Glass house conservatory

Classic Greenhouses & Conservatories

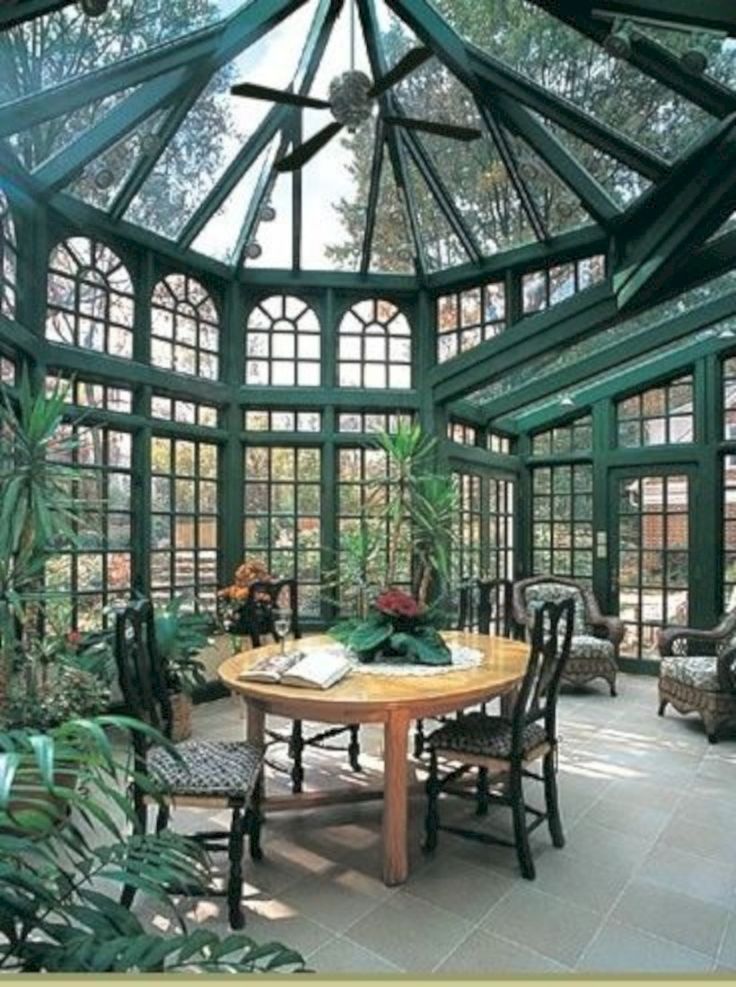

Tanglewood Conservatories of Denton, Maryland, custom-built this ornate glasshouse onto a renovated carriage house.

People who live in glass houses, as we all know, shouldn’t throw stones. People who want glasshouses, on the other hand, are just a stone’s throw away from a mind-crushing array of decisions.

The basic design of greenhouses and conservatories has changed so little over the last century that it’s no problem to find a style that’s old-house appropriate. You can buy a kit greenhouse similar to ones William Randolph Hearst ordered in the 1930s if you want to feel like Citizen Kane. If you really are flush, you can have an architect design a custom conservatory with over-the-top Victorian detailing. You can build green and have a new greenhouse created from historic parts. If you’re truly lucky, you may already have an old greenhouse or conservatory that can be restored with relatively little skill.

Some Semantics

The words greenhouse, conservatory, solarium, and sunroom have all been used interchangeably, depending on time and place. As a rule though, greenhouses are architecturally simpler but technically more complex buildings, intended for the winter survival or propagation of plants—perhaps to nurture strawberries for consumption in January. Conservatories can be sprawling structures built for ostentatious show of rare tropicals, or glass-walled rooms attached to houses, intended primarily for the pleasure of people.

Orangery was an early term for a conservatory, since this subtropical fruit was all the rage when first discovered by residents of temperate climes. There’s evidence that Pompeians were growing oranges behind mica windows in the 15th century before their run-in with Mount Vesuvius. Probably the world’s best-known orangery is the one Louis XIV built at Versailles in the last half of the 17th century.

