Grand houses in england

magnificent manor houses & mansions

Blenheim Palace. Credit: PixabayWe’ve toured the British Isles to bring you 25 of Britain’s best stately homes, from the World Heritage Site of Blenheim Palace to the ‘real’ Downton Abbey, Highclere Castle…

The number of heritage buildings still standing proudly across our land never fails to amaze us. Most of Britain’s best stately homes have hosted kings and queens, prime ministers, actors and poets – all manner of illustrious guests.

Here are some of Britain’s best stately homes, from examples of architectural brilliance to places that hide unbelievable stories. So read on, enjoy, and start planning your next trip.

1. Blenheim Palace, Oxfordshire

When listing Britain’s best stately homes, we simply had to mention Blenheim, the sprawling Oxfordshire estate that was built for John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough. The palace was built on land gifted to Churchill by Queen Anne. Anne also awarded him £240,000 for his victory over the French in the War of the Spanish Succession.

It was at Blenheim almost two centuries later that one of the duke’s descendants, Sir Winston Churchill, was born. The future prime minister even chose to propose to Clementine Hozier here, by the Temple of Diana, in 1908.

The house – the only non-royal or non-episcopal country house in England to be called a palace – is a masterpiece of English Baroque architecture. Designed by Sir John Vanbrugh and Nicholas Hawksmoor, it includes many beautiful features, such as the painted ceiling in the Saloon.

However, Blenheim’s 2,000 acres of gardens – one of the most exquisite works of 18th-century landscape architect Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown – are what really make it special. It’s small wonder UNESCO declared it a World Heritage Site in 1987.

2. Highclere Castle, West Berkshire

Highclere Castle is the ‘real’ Downton AbbeyWith the Downton Abbey film recently gracing our screens, surely it’s time to revisit the glorious Berkshire ancestral home that has formed the backdrop to so many scenes of the Crawley family and their household.

Certainly one of Britain’s best stately homes, The ‘real’ Downton Abbey, Highclere Castle, is the family seat of the Earls of Carnarvon. It was the current countess, Lady Carnarvon, a close friend of Downton Abbey writer Julian Fellowes, who saw the value in opening the house up to the period drama that has revived the estate’s fortunes.

Although Highclere has been in the hands of the Carnarvon family since 1679, (and its gardens were also designed by Capability Brown), the current house was remodelled in the Jacobean style in 1838 for the 3rd Earl of Carnarvon by Sir Charles Barry, the man who famously rebuilt the Palace of Westminster.

Highclere Castle became the focus of a media circus in 1922 when the 5th Earl discovered the Tomb of Tutankhamun. The earl died shortly after the discovery, leading to the story of the ‘Curse of Tutankhamun’. However the earl’s death could be explained by blood poisoning from an infected mosquito bite.

3. Chatsworth, Derbyshire

The state apartments of Chatsworth House are extraordinary. Credit: Paul Barker

Credit: Paul BarkerFew English estates draw such delight as this one in the heart of the Peak District. Chatsworth is known to many as Pemberley in the 2005 film adaptation of Pride and Prejudice, starring Keira Knightley. Eagle-eyed viewers may also remember it from another Knightley film, The Duchess.

Chatsworth has been the seat of the Dukes of Devonshire since 1549 and has passed through the hands of 16 generations of the Cavendish family.

The house is famed for its art collection, which spans four centuries, but its state apartments, overhauled to accommodate a visit from King William III and Queen Mary II that never actually happened, are extraordinary.

4. Hardwick Hall, Derbyshire

Hardwick Hall, more glass than wall. Credit: Eleanor Scriven/Robert Harding World Imagery/CorbisBess of Hardwick was one of the most influential figures in Elizabethan times – she was second in wealth only to Queen Elizabeth I – and Hardwick Hall was one of her homes.

It is a magnificent example of a prodigy house – showy properties built to house the queen on her annual progresses.

The plentiful windows – an extravagance as glass was expensive – led to the rhyme, ‘Hardwick Hall, more glass than wall.’

5. Wentworth Woodhouse, South Yorkshire

The East Front of Wentworth Woodhouse, the longest country house frontage in England. Credit: Leo RosserAlamyThe largest private residence in Europe, Wentworth is twice the width of Buckingham Palace. This 18th-century mansion has recently been bought and will undergo £40m of restoration work over the next 20 years.

It was once the home of Charles I’s ill-fated administrator, Thomas Wentworth, 1st Earl of Strafford. Wentworth was tried and beheaded for treason in 1641. The house also hosted a visit by King George V and Queen Mary in 1912.

6. Lacock Abbey, Wiltshire

The Cloisters at Lacock Abbey, Wiltshire. Credit: National Trust Images/Mark BoltonThis quirky country house, near the historic town of Lacock, was built on a former nunnery and represented the ‘real’ Wolf Hall, the family seat of the Seymours, in the recent TV adaptation of Hilary Mantel’s novels.

Scenes depicting King Henry VIII’s bedroom and his lodgings at Calais were also filmed here. In real life, Henry sold Lacock to one of his courtiers, Sir William Sharington, following the Dissolution of the Monasteries. It is now in the care of the National Trust.

7. Stonor, Oxfordshire

Edmund Campion printed his famous Decem Rationes at StonorAlthough it is one of our oldest manor houses, Stonor is also one of our lesser-known stately homes, despite the fact that one of the most significant religious events in British history took place here.

In 1581 Edmund Campion hid in the roof space while he printed 400 copies of his famous treatise, Decem Rationes, arguing for Catholicism. However, he was soon caught and tortured before being hung, drawn and quartered.

The house is open at select times from April to September and holds a rare copy of the Decem Rationes.

8. Castle Howard, North Yorkshire

It took over 100 years to build Yorkshire’s castle HowardSo ambitious was the vision for Castle Howard, the private residence of the Howard family for more than 300 years, that the Baroque building took over 100 years to complete. The result was astounding, though, with two symmetrical wings and a central dome.

The result was astounding, though, with two symmetrical wings and a central dome.

Although much of Castle Howard was devastated by fire in the 1940s, over the years many rooms have been restored. However, when the house was used as the backdrop for the film version of Evelyn Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited in 2008, parts were superficially restored and the East Wing remains a shell.

9. Crag Hall, Derbyshire

You can hire out the whole of Crag HallUntil recently this sandstone Georgian country house with views over Peak District National Park was the private shooting lodge and holiday home of the Earl and Countess of Derby, but now you can hire it for your own gathering.

Located amid historic royal hunting ground, this 12-bedroomed property can accommodate up to 21 guests. A perfect set-up for living out your Downton Abbey fantasies.

10. Kenwood House, London

The newly restored library at Kenwood House. Credit: English Heritage/Patricia PayneHidden in London’s Hampstead Heath, Kenwood House is a Robert Adam’s house, remodelled by the architect in 1764 to include a new entrance, attic-storey bedrooms and one of his most famous interiors – the Great Library, which was restored to its original colours during a major restoration project in 2013.

The grounds are home to ancient woodland and landscaped gardens, probably designed by Humphry Repton, and feature sculptures from the likes of Barbara Hepworth and Henry Moore.

11. Lyme Park, Cheshire

The Dining Room at Lyme Park. Credit: National Trust Images/Andreas von EinsiedelBest known for its starring role as Mr Darcy’s Pemberley in the 1995 BBC adaptation of Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice (yes, that scene when Colin Firth emerges from the lake), Lyme Park is a fine example of an Italianate palace.

Outside, the 1,300 acres are home to a medieval herd of red and fallow deer, while inside you’ll find an incredible collection of English clocks and the famous Mortlake tapestries. The Edwardian era was when Lyme Park was in its heyday and the house is a time capsule of that period.

12. Buscot Park, Oxfordshire

Buscot Park is home to the impressive paintings of the Farringdon Collection. Credit: The National Trust Photolibrary/AlamyThis stately home was built in the Renaissance Revival style of architecture between 1779 and 1783 for Edward Loveden Townsend. Buscot also houses the Farringdon Collection, with paintings by Rembrandt, Reynolds, Rubens and Van Dyck.

Buscot also houses the Farringdon Collection, with paintings by Rembrandt, Reynolds, Rubens and Van Dyck.

13. Great Chalfield Manor and Garden, Wiltshire

15th-century Great Chalfield Manor, Wiltshire. Credit: National Trust Images/Andrew ButlerThe stand-in for Thomas Cromwell’s home of Austin Friars in TV’s Wolf Hall, Great Chalfield is as pretty an English country house as you can imagine.

