschscholzia californica): USDA zones 6-10

—Common milkweed (Asclepias syriaca): USDA zones 3-9

—Common yarrow (Achillea millefolium): USDA zones 4-8

—Gumweed: (Grindelia camporum): USDA zones 7-9

To find wildflowers perfect for your specific region, check out the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center’s guide to regional wildflowers.

Going wild for wildflowers

A wildflower meadow takes time to mature, but it’ll make a stunning debut in its third year. Perennial flowers will finally bloom, giving your yard gorgeous new color, and native plants will grow more densely, naturally crowding out weeds. You can sit back, relax, and enjoy the beautiful butterfly show.

Want the butterflies without the strenuous weeding and seeding? Contact a local lawn care company to transform drab grass into a magical meadow.

Main Photo Credit: JillWellington | Pixabay

Total

11

Shares

Maille Smith

Maille-Rose Smith is a freelance writer and actor based in New York. She graduated from the University of Virginia. She enjoys watching theatre, reading mysteries, and listening to psychology podcasts. She is an orchid enthusiast and always has a basil plant growing in her kitchen.

Posts by Maille Smith

yellow, white, purple, blue, etc.

Field and meadow herbs and flowers create incredibly picturesque compositions in their natural environment. The variety of plants, flowers, shapes, aromas impresses and fascinates with its beauty. A characteristic feature of such crops: they are extremely unpretentious in care and undemanding to growing conditions, with the possible exception of lighting. For this reason, you can grow them on your site very easily and not difficult. Many of these flower crops can be used for a variety of landscape design solutions. For example, to create beautiful ornamental meadows, Moorish lawns, fragrant flower beds in your garden.

Content

- 1 Catalog of field and meadow colors with photos and names

- 1.1 Yellow wildflowers

- 1.2 White wildflowers

- 1.3 Blue meadow flowers

- 1.4 field plants with purple and siren flowers 9000 and red meadow flowers

Flower crops growing in fields and meadows in the wild, a great variety! And each of these plants has some attractive differences. Let's look at the popular, interesting and beautiful wild, meadow flowers. Next, a catalog of flowers with photos and names will be waiting for you.

Let's look at the popular, interesting and beautiful wild, meadow flowers. Next, a catalog of flowers with photos and names will be waiting for you.

Wildflower yellow

Yellow is a charming, cheerful color that is associated with the sun, summer. With the help of plants with yellow flowers, you can create colorful, vibrant flower beds and set accents.

Goose onion (bird onion)

Devasil

Donnik (Burkun)

9000 9000

Kupalan.0003

White floor White flowers

White symbolizes tenderness, purity. In the field, in the meadow and in the backyard, plants with white flowers give the space airiness, veil, solemnity.

Anis (Anise Bednets)

Forest windmill (forest anemone)

Crocus (Shafran)

Crocus flowers can be painted in white, purple, blue, yellow.

Aquilegia (Catchment)

Aquilegia can be not only blue and light blue, but also pink, white, purple.

Jungar aconite

Another name for the Jungar aconite "Dzhungar wrestler".

Vasilek

Veronika Dubravnaya

Lugovaya General (Lugovoi Mrankshael)

bitter0003

AISTRIT (Robbeytnik)

ALTEY Medicinal (ALTEY Pharmacy)

Valerian medicinal (Koshachy grass)

9000 9000 9000 9000

(Large serpentine)

This field plant boasts a variety of names: Serpentine knotweed, Large serpentine, Crayfish necks, Snake root, Turtleneck.

Red clover (or red)

Field poppy (Seed poppy)

Field and meadow flowers are certainly beautiful and charming. But they can boast not only of their charming appearance. Also, many of them are honey plants, that is, they are able to attract beneficial pollinating insects (bees, bumblebees) to the garden. In addition, such cultures are used in pharmacology and traditional medicine for the treatment and prevention of certain diseases. They are also suitable for making charming and beautiful bouquets.

But they can boast not only of their charming appearance. Also, many of them are honey plants, that is, they are able to attract beneficial pollinating insects (bees, bumblebees) to the garden. In addition, such cultures are used in pharmacology and traditional medicine for the treatment and prevention of certain diseases. They are also suitable for making charming and beautiful bouquets.