Three greenhouses at the Lyman Estate in Waltham, Massachusetts, include this 1804 Grape House, containing vines started from cuttings taken in England in the 1870s. (Photo: David Bohl/Historic New England)

Some early greenhouses and conservatories looked like ordinary rooms with a disproportionate number of windows-masonry structures with a solid roof and a stone or packed-earth floor to stand up to moisture and plant clippings. In the 1700s a common design was a lean-to of south-facing glass with a brick wall to the north.

In the 1700s a common design was a lean-to of south-facing glass with a brick wall to the north.

Around the turn of the 19th century, the availability of cast iron made possible stronger structures with more sash. In 1816, English horticulturist J.C. Loudon invented a wrought-iron sash bar, less brittle than cast iron and cheaper than wood, which could be curved for glass domes. Loudon championed ridge-and-furrow glazing-what amounts to corrugated glass. With the ridge running north-south and panes facing east and west, greenhouses would get more gentle sun than with a flat southern exposure.

Because England taxed glass by weight until 1845, individual panes were still small and thin. Joseph Paxton, gardener to the Duke of Devonshire, seems to have bided his time until the glass-tax repeal before designing and building his famous Hyde Park Crystal Palace in 1851. Erected in 22 weeks, it covered 19 acres.

A restoration team at Hearst Castle is completing work on the second of two neglected greenhouses. One lacked a foundation; they built one, then buried it so the structure would look original.

One lacked a foundation; they built one, then buried it so the structure would look original.

The industrial prowess of the Victorian era easily accommodated stylistic excesses; conservatories got Gothic, Moorish, and even Anglo-Japanese touches. The structures often represented what one authority called a battle between architecture and horticulture. The Crystal Palace itself was unheated, and as the amount of glass in these buildings grew, better temperature control became imperative.

More humble early gardeners sheltered their crops in sash pits heated with decomposing manure or vegetable matter. The Dutch were among the first to heat larger greenhouses, using charcoal braziers. A common technology in the 1700s, both in the mother country and America, was hollow walls or flues that ran under the floor, allowing hot air or smoke to run the length of the building from a brick fireplace on one end to a chimney on the other.

By the late 18th century, the British were providing plants with both heat and humidity by steaming them with perforated pipes laid under stone or rock. Steam gave way in the mid-1800s to hot water heat. Especially efficient were the cast-iron boilers patented by Lord & Burnham in the 1870s, which could go without tending through an entire wintry night. These advances-by such other names as Hitchings, Pierson Sefton, American, Metropolitan, National, Foley, Lutton, Josephus Plenty, Ikes Braun (IBG), and Rough Brothers-created a boom in both private (at least for the wealthy) and commercial greenhouses.

Steam gave way in the mid-1800s to hot water heat. Especially efficient were the cast-iron boilers patented by Lord & Burnham in the 1870s, which could go without tending through an entire wintry night. These advances-by such other names as Hitchings, Pierson Sefton, American, Metropolitan, National, Foley, Lutton, Josephus Plenty, Ikes Braun (IBG), and Rough Brothers-created a boom in both private (at least for the wealthy) and commercial greenhouses.

The heyday of greenhouse construction ebbed with World War I, when many of the factories (including Lord & Burnham) were given over to munitions. As fortunes waned during the Depression, many of these grand structures were torn down or left to the forces of nature, and only Rough Brothers and National (now marketed by Nexus Corporation) are still in business.

From Dream to Reality

If you’re thinking of buying or building a greenhouse or conservatory, it’s imperative to know what you want. Do you see yourself entertaining guests in a glassed-in room with parquet floors where a few ficus trees manage to remain presentable? Or do you want to propagate rare orchids and staghorn ferns?

Mark Ward builds greenhouses, like this one on Brian and Kathy Hollen’s circa-1910 Virginia home, from recycled parts. Ward believes that old parts such as this vent wheel have more charm and integrity than new ones.

Ward believes that old parts such as this vent wheel have more charm and integrity than new ones.

Jim Smith and Mark Ward, who make their living restoring and rebuilding old glasshouses, say a lot can go wrong on both ends of the economic scale. “There’s an inherent conflict of interest,” says Smith, “between plants and oriental carpets.”