The 15th-century moated manor house is set in tranquil countryside and features a gatehouse and stunning oriel windows, all of which withstood a siege by Royalists during the English Civil War. The private residence offers guided tours, or you can book into one of Chalfield Manor’s reasonably priced gorgeous four-poster bedrooms for the night.

14. Burghley House, Lincolnshire

Burghley is one of England’s great Elizabethan houses. Credit: Andreas von Einsiedel/AlamyDescribed as ‘England’s greatest Elizabethan house’, Burghley was built and designed by William Cecil, Lord High Treasurer to Queen Elizabeth I, between 1555 and 1587. Its grounds includes 2,000 acres of Capability Brown gardens, (which were added later), and a deer park.

Its grounds includes 2,000 acres of Capability Brown gardens, (which were added later), and a deer park.

The interior is lavish and features sumptuous fabrics and carvings by Grinling Gibbons. In the Pagoda Room are portraits of Queen Elizabeth I, King Henry VIII, Oliver Cromwell and members of the Cecil family.

Some say that beneath its foundations lie the remains of the medieval settlement of Burghley, mentioned in the Domesday Book, which so far has evaded archaeologists.

15. Mount Stuart, Isle of Bute

Mount Stuart is a house of many firsts. Credit: MST and Keith HunterIt may come as a surprise that the first house in Britain to have an indoor heated swimming pool is hidden on the tiny Isle of Bute in the Firth of Clyde in Scotland, but then Mount Stuart is no ordinary place. It was also probably the first property in Scotland to have electric lighting, central heating and a passenger lift – a horse-drawn railway was needed to build the house.

The Gothic Revival building, which replaced an earlier Georgian property, is a feat of Victorian engineering. It was created for John Crichton-Stuart, 3rd Marquess of Bute – the richest man in Britain in the late 19th century.

It was created for John Crichton-Stuart, 3rd Marquess of Bute – the richest man in Britain in the late 19th century.

16. Woburn Abbey, Bedfordshire

A Stag at Woburn Abbey Safari Park. Credit: VisitEngland/Woburn Safari ParkWoburn has been in the Russell family since King Edward VI gifted it to John Russell in 1547. In 1550 John was made the first Earl of Bedford.

It’s been the family seat since the 1620s and it was turned into the English Palladian home in the 1800s. The estate first opened to the public in 1955 and its impressive art collection includes the largest private collection of Venetian views painted by Canaletto on public view and the Armada Portrait of Queen Elizabeth I.

17. Longleat House, Wiltshire

Longleat is set amid 900 acres of Capability Brown landscaped parkland. Credit: VisitBritain/Britain on ViewCompleted in 1580, Longleat is another of our great Elizabethan houses and one of Britain’s best stately homes. Set in 900 acres of Capability Brown parkland, it also has one of the largest book collections in Europe. Look out for the bloodstained waistcoat of King Charles in the Great Hall – he reportedly wore it at his execution.

Look out for the bloodstained waistcoat of King Charles in the Great Hall – he reportedly wore it at his execution.

Now home to the 7th Marquess of Bath and run by his son, Viscount Weymouth, Longleat has come a long way from the property bought by MP John Thynne in 1540 for £53.

18. Llancaiach Fawr Manor, South Wales

Llancaiach Fawr Manor House was once visited by King Charles I. Credit: Keith Beeson/AlamyBuilt circa 1550 for Dafydd ap Richard, this house is a great example of a semi-fortified manor house. It’s laid out much as it would have been in 1645 when King Charles I visited. Charles must have angered the owner, Colonel Edward Prichard, as he switched allegiances to the Roundheads.

19. Luton Hoo, Bedfordshire

Luton Hoo is now a lavish hotelA house has stood at Luton Hoo since at least 1601 when Sir Robert Napier, 1st Baronet, purchased the estate. The house we see today dates from the late 18th century. At the time it was the seat of the 3rd Earl of Bute, then prime minister to King George III. Like many of Britain’s best stately homes, it too has Capability Brown designed gardens.

Like many of Britain’s best stately homes, it too has Capability Brown designed gardens.

Guests at Luton Hoo hotel can enjoy the Edwardian Belle Epoque interiors introduced by the people behind the Ritz. One highlight is the Wernher Restaurant, named after the owner who ordered the works. Over the years the estate has fulfilled many roles, including testing tanks during the Second World War.

Today it’s a fantastic place to get a taste of the English country life. Take afternoon tea or have a go at archery, much as past guests of its distinguished owners would have done.

20. Hatfield House, Hertfordshire

Hatfield House is easily accessible from LondonWithin easy reach of London, this Jacobean-style property was built for Robert Cecil, 1st Earl of Salisbury, on the site of Hatfield Palace. Cecil had exchanged Hatfield with King James I for the nearby Cecil family home of Theobalds.

Like the king, Robert Cecil wasn’t keen on the rather old-fashioned Hatfield Palace, which had been owned by King Henry VIII, and so he rebuilt it as Hatfield House.

It was here that Henry VIII’s offspring, Mary, Elizabeth and Edward played as children. Elizabeth was even supposedly told of her ascension to the throne at Hatfield.

The Marble Hall takes its name from the chequered black and white flooring where guests would have danced at balls. Guests were overlooked by the Rainbow Portrait of Queen Elizabeth I – perhaps the most colourful portrait of the Tudor era. The inscription ‘Non sine sole iris’, meaning ‘no rainbow without the sun’, reminds viewers that only the queen’s wisdom can ensure peace and prosperity.

21. Norton Conyers, North Yorkshire

Did Norton Conyers provide inspiration for Jane Eyre’s woman in the attic?It is one of the most enduring images in English literature: the mad woman locked away in the attic. And it was at Norton Conyers that Charlotte Brontë is said to have taken inspiration for her novel, Jane Eyre.

Charlotte Brontë visited the medieval house in 1839, before she wrote her seminal novel. Could it be mere coincidence that Norton Conyers has its own legend of a woman hidden in an attic? The discovery of a blocked staircase in 2004, much like the one in the novel, seemed to confirm the theory. The house has recently been restored and reopened to the public on a few select days each year, and is most definitely one of Britain’s best stately homes.

Could it be mere coincidence that Norton Conyers has its own legend of a woman hidden in an attic? The discovery of a blocked staircase in 2004, much like the one in the novel, seemed to confirm the theory. The house has recently been restored and reopened to the public on a few select days each year, and is most definitely one of Britain’s best stately homes.

22. Blickling Hall, Norfolk

The South Drawing Room at Blickling Hall. Credit: National Trust Images/Nadia MackenzieWas this red brick mansion built on the site of the birthplace of Anne Boleyn? The house was built on the ruins of the former Boleyn home during the reign of King James I. Anne’s parents lived here from 1499 to 1505, so if Anne was indeed born in 1501 then it’s highly probable.

On the staircase of the Great Hall there are reliefs of Anne and her daughter, Queen Elizabeth I. Anne’s ghost is also said to appear carrying her severed head every year on the anniversary of her execution. The South Drawing Room, with its Jacobean-style chimneypiece and ceiling, is also highly impressive.

23. Montacute House, Somerset

Montacute House. Credit: National Trust Images/Stuart CoxThis late Elizabethan house was Greenwich Palace in TV’s Wolf Hall and is considered a masterpiece of Renaissance architecture. The house’s biggest draw by far is its Long Gallery, the longest of its kind in England. Montacute’s Long Gallery displays over 60 Tudor and Elizabethan portraits loaned to the house by the National Portrait Gallery.

24. Sudeley Castle, Gloucestershire

Sudeley Castle is the final resting place of Catherine Parr. Credit: VisitBritain/Britain on ViewThe final resting place of King Henry VIII’s last wife, Catherine Parr, this beautiful private castle is perhaps as well known for its colourful gardens as its restored Tudor buildings.

Situated in the heart of the Cotswolds, in an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty, just a few miles from Broadway, Sudeley lay in ruin for almost 200 years following the English Civil War when Cromwell ordered its ‘slighting’, until an ambitious restoration project began in 1837.

25. Somerleyton Hall, Suffolk

Somerleyton Hall is open to the public from April to SeptemberThis gorgeous Tudor palace opens to the public from April to September. It grounds feature one of Britain’s finest yew hedge mazes and a 70ft-long pergola, and it is deservedly on the list of Britain’s best stately homes.

Read more:

British book settings you can visit

Win a two-night stay in the Scottish Highlands

Your July/August 2022 issue is here!