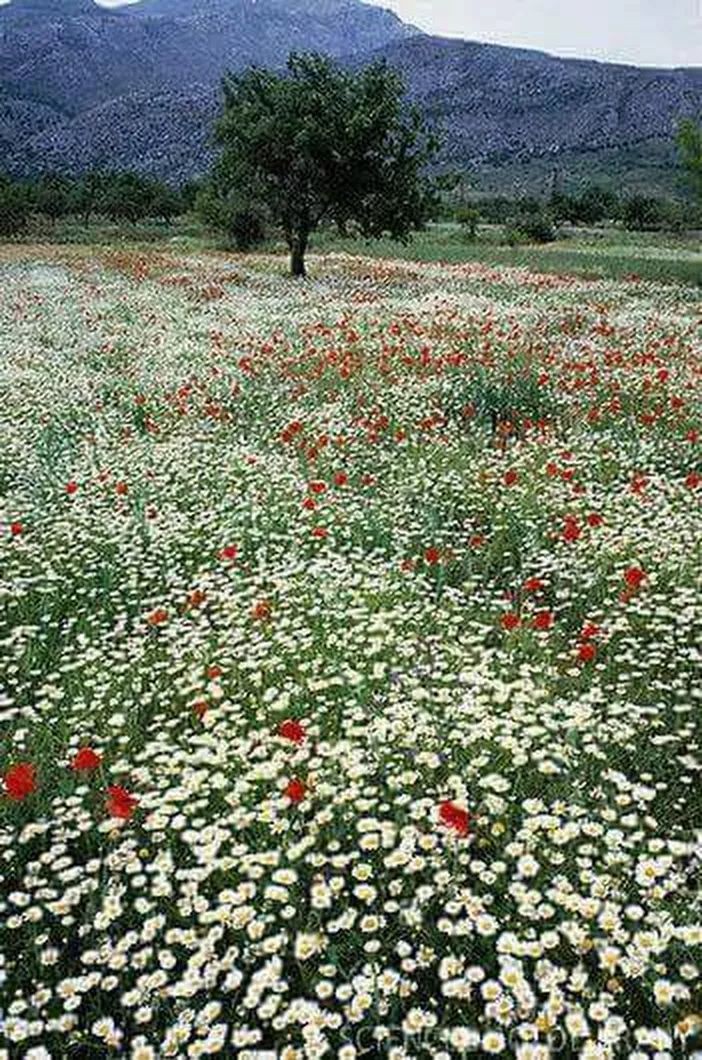

Meadow and wild flowers: photos and names of plants

In the minds of most people, meadow and wild flowers are associated with the vast expanse of an emerald green field, and on it expressive bursts of white, blue, yellow, pink, red natural flowers. Kingdom of herbs and colors! In the same way, touchingly tender wildflowers are suitable for creating decorative meadow and Moorish lawns: being a successful addition to greenery, they at the same time know how to express themselves in the highest degree brightly and unforgettably. In addition to lawns on personal plots, simple meadow flowers can be perfectly used as a kind of herbal “framework” and a beautiful backdrop for country features and ideas. In addition, all this splendor has no equal in cultivation and care, since simple meadow and field plants are extremely undemanding in nature.

In addition, all this splendor has no equal in cultivation and care, since simple meadow and field plants are extremely undemanding in nature.

Well, then you can visually get acquainted with the most popular and common field and meadow plants.

Contents

- 1 Benefits of field and meadow plants and flowers for human health

- 2 The most popular meadow flowers and wild plants: names and photos

Benefits of field and meadow plants and flowers for human health Many of the meadow flowers and plants are medicinal herbs that you can collect and then make healthy decoctions and teas at home.

For example, in folk medicine, cornflower blue flowers are used as an antipyretic, as well as for diseases of the kidneys, bladder and as lotions for eye diseases.

Oregano vulgaris is able to have a calming effect on the central nervous system, increase the secretions of the digestive, bronchial and sweat glands, increase intestinal motility and have some analgesic and deodorizing effect.

Learn more

- Sweet pea monty don

- Top blenders on the market

- Around tree planter

- Cost for 10x10 deck

- Cool garden rooms

- Island cabinet ideas

- Should you trim hydrangeas

- Cool basement ideas for teenagers

- Can you plant seeds from a lemon

- Tips on closet organization

- Country yard designs