Smith was formerly head of restoration at Rough Brothers in Cincinnati and now operates his own company, Montgomery Smith. He’s been involved in such huge projects as the U.S. Botanic Garden and the Biltmore Estate and New York Botanical Garden conservatories. He also consulted on the restoration of the 1810/1903 greenhouse at Oatlands Plantation (a historic property outside Leesburg, Virginia), a relatively modest 33′ by 57′.

Avid gardeners wanting a small but historically detailed greenhouse can be disappointed by kits that yield what Smith describes as little hybrid Victorian pavilions with double ogee roofs that provide neither adequate venting nor shading.

Yet he’s also rescued a New England gardener who spent a small fortune on top-of-the-line growing benches and temperature control, only to invest in window sash more appropriate for a solarium. With no ventilation, heat and humidity were deteriorating the structure within six months.

Another client of Ward’s who, like the Hollens, has a heated pool in her greenhouse says it helps warm it—not to mention provides humidity for plants.

Shortly after earning his degree in social psychology 28 years ago, Mark Ward took on an intern project for a community garden. When the project fizzled, he found himself proud owner of the remains of a 3,000-foot commercial greenhouse. On his own, he learned that old glasshouses are considerably easier than Humpty Dumpty to put together again. For a while, he limited himself to reconstructing four or five greenhouses a year within a couple hours of his Concord, Massachusetts, base. But as he continued to amass vintage greenhouse remains, he concluded that what now amounts to some 100 tons of old cypress roof bars, cast-iron vent wheels, and galvanized supports will move faster if he travels farther and teaches his skills to local contractors.

People with moderate talent can repair old greenhouses, Ward says. Most structures are modular, similar to Erector sets, and so can be reborn smaller. New Jersey client Susan Shaw, for instance, paid $1,500 for pieces of a greenhouse originally 24′ by 56′ and Ward rebuilt it as a more manageable 12′ by 40′.

Greenhouses are more straightforward than old houses, where problems are often hidden behind plaster and molding. “It takes a certain logic,” Ward says, “but it’s mostly assembly work, cleaning and scraping, getting steel sandblasted and galvanized. Vents may be decayed and need to be taken apart and re-glued. The job is probably closer to finish carpentry than anything else.”

Factors to Consider

If you want a solarium—an attached sunroom where you will relax and grow a handful of plants—decisions are relatively clear-cut, since the materials involved will be familiar to most builders. Depending on how much glass they have they can overheat, so you may want skylights you can open. Remember that when it’s cloudy you need to crank up the heat, says Jim Smith.

Remember that when it’s cloudy you need to crank up the heat, says Jim Smith.

A greenhouse for growing a lot of plants brings up other issues, whether you’re buying or rebuilding:

Glazing with a lime-and-water mix prevents the restored Hearst greenhouse from overheating in summer.

Heat: Hot water systems in old greenhouses produce efficient, even heat, but can’t always be repaired easily. Smith says passive radiant heat is a close second choice. Ward’s client Susan Shaw says her attached greenhouse is warmed sufficiently by a heated pool and her home’s heating system. Another client, Brian Hollen, finds that his south-facing greenhouse helps heat his home, despite its location on a windy hilltop.

Ventilation: Greenhouses need a way for heat and humidity to escape. Vents can be as low-tech as simply opening windows, or be set to open and shut automatically via a computerized system that responds to temperature, wind, and rain.

Glass: For safety, greenhouse restorers usually replace old greenhouse glass with tempered glass, especially overhead. Ward says that, depending on the manufacturer, tempered glass can be wavy like old glass, with kind of a funhouse effect. Experts don’t always agree on whether the glass should be single- or double-glazed. Ward says it depends on whether you’ll be growing temperate or tropical plants.

Ward says that, depending on the manufacturer, tempered glass can be wavy like old glass, with kind of a funhouse effect. Experts don’t always agree on whether the glass should be single- or double-glazed. Ward says it depends on whether you’ll be growing temperate or tropical plants.

Shade: In southern locations and depending on the structure’s orientation, glass is sometimes tinted or whitewashed all or part of the year. Shadecloth is another alternative. Tall plants can help shade smaller ones.