The Best Stately Homes in England You Can Visit

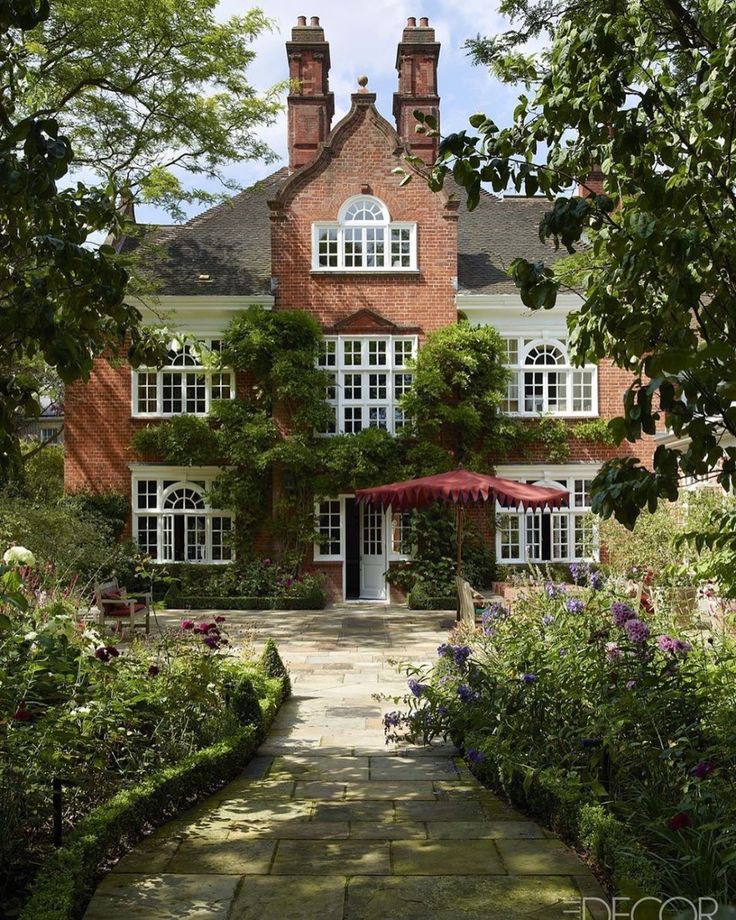

Jess and I both love visiting the stately homes in England. These imposing constructions were generally built to house the aristocratic families of the country, and tend to be rather grand affairs with formal rooms, impressive architecture and, depending on the whims of the owners, some form of landscaped garden.

These homes, which are generally in the country, can also be referred to as Country Houses or Country Homes, and they are where the gentry would retire to when not hanging out in the cities taking part in the social scene. Clearly, a tough life, but someone had to do it.

During the 20th century though, and for various reasons, many of Britain’s aristocratic families ended up short on funds and so weren’t able to keep these homes maintained. One of the ways around this was to open them up to the public (or sell them to a public body), which means that today a great many of England’s finest homes and palaces are open for touring.

Some of these are still privately owned, whilst others have been given to national organisations such as the National Trust and English Heritage for ongoing maintenance and upkeep.

In today’s post, I want to share with you ten of my favourite stately homes that you can visit in England. Note that this doesn’t include major Royal Palaces like Windsor or Hampton Court – that’s going to be a whole post of its own!

I’m also just sticking to England for this one. As you can imagine, there were hundreds to choose from across the country, but I feel that each of the ten options in this post is well deserving of its title as one of the:

As you can imagine, there were hundreds to choose from across the country, but I feel that each of the ten options in this post is well deserving of its title as one of the:

Best Stately Homes in England to Visit

1. Blenheim Palace

Blenheim is the only property in Britain which carries the title “Palace”, but is not Royal. Instead, it’s the principal residence of the Dukes of Marlborough (the family still lives on site), and is both a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and one of the largest houses in England.

It’s also notable as being the birthplace of Sir Winston Churchill, and is the ancestral home of the Churchill family.

The house and grounds today are open to the public, and are a truly grand place to visit. You could easily spend a full day here, picnicking by the lake, enjoying the English Baroque architecture, touring the Winston Churchill exhibit (he also proposed to his wife on the grounds) as well as taking in the gloriously opulent state rooms and wandering the park and gardens which in their current form were designed by renowned landscape gardener Capability Brown.

It’s a good day trip from London, and could also be combined with a visit to nearby Oxford. Read more about our experiences visiting Blenheim on a day trip from London here, and book your tickets in advance here to save the queue. You can also book a day trip from London which includes Blenheim here.

2. Chatsworth House

Nestled in the Derbyshire Dales, near England’s Peak district, Chatsworth House has topped lists of the UK’s favourite country house numerous times. And it’s not hard to see why – the impressive building, surrounded by 105 acres of garden and 1,000 acres of park land is truly wonderful to behold. No wonder that 300,000 people come here every year for the garden alone!

Of course, there’s more to Chatsworth House than the garden, although with the fountains, rockeries and cascade feature, you could be forgiven for spending a whole day just in the garden.

The house itself has been home to the Cavendish family, also known as the Dukes of Devonshire, since 1549, and has been added to and extended throughout the years. The family do still live here, and of the 126 rooms, only around 20 or so are open to the public. Still, they are large, impressive and richly decorated, so a tour is well worth the entry fee.

The family do still live here, and of the 126 rooms, only around 20 or so are open to the public. Still, they are large, impressive and richly decorated, so a tour is well worth the entry fee.

Another notable feature of Chatsworth are the excellent dining options, with three on-site restaurants as well as two cafe’s. One of these restaurants, the Flying Childers, specialises in afternoon tea, and naturally we had to try that out. Served on Wedgwood, the afternoon tea was a sumptuous affair, and one of the best we’ve had in the UK.

If you’re looking to take your country house visit to the next level, an afternoon tea is definitely a good way to do so! For ticketing and further information, see the official Chatsworth House website. Hint – if you book online, you get free parking. You can also visit as part of this 3 day tour from Manchester.

3. Highclere Castle

Fans of the TV series Downton Abbey will instantly recognise Highclere Castle because it stands in as the main house in the show. Whilst Downton Abbey itself is fictional, this is a striking building nonetheless, and well worth visiting, even if you’re not a fan of the show.

Whilst Downton Abbey itself is fictional, this is a striking building nonetheless, and well worth visiting, even if you’re not a fan of the show.

As it happens, Jess is a huge fan of the show, and so did the whole tour. I was quite impressed with the gardens and exterior of the property, so entertained myself wandering around and waiting for the clouds to clear and the people to move so I could get a nice photo.

In terms of the building and grounds, well, like all the properties so far, the gardens had Capability Brown’s involvement (he was a busy chap!), whilst the property itself dates from 1679. It’s the home of the Earl of Carnarvon (famous for the discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb – there’s an Egyptian Exhibition to celebrate this), and is open through the summer, as well as on select dates throughout the year.

Whilst general admission tickets on the official website often sell out, we have been reliably informed that if you turn up at the property you are very unlikely to be turned away. Another option is to take a day tour from London like this one which includes transport and admission.

Another option is to take a day tour from London like this one which includes transport and admission.

We have a full guide to visiting Highclere Castle to help you plan your trip.

Don’t miss the café on site for delicious scones, or the Secret Garden. Highclere Castle is about an hour’s drive south of Oxford, or a couple of hours from London – you could visit as a day trip from either, and also include Stonehenge, if you were so inclined. Check out my UK Itinerary post for more ideas on trips around the UK.

4. Wentworth Woodhouse

If my list of stately homes was a family tree, Wentworth Woodhouse would probably be the crazy uncle that no-one talks about. It’s a property of mindboggling proportions, unbelievable in so many ways, and yet most people have never heard of it.

It’s also a bit of an odd one to include, largely because at the time of writing this post, I don’t know for how long it is going to be open to the public for. My advice to you is, if you can get to it, and it is open, to visit as soon as you can. Whilst the property is currently owned by a Trust, with government money being allocated for restoration, there always appears to be the risk that it might return to private ownership and be closed to the public.

Whilst the property is currently owned by a Trust, with government money being allocated for restoration, there always appears to be the risk that it might return to private ownership and be closed to the public.

If that happens, it would definitely be a tragedy, because this property is, as I mentioned, just bonkers. Some quick facts to blow your mind:

Wentworth Woodhouse is the largest private home in Europe. It has over 300 rooms (no-one actually knows how many), 23,000 square meters of floor space and the property alone has a footprint of 2.5 acres. It’s so big that some guests left breadcrumb trails to get back to their rooms after dining as otherwise the chances of getting to bed were slim. Oh, it also has the longest country house façade of any house in Europe (606 feet long), and is so big that the front and the back look like two completely different properties.

So why has no-one really heard of this place?

Well, unfortunately, the house, and in particular the original gardens, have suffered their share of troubles over the years. The property sat on a huge coal seam, and just after the second world war, the UK government turned the grounds into the UK’s largest open cast mine site, causing huge devastation to the formal gardens, as well as potentially resulting in subsidence issues under the property itself.

The property sat on a huge coal seam, and just after the second world war, the UK government turned the grounds into the UK’s largest open cast mine site, causing huge devastation to the formal gardens, as well as potentially resulting in subsidence issues under the property itself.

Over its lifetime, large portions of the property have been unoccupied, and as such, a lot of restoration work is required. This might be a slight understatement. The rooms are empty for the most part, and a tour is certainly a different experience to many of the other properties on this list. Still, I absolutely urge you to visit if you can, the vast scale of the property is just incredible to behold, and the people who work here are deeply passionate about Wentworth.

If you’re interested in learning more about the history of the family and house, Jess recommends the book “Black Diamonds”, which charts the rise and fall of the Fitzwilliam family, previous owners of the house. Jess has also written a very comprehensive post all about visiting Wentworth Woodhouse, which you should definitely check out. Then, book your tour on the official website and get yourself along to this stunning property.

Then, book your tour on the official website and get yourself along to this stunning property.

5. Chartwell House

Another property makes the list with a link to Winston Churchill. In fact, we’ve recently visited so many Churchill sites that Jess has written a whole post dedicated to visiting Winston Churchill sites in England.

In this case, Chartwell House was Churchill’s home, from when he and his wife Clementine purchased it in 1922, through to Sir Winston’s death in 1965, at which time Clementine presented it to the National Trust, who still own and look after the property today.

This is certainly not as grand or ostentatious a property as many of the others on this list. Whilst a property has been on the estate since the 16th century, the Churchill’s made so many changes upon their purchase that it’s essentially completely transformed. This is actually a good thing, because the 19th century version of the property was not favourably thought of.

The property is very much worth visiting, because it gives an impression of the home life of the man who was at the centre of a number of world events through the 20th century, who also happened to find time to win a Nobel Prize for literature, paint award winning landscapes, raise butterflies and build walls. So yes, definitely worth the visit. Note that Chartwell runs timed tours and it gets busy here, so we recommend arriving early in order to be in with a good chance of seeing the property close to your preferred time!

Like a number of other properties on this list, Chartwell House is a National Trust property, so it’s free to National Trust members and visitors with a National Trust touring pass. See more at the end of the post for ways to save money on entry to the properties on this list.

6. Osborne House

Ok, I promised no Royal Palaces or Castles, so this one is a bit of a cheat. This isn’t technically a palace or a castle, but is definitely associated with Royalty – it was Queen Victoria’s holiday home, and it can definitely be described as palatial – at least in size!

It can be found on the Isle of Wight, just off the south coast of England, and feels much like an Italian villa. It was purpose built in the 19th century for Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, and so reflects their style and tastes.

It was purpose built in the 19th century for Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, and so reflects their style and tastes.

It also had to be large enough to accommodate their extensive family, and there are parts of the grounds which were dedicated to the children’s use and education, including a miniature fort and vegetable gardens.

As you can imagine, it’s well worth exploring the house and the grounds (currently 354 acres) – in particular don’t miss the beach, which was for the private use of the Royal Family.

The house is now owned by English Heritage and open to the public, check the official website for pricing and opening times. You book your tickets online in advance here.

Osborne House is operated by English Heritage, so there’s a fee to visit. It’s free for English Heritage members (sign up here, available to everyone), or holders of the English Heritage Overseas Visitors Pass (non-UK residents only, buy yours here).

See more at the end of the post for saving money on entry to the properties on this list.

If you are visiting the Isle of Wight, do also take a look at our guide to spending two days on the Isle of Wight, as well as Jess’s guide to Queen Victoria sights on the Isle of Wight.

7. Newstead Abbey

In the heart of Nottinghamshire, Newstead Abbey is most famous for being the home of noted British poet Lord Byron. Originally though, as the name suggests, this was a religious building, home to a number of Augustinian monks. However, when Henry VIII decided to disband all the Catholic houses, including monasteries, the Abbey was handed over to the Byron family.

Lord Byron the poet inherited the property when it was badly in need of repair, and initially he lived in nearby Nottingham, using the grandly crumbling ruin as handy poetic inspiration.

Later, he moved into the property and did attempt various restorative works, but these were generally of an artistic nature rather than anything usefully structural, and so the property continued to decline, until it was finally bought in 1818 by someone with sufficient funds to restore it to some of its original glory.

Finally, after passing to various people, it was gifted to the city of Nottingham, and today it is owned and maintained by Nottingham City Council, and can be toured both inside and outside.

It’s a fascinating property to look at, as part of it is an old abbey ruin, with the house built onto the side of it. There are wonderful gardens to explore, including an American Garden, a Japanese Garden and a walled garden.

The tour of the property naturally focuses on its most famous resident, but there are plenty of tales about the property and its other owners that will fascinate you. All in all, a very worthwhile half day visit.

8. Apsley House

I appreciate that pretty much every house in this list requires a bit of effort to get to – either you’re going to have to find your own transport, or you’re going to have to book a tour. With that in mind, and in particular for those of you just visiting London, I wanted to give you an option that’s right on your doorstep – Apsley House.

Ok, so it’s not exactly a grand stately home, or a country house at all, but it’s impressive nonetheless, and will give you an idea at least of the aristocratic lifestyle if you don’t have time to head out of London, or want to visit somewhere that isn’t a Royal Palace.

This is on Hyde Park Corner, so it’s right in the heart of London, just around the corner from Buckingham Palace. It’s the family home of the Dukes of Wellington, and is a spectacular example of an aristocratic town house.

The house is still occupied by the Dukes of Wellington, however most of it is now open to the public and serves as a museum, primarily to the first Duke of Wellington, who famously defeated Napoleon at the Battle of Waterloo, and is widely regarded as one of the greatest British military commanders in history.

Apsley House today houses a superb art collection, much of which was acquired as the spoils of war, as well as gifts from admirers around the world, which include paintings, sculptures, silver, porcelain and more. There’s an excellent audio guide which will take you around the house, which we definitely recommend.

There’s an excellent audio guide which will take you around the house, which we definitely recommend.

Apsley House is operated by English Heritage. In terms of entry fees, it’s free to English Heritage members, those holding an English Heritage Overseas Visitor Pass or you can pay a one-off ticket price.

It’s also included on the excellent London Pass – if you are planning on seeing a number of sights in London, then we can definitely recommend picking one of those up for your visit. Read Jess’s full review of the London Pass to see if it will save you money on your trip.

9. Baddesley Clinton

Baddesley Clinton is the only moated property on this list, which in my book, warrants its entry alone. Technically a manor house, Baddesley Clinton dates from the 13th century, and was the property of the Ferrer family for 12 generations before passing to the National Trust.

The house has seen its fair share of history, with particular note being the role it played during the Catholic persecutions of the 16th century. In particular, there are three “priest holes” in the property, where priests could hide to avoid capture.

In particular, there are three “priest holes” in the property, where priests could hide to avoid capture.

There are also lovely gardens to explore and the property has notably beautiful stained glass windows. It’s definitely a little different to some of the other properties on this list, hence the inclusion.

Again, as a National Trust property, Baddesley Clinton is free to National Trust members and visitors with a National Trust touring pass. See more at the end of the post for saving money on entry to the properties on this list.

10. Attingham Park

Last, but by no means least on my ten favourite stately homes to visit in England is Attingham Park. This 18th century mansion and estate is the fourth most visited National Trust property in the UK, and when you visit you’ll quickly understand why.

Built in 1785, the building is imposing and impressive, with a huge main façade and two single storey wings jutting out from either side. The interior is equally grand and well maintained, with a marked difference between the “upstairs” and “downstairs” lifestyles on show.

The interior is equally grand and well maintained, with a marked difference between the “upstairs” and “downstairs” lifestyles on show.

When we visited we took a behind the scenes tour of the new picture gallery roof. This might not seem that exciting, but given the original was designed by John Nash (architect of Buckingham Palace, along with a great number of buildings of Regency London) using radical design technologies for the time, this turned out to be quite fascinating.

We also learnt about the history of the owners and occupants of the property – stories that involved romance, loss, ruin and restoration. So basically something for everyone!

Again, there’s enough here to do for at least half a day of exploring, and there’s an excellent café on site in the stable block. This is also a National Trust property – you know the drill by now in terms of how the pricing works.

Map of Stately Homes in England

The houses I’ve chosen are all around England, so I don’t expect you to be able to visit them all in one trip. I have two posts with suggested UK itineraries, and some of these houses could easily be added to either of those. You can see the two week UK itinerary here, and the one week UK itinerary here.