Supports: Museum houses usually replace the original material. At Hearst Castle, epoxy and reshaping allowed a restoration crew to rescue about 95 percent of one greenhouse’s original wood supports. It would have been easier to mill new pieces, says project leader Bruce Jackson. A homeowner would be hard pressed to put that much time and money into it.

Rusty cast-iron supports can be cleaned and galvanized. If any are missing, you can sometimes find original drawings and have parts recast. The New York Botanical Garden has a wealth of Lord & Burnham plans, as does Under Glass in Lake Katrine, New York, which took over the manufacture of that company’s greenhouses. An aluminum extrusion is a less expensive alternative.

The New York Botanical Garden has a wealth of Lord & Burnham plans, as does Under Glass in Lake Katrine, New York, which took over the manufacture of that company’s greenhouses. An aluminum extrusion is a less expensive alternative.

Among suppliers of greenhouses and conservatories, many are distributors of structures designed and built in England. Says Smith, “They’ve been doing this for 200 years, and we’ve spent just the last 20 trying to catch up.”

With the recent flurry of high-visibility restorations and increased sales, however, he believes glasshouses may be on the cusp of a huge renaissance. He notes that Lord & Burnham built its famous Irvington, New York, foundry in 1895. “We’ve passed the hundred year mark. I think we’re going through a second wave.”

Conservatory ideas and designs | House & Garden

Gardens

Whether you are hunting for conservatory design ideas, or just want to gaze longingly at glass houses, get inspired by these stylish structures.

By Emily Senior

In the past, the word ‘conservatory’ has not always conjured the most desirable images to mind. Many of us are instantly transported by it to ill-advised and out-of-character additions to otherwise beautiful houses, or to the depths of morbid suburbia, where we dread being subjected to lukewarm gin and tonics and stale conversation. In all, the imagined conservatory is not a place whose reputation necessarily brims with generosity or good cheer.