I have two posts with suggested UK itineraries, and some of these houses could easily be added to either of those. You can see the two week UK itinerary here, and the one week UK itinerary here.

As a guide though, here’s a map showing all the locations of the Stately Homes in this post for quick reference.

Tours that Visit Stately Homes in England

As you can see from the map, the stately homes we have recommended are spread out across the country, meaning that if you don’t have your own transport, it can be challenging to reach them, even by public transport.

To help you get around this issue, we’ve found a number of tours that will get you to some of the properties on this list. Whilst not every home can be visited as part of a tour, the more popular and closer to London the property is, the greater the chance of their being a tour! Here are some tour options for you to consider:

- This private tour to Chartwell House from London, which includes round-trip transport from your hotel, entry fee to Chartwell, and a private guide and driver

- This full day tour of Highclere Castle from London, which includes your entry fee to Highclere Castle, as well as a number of other Downton Abbey filming locations

- This full day tour of Blenheim Palace, the Cotswolds, and some Downton Abbey filming locations, which also includes entry to Blenheim and an audioguide

- A 5 day tour of England and Wales from London, which includes Chatsworth House amongst many other locations!

As you can see, you have a few different options for visiting these stately homes, even if you don’t have your own transport.

Passes for Visiting Stately Homes in England

Many of the houses in this list are privately owned, and so have their own entry fees. Usually, it’s worth checking online at their official websites to see if they are running any offers – such as the free parking at Chatsworth if you book online.

A number of the other properties are part of national organisations such as the National Trust or English Heritage.

In those cases, if you are planning on visiting a number of properties operated by these organisations then you may be better off purchasing an annual membership instead of paying individual prices. You only need to visit a few properties in each case to make up the cost of membership.

You can buy an English Heritage Membership here and a National Trust membership here.

If you’re only visiting the UK for a shorter trip there are specific passes for visitors for both the National Trust and English Heritage, which represent great value for money for visitors.

For the National Trust you can pick up a National Trust touring pass. This is valid for 7 or 14 days, and gives you access to every National Trust property in the UK.

For English Heritage, you can get an English Heritage Overseas Visitor Pass. This is valid for 9 or 16 days, and gives you access to every English Heritage property in the UK.

In addition, some overseas organisations have reciprocal arrangements with the National Trust and English Heritage – meaning if you are a member of an overseas organisation you may have free entry already.

You can see on their websites both the reciprocal arrangements and a full list of covered attractions. See those on the National Trust website here, and English Heritage here.

Finally, as already mentioned in the post, if you’re visiting London, then you can save a good pile of money by investing in a London Pass for your stay, which gives you access to a good many London attractions.

Further Reading

We’ve written a number of posts and guides to travel in the UK that you might find useful for planning a trip. We also have a number of books and online resources that you might find helpful, both related to Stately Homes, and general travel in the UK. Here they are:

- We have guides to many of the cities and sights in the UK for you to bookmark, including:

- We have a full guide to visiting Highclere Castle to help you plan your trip.

- A Two Week UK itinerary & A One Week UK Itinerary

- A Two Day London Itinerary, as well as a Six Day London Itinerary

- The Best Photography Locations in London

- Tips on Buying and Using the London Pass

- Planning an Oxford day trip from London

- The Highlights of Oxford

- Visiting Blenheim Palace and the Cotswolds

- A Guide to Touring the Scottish Borders

- A Guide to visiting Stonehenge from London

- The Best Harry Potter Locations in London

- In terms of reading related to Stately Homes, you might enjoy:

- Black Diamonds – the tale of Wentworth Woodhouse

- England’s Thousand Best Houses – this should give you plenty of ideas for more places to visit!

- If you want a physical (or digital!) book to accompany your travels, then Amazon have a great selection.

We recommend the Rick Steves England book, & the Lonely Planet Guide to get you started.

We recommend the Rick Steves England book, & the Lonely Planet Guide to get you started.

And that finishes up my post on some of my favourite Stately Homes to visit in England! Got a favourite you’d like to share, or any questions about the post? Let us know in the comments below!

England's Finest Stately Homes / England

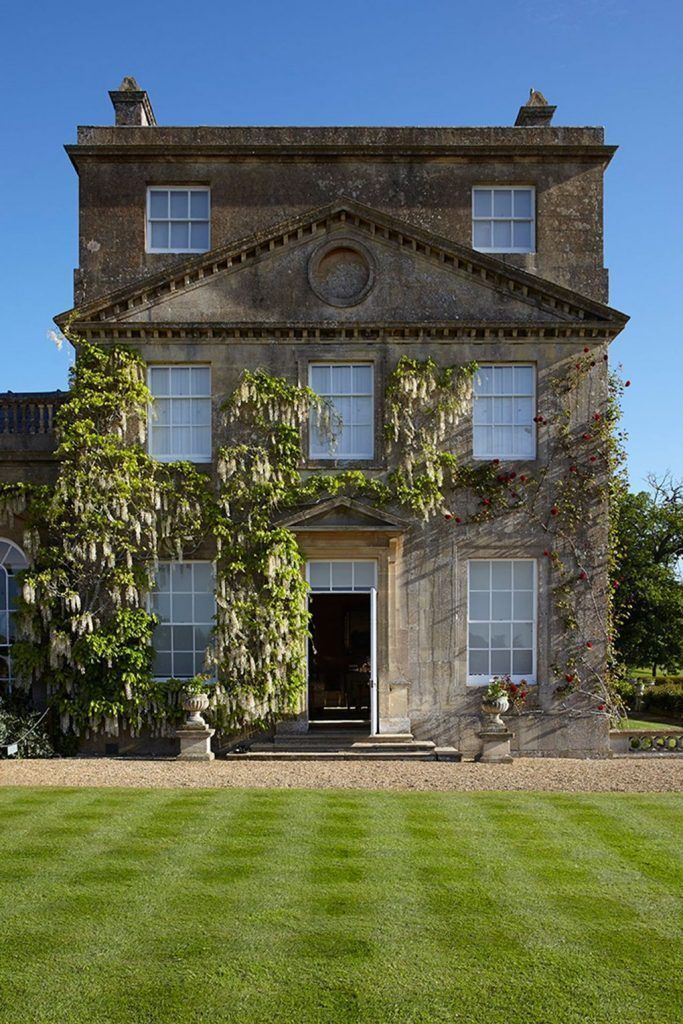

Green. Pleasant. We all have our own fantasies of the island of skype, and fortunately for us, they are still embodied in the stately homes of England - rich in layered history, set in the gardens of Arcadia, enticing us with their glimpses of past centuries. Here are five of our favorites.

Chatsworth

The most luxurious, longtime ducal throne and one-time prison for Elizabeth I.

Known as the "Palace of the Peak", the huge building of Chatsworth was occupied for centuries by the Dukes of Devonshire. The original house was founded in 1551 by the inimitable Bess of Hardwick; a little later came Chatsworth's most celebrated guest, Mary Queen of Scots. She was imprisoned here and back between 1570 and 1581 by order of Elizabeth I, guarded by Bess's fourth husband, the Earl of Shrewsbury. The Scots Bedrooms, nine regency rooms named after the imprisoned queen, are sometimes open to the public. The house is set in gardens of 25 sq. Miles, where the fountain is so high that it can be seen for many miles in the hills of the Dark Peak, and several bold modern sculptures, of which the Duke and Duchess of Devonshire are keen collectors..

She was imprisoned here and back between 1570 and 1581 by order of Elizabeth I, guarded by Bess's fourth husband, the Earl of Shrewsbury. The Scots Bedrooms, nine regency rooms named after the imprisoned queen, are sometimes open to the public. The house is set in gardens of 25 sq. Miles, where the fountain is so high that it can be seen for many miles in the hills of the Dark Peak, and several bold modern sculptures, of which the Duke and Duchess of Devonshire are keen collectors..

Chatsworth is 3 miles northeast of Bakewell. Buses 170 and 218 go directly from Bakewell to Chatsworth (15 minutes, several times a day). On Sunday, bus 215 also runs to Chatsworth.

Castle Howard

So strong striker, he should stand behind the fantasy mansion in Return to Brideshead.

Stately homes in England may be a couple of pennies, but you'll have to work hard to find a work of theatrical grandeur and audacity that is as stunningly majestic as Castle Howard, unfolding in the Howardian Hills. This is one of the most beautiful buildings in the world, immediately recognizable by its starring role in Return to Brideshead - which has made its popularity an endless favor since the series first aired in the early 1980s. It took three of the count's lives to build; it's still home to the Howard family these days, but you can take a tour of the house and grounds (eighteenth-century walled garden, roses, delphiniums, temples, fountains and all). Castle Howard is located 15 miles northeast of York, off the A64. There are several organized tours from York - check with the Tourist Office for schedules..

This is one of the most beautiful buildings in the world, immediately recognizable by its starring role in Return to Brideshead - which has made its popularity an endless favor since the series first aired in the early 1980s. It took three of the count's lives to build; it's still home to the Howard family these days, but you can take a tour of the house and grounds (eighteenth-century walled garden, roses, delphiniums, temples, fountains and all). Castle Howard is located 15 miles northeast of York, off the A64. There are several organized tours from York - check with the Tourist Office for schedules..

Hardwick Hall

At the time it was built, glass was a status symbol - and Hardwick Hall is "more glass than a wall".

This Elizabethan Hall should be high on your list of must-see stately homes. It was the home of the second most powerful woman of the 16th century, Elizabeth, Countess of Shrewsbury - known to everyone as Bess of Hardwick. Bess's fourth husband died in 1590, leaving her with a huge pile of money to play with, and she built Hardwick Hall using the designs of the eminent architect Robert Smithson. Glass was a status symbol, so she went all out on all the windows; as a contemporary put it, "Hardwick Hall is more glass than walls." Also magnificent are the Great Chamber and the Long Gallery.

Glass was a status symbol, so she went all out on all the windows; as a contemporary put it, "Hardwick Hall is more glass than walls." Also magnificent are the Great Chamber and the Long Gallery.

Next door is Bess's first home, Hardwicke Old Hall, now a romantic ruin. Also spectacular are the formal gardens, and the hall sits in the expanses of Hardwick Park with short and long walking trails that lead through fields and woodland. Ask at the box office for details. Hardwick Hall is 10 miles southeast of Chesterfield off the M1.

Haddon Hall

This medieval masterpiece has hardly changed since the time of Henry VIII.

Described as a medieval masterpiece, Haddon Hall was originally owned by William Peveril, son of William the Conqueror, and what you see today dates mainly from the 14th to 16th centuries. The place was abandoned until the 18th and 19thcentury, so it escaped the "modernization" experienced by many other country houses. Highlights include the chapel; The Long Gallery bathed in stunning natural light; and a huge banqueting hall, virtually unchanged since the time of Henry VIII. Movie Elizabeth was shot here and, unsurprisingly, Haddon Hall made the perfect backdrop. Outside there are beautiful gardens and courtyards.

Movie Elizabeth was shot here and, unsurprisingly, Haddon Hall made the perfect backdrop. Outside there are beautiful gardens and courtyards.

Calke Abbey

Owned by the eccentric baronets, this stately home has hardly been airbrushed. Oh, and the tunnel!

Like a vast, abandoned study of wonders, Kalke Abbey is not your usual luxurious, opulent marquetry home. Built around 1703, it was taken over by a dynasty of eccentric and reclusive baronets. Not much has changed since 1880 - this is a mesmerizing example of the country house's decline. The result is a ramshackle maze of secret corridors, underground tunnels, and rooms crammed with old furniture, horse-drawn animal heads, dusty books, stuffed birds, and endless piles of britsa brach from the last three centuries..

Some rooms are in excellent condition, while others are deliberately left untouched, complete with crumbling plaster and moldy wallpaper. (You exit the house through a long, dark tunnel - a little more exhilarating than you'd like given the state of the buildings. ) Walking through the gardens is a similar time-drop experience - nothing has changed in the pot sheds since around 1930, but It looks like the gardener left only yesterday.

) Walking through the gardens is a similar time-drop experience - nothing has changed in the pot sheds since around 1930, but It looks like the gardener left only yesterday.

England

Stately home - frwiki.wiki

Stately , better known as house is in the Middle Ages until the end of XI - th to the middle of XV - th century, a large building, located mainly in the underground and his family.

More broadly, condition house , mansion or large house désignèrent later residence of the master of fortified farms (sometimes isolated), like houses , in XII - th century, can still be found, especially in Germany, England, France or Spain.

The current existence of the old "house" may be due to its isolation, the destruction of the buildings and walls that originally surrounded it, and the successive changes made over time to provide comfort for the dwelling or to "recycle" it into farmland. building, escaping the gaze of the traveler.

building, escaping the gaze of the traveler.

Castle of Beaumont-le-Richard in Englesquile-la-Perse.

Summary

- 1 Definition

- 2 Plan and assignment of parts

- 2.1 Cellar or storage room

- 2.2 Kitchen

- 2.3 Great Hall

- 2.4 Bedroom

- 3 Architectural components

- 3.1 Chimney

- 3.2 Facilities

- 3.3 Windows

- 3.4 Doors

- 3.5 High step ladder, removable or spiral in tower

- 3.6 Decorative elements

- 3.7 Ceilings

- 3.8 Frames

- 3.9 Roof

- 3.10 Buttresses

- 4 Some stately homes in France

- 4.1 In Alsace

- 4.2 In Maine

- 4.3 In Normandy

- 4.4 In Picardy

- 5 Some Stately Homes in Europe

- 5.1 Germany

- 5.2 In England

- 6 Links

- 7 External links

Definition

Hall of the Treasury at Cana ( XII - th century)

Owner of house is a knight, baron, earl, duke or king . .. in this particular case we are talking about the "royal house", the second house , used as a pied-à-terre during trips related to the control of the kingdom (inspection), or on vacation (vacation, hunting) - used as:

.. in this particular case we are talking about the "royal house", the second house , used as a pied-à-terre during trips related to the control of the kingdom (inspection), or on vacation (vacation, hunting) - used as:

- place of residence (himself, his family and comrades in arms) in peacetime. In the event of a threat or conflict, they took refuge in a high court or in a dungeon, if there was one. The smallest stately houses had as fortifications only buttresses, doorposts of double thickness, surrounding walls, and ditches that could be supplied with water. For this reason, the house was often erected by a stream (or spring for simple everyday matters).

- a conference room designed to receive his vassals and other honored guests, all decisions are made in the Great Hall or " village " in Latin (declaration of war, preparation for battle, economic management of possessions, etc.). In the Great Hall of Caen ("The Treasury"), Richard the Lionheart, King of England and Duke of Normandy, gathered his barons there before going on a crusade.

- court if conflicts have arisen on its land concerning ordinary people or people of high rank. These conflicts could only be resolved through an intermediary, namely the "lord", who alone had the decision of the court.

- Reception, where all ceremonies (dubbing, weddings, religious celebrations, etc.) took place. Robert de Torigny, abbot of Mont Saint-Michel reports that in 1182 over a thousand knights were present at the celebration of the Nativity in the Treasury Hall, the Great Hall of the Castle of Caen.

- place of worship, any "grand house" of any value with an annex converted into a chapel .

- treasury room where various taxes were collected.

[ref. need]

Plan and purpose of parts

Former residential area of Château de Creully (Calvados), 37 meters long.

Manor house has two levels in general:

- on the first floor there was a large pantry and a kitchen with a monumental fireplace; sometimes the kitchen could be on the first floor.

- 1 - th floor was divided into two parts, the larger hall or sometimes in a small house or hall a large hall, and also found in medieval texts (large hall for public use - reception room), where large meals or official organized ceremonies: weddings, dubbing, etc. It was also a place needed for judgments. The smallest room was the Lord's bedroom. This second floor could be reached by an external staircase called the grand stage.

In the largest stately homes we could find the Great Hall ( aula in Latin, great hall in English), in another type of building associated with the house.

[ref. needed]

Basement or pantry

Basement and pantry located on the ground floor of the house or semi-underground floor has the advantage of preventing the natural moisture of the soil from penetrating the upper floor of the dwelling and providing a place with a uniform temperature. , Fresh, allows you to save stocks of foodstuffs that could start fermenting if they were left exposed to changes in outside temperature, hence a minimum of windows. You can also find a vaulted kitchen (Brickebeck basement) or beams.

, Fresh, allows you to save stocks of foodstuffs that could start fermenting if they were left exposed to changes in outside temperature, hence a minimum of windows. You can also find a vaulted kitchen (Brickebeck basement) or beams.

Done

Sanctuary of Notre-Dame-de-Fontaine, La Briga (Alpes Maritimes), nave, south side wall, lower register of the Passion of Christ cycle: denial of St. Peter, kitchen example.

A rack with rings is hung in the chimney hood, allowing you to hang the cauldron more or less close to the fire, depending on the desired cooking method. Andirons supports magazines.

In this illustration of the Sanctuary of Notre-Dame-de-Fontaine, the object hanging on the hanger is a "kalen", a metal oil lamp, the hook of which, turned into a hook, can be grasped in various places.