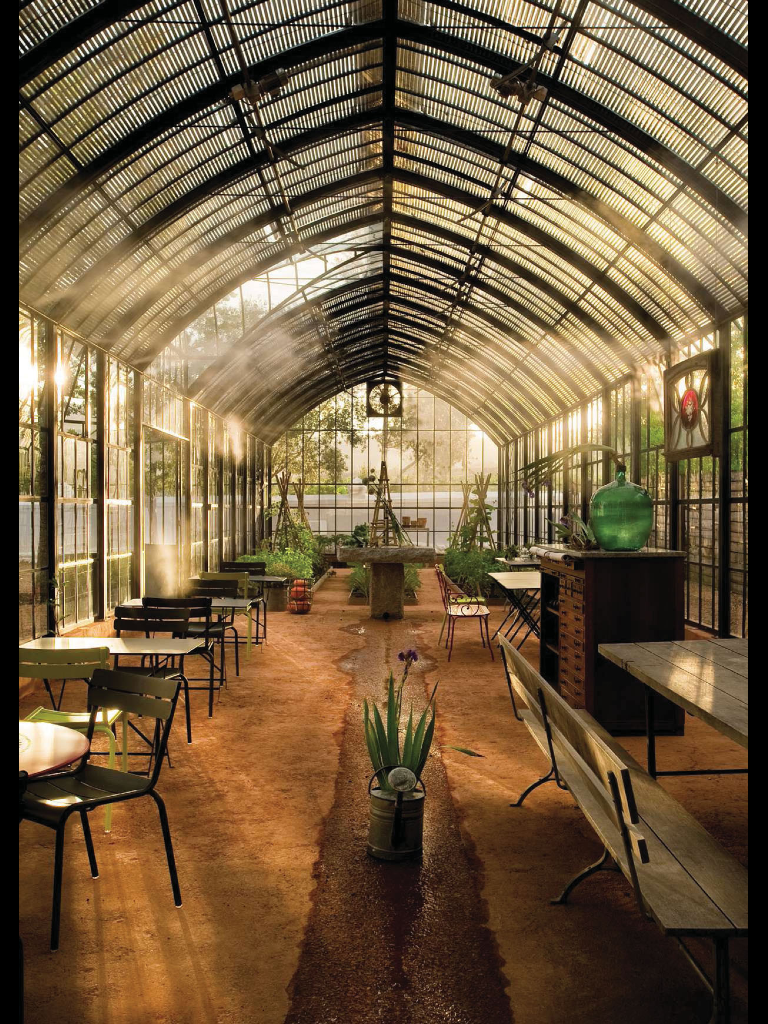

So: conservatories have a bad reputation after years of misuse, but we’re here to bring them back into the spotlight. A conservatory or greenhouse offers a way to feel like you’re experiencing the outdoors – even when the weather isn’t up to scratch – and for making the most of any sunshine on a chill winter’s day. They can be highly atmospheric, too: just imagine sitting under the glass, warm and sheltered, perhaps with a glass of wine or even a single malt, while it rains heavily outside. It’s a deeply calming experience.

It’s a deeply calming experience.

Here, our deputy editor David Nicholls discusses the art of designing and decorating a conservatory with designer Guy Goodfellow.

Why you should fall back in love with the conservatory

One of the most beautiful spaces I have ever been in is an extraordinary Victorian conservatory belonging to a client in Warwickshire,’ Guy explains. ‘It was a winter garden, which we filled with tall trees and enormous, colourful parasols.’ Guy is an architectural and interior designer well versed in the language and nuance of English classicism. No stranger to projects in the country, he is the perfect sounding board for advice on making a conservatory as lovely as it ought to be. One of his all-time favourites has a starring role in the 1990 rom-com film Green Card, in which Andie MacDowell’s character’s rooftop apartment has a lush, palm-filled conservatory complete with a fountain and bamboo furniture.

'And I designed an orangery in Sussex a few years ago,’ Guy continues. ‘It has a huge French chimneypiece with a dining table that extends to seat large numbers.’ Guy loves putting fireplaces in these structures: ‘It gives focus to a room.’ (And in case you are wondering, the main differences between a conservatory and orangery are the glass-to-frame ratio and the shape of the roof.)

‘It has a huge French chimneypiece with a dining table that extends to seat large numbers.’ Guy loves putting fireplaces in these structures: ‘It gives focus to a room.’ (And in case you are wondering, the main differences between a conservatory and orangery are the glass-to-frame ratio and the shape of the roof.)

‘For me, the joy of decorating a house is in creating different areas, each of which has its own atmosphere,’ Guy says. A conservatory should not be thought of as just another sitting room. ‘I think they make wonderful places to dine,’ he adds. ‘You don’t have to have rattan or whatever is perceived as conservatory furniture, but it shouldn’t be filled with duplicates from another room.’

Traditionally, these spaces were inhabited during the day rather than in the evening. All the glass can become ominously black at night, and there is increasing concern about light pollution caused by electric light beaming into the stratosphere. However, in the daytime, plenty of glass means plenty of sunlight, which was, of course, the original purpose of these rooms. If you wish to reduce the amount of light coming into a fully glazed conservatory, Guy advises caution. ‘Curtains would kill it, but you can use the lightest possible blinds. We use ‘Sang Sacre Tristan’ linen by the Irish fabric house Alton-Brooke all the time – it has the most beautiful warp and weft.’

If you wish to reduce the amount of light coming into a fully glazed conservatory, Guy advises caution. ‘Curtains would kill it, but you can use the lightest possible blinds. We use ‘Sang Sacre Tristan’ linen by the Irish fabric house Alton-Brooke all the time – it has the most beautiful warp and weft.’

Conservatory specialists

- David Salisbury

- Malbrook

- Marston & Langinger by Alitex

- Oakwrights

- Prime Oak

- Rhino Greenhouses

- Vale Garden Houses

- Westbury Garden Rooms

We've rounded up our favourite conservatory styles from our archives, so you can be inspired to set up your very own room with a view.

Davide Lovatti

Native ShareThis double-height, steel-framed glasshouse built within the old castle walls of Castello di Reschio serves as a glamorous, light-filled seating area.

- Native Share

This stylish painted orangery in Rutland by Vale Garden Houses features full-length timber and lead panels, neoclassical columns and entablature and an inset glazed roof.

Used by the owners as a living and dining area, the orangery provides access to the garden through multiple sets of doors which can be left open during warmer seasons, or left closed to enjoy views of the garden all year round.

Used by the owners as a living and dining area, the orangery provides access to the garden through multiple sets of doors which can be left open during warmer seasons, or left closed to enjoy views of the garden all year round. - Native Share

Though an orangery or garden room is traditionally joined to a house, having a free-standing design positioned deeper into the garden is a clever way to add indoor space that feels integrated with nature. For this walled garden in Wales, the specialist David Salisbury designed a structure that echoes the garden’s extensive stone works and the architecture of the main house, constructed from local stone with hardwood frames.

- Native Share

Besides the obvious advantages of providing extra living space, an oak-framed extension can also add character and charm to the exterior of your home. Using different materials can create architectural contrast and add layers to a building – imagine an oak extension against beautifully aged stone or red brick, as seen in this Cheshire farmhouse.

The design team at Oakwrights opted for symmetry by placing the oak trusses centrally with double doors leading out to a patio.

The design team at Oakwrights opted for symmetry by placing the oak trusses centrally with double doors leading out to a patio.

Paul Massey

Native ShareThe search for a London pied-à-terre brought Ben Pentreath’s clients unexpectedly to this Georgian house, which he has reconfigured and decorated in his layered signature style. A steel-framed conservatory by Serres d’Antan contains rattan ‘Wengler’ chairs from Sika-Design and a vintage linen table runner. A large Georgian cupboard from Alexander von Westenholz holds gardening equipment.

Simon Brown

Native ShareGarden designer Butter Wakefield and her now ex-husband bought this London Victorian villa in 1991. She described the original kitchen as 'so poky, you could barely open the oven.' But she was able to see the potential when she saw the light 'pouring in across the west-facing garden.' This elegant conservatory was added 10 years ago. The green, black and white palette runs throughout the house but is most prominent in the conservatory and kitchen, where there is a cornucopia of lettuceware plates and monochromatic fabrics.

A smart green window seat is luxuriously heated by the radiator below and is the perfect spot from which to contemplate the garden.

A smart green window seat is luxuriously heated by the radiator below and is the perfect spot from which to contemplate the garden.Lucas Allen

Native ShareDesigner Henri Fitzwilliam-Lay, the owner of this Victorian country house in Shropshire has enhanced the interiors of this grand property with her signature mid-century aesthetic without compromising original features. The conservatory attached to the side of the house provides a bright space. It is decorated with a neutral palette for a calming atmosphere, and striped wallpaper emphasises the height of the space.

- Native Share

Kate Aslangul of Oakley Moore designed this conservatory in Paris. The mosaic tiles are original the house previously hidden underneath a carpet. They feature a white and green hexagonal pattern surrounded by a deep border with accents of coral and yellow tiles, complemented by the green paint on the woodwork. Kate chose a Gilles Nouailhac sofa, upholstered in Pierre Frey’s moss green velvet from the India Mahdavi collection, with GPJ Baker’s Orinoco fabric cushions using only the pineapple section of the design.

A pair of yellow glass table lamps from Porta Romana were chosen together with Julian Chichester’s side tables, inspired by a 1940s French design. The Rococo-style settee was a lucky internet find that Kate had hand-finished and stained by a furniture restorer, later upholstering it in Zak and Fox’s Khotan’s fabric trimmed with double piping from Turnell & Gigon.

A pair of yellow glass table lamps from Porta Romana were chosen together with Julian Chichester’s side tables, inspired by a 1940s French design. The Rococo-style settee was a lucky internet find that Kate had hand-finished and stained by a furniture restorer, later upholstering it in Zak and Fox’s Khotan’s fabric trimmed with double piping from Turnell & Gigon.

Most Popular

Simon Brown

Native ShareThis is a modern take on a conservatory by Philip Hooper, who added a clerestory, supported by a steel frame, to let more light into the dining room.