In the kitchen of a stately home, very delicious meals could be prepared, which was the privilege of the dominant caste - the lower classes, of course, had no access to these delicacies.

[ref. need]

Great Room

In Old French we use the term grant sale or even just sale to denote this, an expression used in modern times in Great Hall ; in Latin texts the term is translated as aula . This grand hall, also called banquet hall or reception hall, is usually located on the second floor and is reached by a high staircase. It was usually equipped with a large fireplace designed for a kitchen with cooking utensils and was also used for heating. Dishes were stored in closets near the fireplace. You could also find a sink because hygiene was very strict in the Middle Ages; otherwise, we used an aquamanil, a double (container) or even a jug.

The room also had trestles for setting the table (hence the expression "setting the table" ) and benches. It was often decorated with wall paintings and tapestries.

Originally it was often a separate building, as in Oakham (County of Rutland, England), Caen, Dover-la-Delivrande (originally the Domaine de la Baronnie had a large room independent of the house), Brickbeck or Beaumont-le-Richard

Subsequently, the Grande Salle becomes a building associated with the house, as in Crépy-en-Valois (where the Grande-Salle and the house are in the same building), Creully ("see the evolution of the building"), Lillebonne or Penshurst. Location ( Baron's Hall)

Location ( Baron's Hall)

The royal or princely houses also had their Great Hall, much more imposing and luxurious than those of the little lords. Some of them are still famous for their size and beauty. This is the case of the Grand Salle at the Palais de la Cité in Paris, which was in its day, with its 1,800 square meters, the largest hall in Europe. It disappeared in 1618 in a fire, but the lower room, now known as the Salle des Gens-d'Armes, can still be seen in the Palais de Justice in Paris.

Examples of grand princely halls in France:

- Chinon, Great Hall of the castle, partially destroyed, where Joan of Arc was received by Charles VII.

- Loches, Great Hall of the Royal Lodge

- Poitiers, Great Hall, known as Hall Pa-Perdus in the Palais de Justice

Examples of large princely halls in Europe:

- England, London, Great Hall of the Palace of Westminster, Westminster Hall

- Czech Republic, the Great Hall of the Prague Castle, is called the Vladislav Hall.

Room, picture of the Temple Manor at Strode (Kent, n.

bedroom

The bedroom was adjacent to the Great Hall, separated by a simple partition. This room can be accessed through a hall or tower with a spiral staircase "access for private use". this room had a fireplace for heating and obviously a bed with medieval furniture... You can find a sink and a dustpan to wash it.

Architectural components

Fireplace

It is not likely that there were fireplaces in the interiors of palaces or Roman houses. Chimneys and fireplaces appear located in the interior, which XII - th century, and from this time examples abound. The primitive fireplace consists of a niche, taken at the expense of the thickness of the wall, stopped on each side by two legs, and topped with a mantle and a cap, under which smoke rushes. The fireplace served as both a heater and a place for cooking, depending on the room in which it was installed.

In the primitive house XI - century, there would be a central wood-burning fireplace (instead of a fireplace wall).

Chimney pipes and beams

- Chimney pipe XIII and centuries, usually cylindrical inside and completed over the stars or valleys in the form of a large column topped with a miter. Constructed with the utmost care with hollow stone foundations, these chimneys are often monumental in shape, gracefully climbing the tops of buildings.

Facilities

wall cabinet

Wall cabinet example.

A wall cabinet is a small room in a wall, enclosed, designed to store some valuable items or to store food. Sometimes they are ventilated, separated by stone or wooden planks. Such a closet was either by the fireplace, or in the kitchen, or in the bedroom.

Bathroom sink

- Usually it is placed in a niche, and an exhaust duct runs through the wall, ending with a gargoyle. Samples of civilian shells are very rare. In France, the oldest shell is found at Châtillon-Coligny, in a large fortress tower dating from around 1180.

These sinks had a scoop that was used to draw water into the sink.

Toilets

- The best-equipped and most comfortable dwellings had toilets whose masonry protruded from the side of the outer wall (“ledge latrines”, then “slanted duct toilets”, toilets located in the thickness of the wall, and the duct of which went directly to the facade at home). walls that caused olfactory and visual pollution) or in the very thickness of the wall (“cesspools”), at the foot of which excrement was evacuated, which nature reintegrated into its cycle, as they fell between trees or into the water a protective ditch built around the building .

Window

There are different types of windows, all of them bevelled (a beveled surface obtained by lowering the edge of a stone):

# geminate: arranged, grouped in twos, in pairs from Latin geminare to double

- single or double watchtower small chamfered window designed as a watchtower as the name suggests

- post: a fixed vertical section that divides a window into compartments, especially in medieval and renaissance architecture (may be crossed by one or more brackets)

- Claire Voy: set of adjoining windows "relatively rare in Anglo-Norman houses"

[ref. needed]

needed]

Doors

The doors were bevelled.

Arched front door.

Doors of external and internal civil buildings.

In medieval towns, only castles and palaces had wagon gates, which were usually fortified. As for the doors of the houses themselves, these dwellings, if they were equipped with courtyards, would always have only what we call passage doors, that is, adapted only for pedestrians, with a width of 1 m up to 1.50 meters and height. 2.50 to 3 meters maximum.

Unknown, doors of civil buildings dating back to XI - th century in France, which have a special character. The entrance bays, very rarely, moreover, in this period, consist of only two jambs with a semicircular arch in a small arrangement, and do not differ from the small church doors that we still see open on the sides of some religious monuments of Beauvaisis, Berry, Touraine and Poitou.

High step staircase, removable or spiral in the tower

- For installation on the top floor of the house, it was installed, from XII - th century, long straight slopes with a parapet at the top. The steps were based on arches and always outlined on the outside, which allowed the step to be given a large width and had a very good effect, indicating the purpose of these very long ramps.

- Revolving ladder

Houses, mansions and dungeons could be equipped with this type of stairs, the inhabitants of which wanted to provide more security from possible intrusions. Installed in a circular tower in a stone cylinder pierced by doors at the height of the serviced floors, the staircase did not depend on the masonry and consisted of a pivot axis supporting the entire frame system. For each serviced floor, a masonry platform was equipped.

We must assume that all doors are drilled above the D on the first floor. The first step is in E; from E to F, the steps are fixed and independent of the core of the frame, mounted on the lower iron rod G and held at the top by a screw along a circle taken by two horizontal pieces of wood. The first stage assembled in the core is H; she and the next three are heavily freed from the gallows.

The first step is in E; from E to F, the steps are fixed and independent of the core of the frame, mounted on the lower iron rod G and held at the top by a screw along a circle taken by two horizontal pieces of wood. The first stage assembled in the core is H; she and the next three are heavily freed from the gallows.

From this light step H begins a spiral stringer, assembled at the ends of the steps and carrying a cylindrical wooden partition pierced by doors to the right of the stone compartments D. Above the third step (starting from this H) other steps rise up. to the top of the screws are loosened only by small links K, shorter than the brackets I, to facilitate detachment. Thus, all steps, the stringer and the cylindrical partition rest on the rotary shaft O. When we wanted to close all the doors of the floors at once, it was enough to make the cylinder make a quarter circle by turning on the rod. its axis. Therefore, these doors were hidden; There was a gap between step F and step H, and people who would have crossed it to enter the apartments, finding the wall opposite the holes made in the cylinder, could not guess the location of the real doors corresponding to these holes when the Staircase was returned to its place. A simple stop placed by the occupants on one of the C bearings prevented that screw from turning. It was a sure way to avoid intruders. See Removable ladder .

A simple stop placed by the occupants on one of the C bearings prevented that screw from turning. It was a sure way to avoid intruders. See Removable ladder .

- Spiral staircases

They put two superimposed rooms in communication, they were not always taken due to the thickness of the walls; they were partially visible, located in the corner or along the walls of the lower chamber, tracery across this room. In this regard, it is important to familiarize yourself with the principles that guided the architects of the Middle Ages when building stairs. These architects never saw stairs as anything other than an appendage, necessary for any multi-story building, to be placed in the most convenient way for maintenance, as if the stairs were placed along the building. Under construction where the need arises. See spiral staircase .

decorative elements

- Frescoes

Observation of facts well known to archaeologists today leads us to consider here only the painting used in the French architecture of the Middle Ages. As in antiquity, painting and architecture were not separated. These two arts lent each other mutual assistance, and the "painting" as such (the decorative object of the wall) does not exist, or at least was only of very minor importance, and is also confirmed by the murals 14 century. Century.

As in antiquity, painting and architecture were not separated. These two arts lent each other mutual assistance, and the "painting" as such (the decorative object of the wall) does not exist, or at least was only of very minor importance, and is also confirmed by the murals 14 century. Century.