Lucas Allen

Native ShareTo restore a feeling of equilibrium to his Queen Anne house in Herefordshire, interior decorator Edward Bulmer remodelled the layout, added a new wing, and painted the walls in interesting colours to create a contemporary family home. The kitchen's eating area is housed in the conservatory, part of the newly built wing.

Paul Massey

Native ShareThe architect owners of this handsome 18th-century former weaver’s cottage in Wiltshire added a glass and steel kitchen extension to flood the area with light and connect the space to the outdoors. Its position against an exterior limestone wall combined with a timber-framed roof and the owner’s painstaking process of sourcing salvaged objects helps the structure blend in with the existing architecture.

Elsa Young

Native ShareThe owners added this generous conservatory at the back of their London house (with interior design by Suzy Hoodless), featuring three sets of french windows. Muuto ‘Nerd’ chairs expand the palette and a monochrome rug helps tie the look together.

Most Popular

Simon Brown

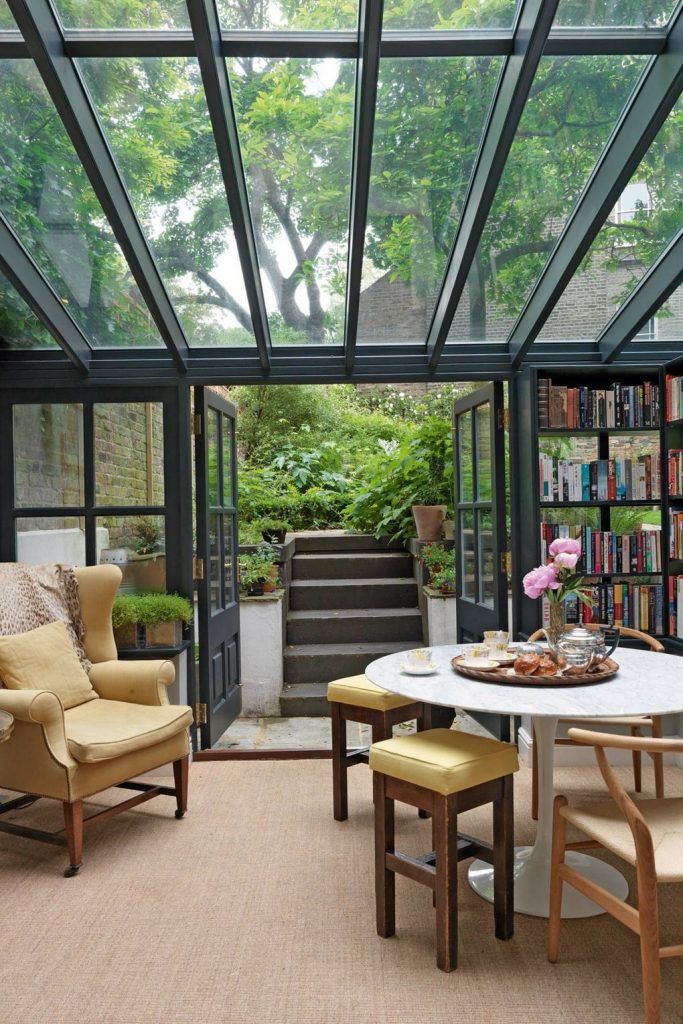

Native ShareThe conservatory in artist and designer Bridie Hall's north London town house is used as a library and snug. Bookcases painted in Farrow & Ball's 'Off Black' lend it a cosy atmosphere.

Taken from the March 2014 issue of House & Garden. Additional text: Liz Elliot.Michael Sinclair

Native ShareA conservatory with rattan furniture and chic blinds acts as an extension of the garden in the London home of Lady Wakefield. The garden room, by Marston & Langinger, also provides an alternative dining area. Like the rest of the house, it is full of pieces chosen with confidence. Nothing is matching and objects are not necessarily of value, but they are all things of beauty and interest.