The first example of the device is very simple and the present image is a fresco in XII - th and XIII - th century above, white background yellow ocher, or, more often, brown red on a white or light yellow background ; lines thus drawn with a brush on large surfaces, simple, double, triple or accompanied by certain ornaments, are a very economical decoration, perfectly emphasizing liters, stripes, column bundles, borders, covered with more complex and brilliant ornamentation of color.

- floor coverings

- Installation of stone or terracotta tiles.

- Floor tiles

- Decorated tiles

- There is not known before terracotta XII - th century; one should not be surprised at how short the enamels with which this material is covered are; quickly wore out, terracotta tiles had to be changed frequently.

- Paving stone - Roman Opus

- Limestone, granite, slate, etc. depending on the geographical area and geological resources.

- At all times and in all countries, flat, hard, polished, adjacent stones, random or symmetrical, have been used to cover ground floor areas in private dwellings. Most limestone quarries have thin upper layers of dense texture, characteristic of this type of paving.

- Most of the dwellings were paved with large slabs of hard stone. Often, even in castles, these paving stones were decorated with inlays of colored stones or mastic, or the slabs alternated with painted stucco.

The story of the construction of the Bellver Castle (Spain) on the island of Mallorca is about the paving of this majestic home from stucco, consisting of quicklime, gypsum and large stones mixed with color; everything was so well polished that one would have thought that these areas were made of marble and porphyry .

The story of the construction of the Bellver Castle (Spain) on the island of Mallorca is about the paving of this majestic home from stucco, consisting of quicklime, gypsum and large stones mixed with color; everything was so well polished that one would have thought that these areas were made of marble and porphyry .

Ceilings

The ceiling in medieval buildings was only the floor, visible from below. The structure of the floor determined the shape and appearance of the ceiling, which was never covered with arches, bays and boxes of wood or plaster, decorative elements that had nothing to do with the basic function of simply dividing the space into two levels.

Beam examples.

Beams, often with a small span in the walls and more or less protruding from crow stone, could be decorated (at the edges) with profiles that went beyond the crow appearance. Sometimes the beams themselves were also molded very carefully. The beams of the oldest floors rested at one end only on these beams, and at the other - in a groove made in the wall, in holes or on a beam, which itself was placed on ledges or a continuous profile. To compensate for the twisting of these beams (not held in place by either spikes or pins), braces that form the dowels were attached at an angle between their spans, on beams and girders.

The beams of the oldest floors rested at one end only on these beams, and at the other - in a groove made in the wall, in holes or on a beam, which itself was placed on ledges or a continuous profile. To compensate for the twisting of these beams (not held in place by either spikes or pins), braces that form the dowels were attached at an angle between their spans, on beams and girders.

In interjoists the beam (full or empty) was applied to shingles or trimmed staves placed transversely. The butt joints between these planks are formed between the beams of the small boxes. These poles were covered with plaster or mortar, all covered with tiles.

Ceilings of rarely seen wood were tempera painted and could be easily refurbished. We still see many of these ceilings XIII - th and XIV - th century under the crate of the most modern in old houses.

Personnel

The frame of buildings, for example, in the Anglo-Norman regions, is similar to the naval frame. The Normans, seafaring people, apparently contributed greatly to the art of carpentry, as evidenced by, from XI - th century, large buildings are completely covered with large beams. High shots later in England, during XIII - th and XIV - th century seem to be more original, and built the oldest tradition.

The Normans, seafaring people, apparently contributed greatly to the art of carpentry, as evidenced by, from XI - th century, large buildings are completely covered with large beams. High shots later in England, during XIII - th and XIV - th century seem to be more original, and built the oldest tradition.

These frames can be very ornate and sculpted, usually made of oak or elm.

Frame example.

Roofing

- Crawl

The ramp is the sloping part of the roof gable.

- Ridge and ridge

These are the elements covering the top of the roof. These elements could be processed.

- Ridge

- Blanket

The roof can be tiled, lauze, slate, straw, etc. ; on geological resources.

; on geological resources.

Foothills

Masonry mass raised against a wall or support to support it. The buttresses have more of a reinforcement function than an aesthetic one.

Some stately houses in France

In Alsace

- Kientzheim Castle

- Castle Saint-Ulrich in Ribeauville

Maine

- Chateau de la Cour in Veseau

- Convoy at Saint-Cosme-en-Vayre

- Mirebo in Vivoin

In Normandy

- Brikvebek (1190)

- Ardevon (1220)

- Domaine de la Baronnie in Bretteville-sur-Odon

- Domfront (1100)

- Castle of Beaumont-le-Richard in Englesquile-la-Perse (1150)

- Damigny in Saint-Martin-de-Entre (1250)

- Crelly (1160)

- Treasury in Cana (1125)

- Le Mesnil-sous-Jumièges (c. 1200)

- Villiers-sur-Port to Port-en-Bessin-Huppin

- Ambley ( XIII - th - XIV - th th century)

- Crevecoeur-en-Auge

- Barony area in Dover-la-Délivrande ( XIII - th - XV - th th century)

- Château de Fontaine-Henri (1220), house much changed during the Renaissance.

- Rumesnil (1260)

- Manoir des Vallées in Barneville-la-Bertrand (1220)

- Loysale (1180)

- Glos-sur-Riesle (1220)

- Hongemar-Genouville (1240)

- Watteville-la-Rue (1100)

- Martin-Eglise (1220)

In Picardy

- Château Saint-Aubin in Crépy-en-Valois, today an archery museum.

- Manoir de Saint-Paterne (or Saint-Symphorien) in Pontpointe, Oise

Some Stately Homes in Europe

Germany

- Wartburg Castle

England

- Boothby Pagnell in Lincolnshire (c. 1180)

- Christchurch Constable House in Dorset (c. 1160)

- Burton Agnes old hall

- Strood

- Hereford (c. 1190)

Recommendations

- ↑ Palas in German, chamber block in English or chamber (room) in Latin texts)

- ↑ [[s: Dictionary of French Architecture from XI - to XVI - - Volume 6, Manor | Manor house in the medieval encyclopedia]]

- ↑ An example of a basement in Briquebeck

- ↑ house or big house on the Oise reference site

- ↑ Sanctuary of Notre-Dame-de-Fontaine, on the website of the Ministry of Culture

- ↑ see 9 different0065 twins (container)

- ↑ photo of Oklam Stately Home

- ↑ (in) view of Oakham Castle

- ↑ Okem Castle photo

- ↑ Kahn on the Normandy Worlds website

- ↑ Crelly Castle

- ↑ Lillebonne at Normandy worlds

- ↑ Baron's Hall

- ↑ [[s: Dictionary of French Architecture from XI - th to XVI - th century - Volume 2, number | room of the medieval encyclopedia]]

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j and k from Encyclopedia Viollet-le-Duc, Volume I Architecture

- ↑ [[s: Dictionary of French Architecture from XI - to XVI - - Volume 5, Window | Window to the medieval encyclopedia]]

- ↑ example of typical paintings of a stately home at Vinzel (Puy-de-Dome) (Auvergne)

- ↑ [[s: Dictionary of French Architecture from XI - to XVI - - Volume 4, Crete | Coat of arms in the medieval encyclopedia]]

- ↑ [[s: Dictionary of French Architecture from XI - to XVI - - Volume 5, Ridge | Ridge in the medieval encyclopedia]]

- ↑ [[s: Dictionary of French Architecture XI - th to XVI - th century - Volume 5, cob | Epi in the medieval encyclopedia]]

- ↑ [[s: Dictionary of French Architecture from XI - to XVI - - Volume 9, tiles | Tile in the medieval encyclopedia]]

- ↑ [[s: Dictionary of French Architecture from XI - to XVI - - Volume 1, slate | Slate in the medieval encyclopedia]]

- ↑ [[s: Dictionary of French architecture from XI - to XVI - - Volume 4, box | Counter-safe in the medieval encyclopedia]]

- ↑ Bricquebec on the website of the Ministry of Culture

- ↑ Seigneurial residence of Beaumont-le-Richard on the site of the worlds of Normandy

- ↑ Villiers-sur-Port on the website of the Ministry of Culture

- ↑ Manoir des Vallées on the website of the Ministry of Culture

- ↑ Loysale on the Normandy Worlds website

- ↑ Watteville-la-Rue on the site worlds of Normandy

- ↑ Boothby Pagnell's mansion at Norman Worlds

- ↑ Constable House in Christchurch

- ↑ Burton Agnes Old Hall at Norman Worlds

- ↑ English site Agnes Burton

- ↑ Category temples and mansions on Commons.

Learn more