Paul Massey

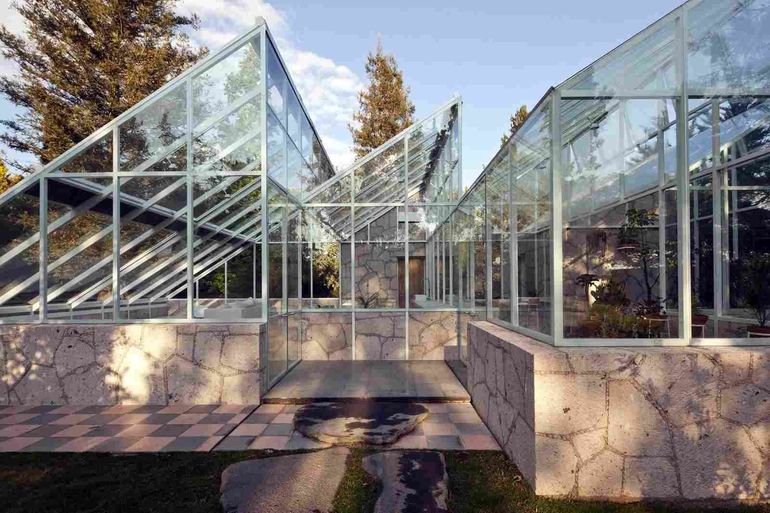

Native ShareA warm welcoming interior with a carefully curated mix of vintage and custom-made furniture gives Ett Hem in Stockholm, designed by Ilse Crawford, the feel of a well-loved house, rather than a hotel. In the glass house, a gauzy sail-like shade can be pulled over the roof to keep out the sun, while an abundance of homely plants links the space to the garden beyond.

- Native Share

Inside the glass and timber extension of this Christopher-Howe-designed house in Bray, the floor is made from cheeseboards, which were found on a trip to the South of France.

Fifties Italian bar stools contrast with the island, which was salvaged from a fishmonger’s.

Fifties Italian bar stools contrast with the island, which was salvaged from a fishmonger’s.

Most Popular

- Native Share

This design is inspired by Hardwick Hall, a sixteenth-century property in Derbyshire. It was designed by Robert Smythson for one of Elizabethan England's most powerful and wealthy women, Bess of Hardwick.

The Hardwick, by The National Trust conservatory collection at Vale Garden Houses - Native Share

A conservatory can add a wonderful space to relax and entertain in. A mix of botanical prints, a patterned tiled floor and natural materials create a look that brings the outside in.

FURNITURE Aluminium side table, 60 x 40cm diameter, and armchair, 87 x 61 x 56cm, £3,000 for a set of two chairs and a table, from Talisman. Rattan cafe armchair, 'Cezanne' (natural leaf and black), 102 x 62 x 61cm, £199, from Drucker. Zinc-topped oak table, 'Sawbuck', 76 x 304 x 78cm, £4,140, from Matthew Cox.

Rattan and plastic outdoor side chair, 'Isabell' (black and white), by Sika Design, 92 x 48 x 59cm, £180, from Designers Guild.

Rattan and plastic outdoor side chair, 'Isabell' (black and white), by Sika Design, 92 x 48 x 59cm, £180, from Designers Guild.ACCESSORIES Ceramic lamp base, 'Sibyl' (spinach), £516, from Porta Romana; with antique silk shade, £600, from Guinevere. Porcelain side plate (on side table), 'Dahlia', e9, from Virebent. Cushions, from top: 'Moss' (charcoal), by Howard Hodgkin, cotton, £110 a metre, from Designers Guild. 'Aylsham' (L-219), cotton, £96 a metre, from Fermoie. Wicker-basket pendant lights, 40 x 56cm diameter, £130 each, from Original House. Fabric (under plant stands), 'Tuileries' (crème), by Verel de Belval, linen/polyester, £238 a metre, from Abbott & Boyd. Porcelain bowls (yellow), by Mud Australia, from £45 each; napkins, 'Leaf' (charcoal), by Howard Hodgkin, cotton, £110 a metre; tablecloth, 'Brush' (charcoal), by Howard Hodgkin, cotton, £110 a metre. All from Designers Guild. White stoneware, 'Cracked Slip Vase', by Matthias Kaiser, £200, from The Garden Edit.

Chinese glazed yellow stoneware,'Lantern Jars', £800 each; Han dynasty stoneware Hu vase, £1,450; indigo-dyedlinen sheet (on chair), £360. All from Guinevere. Ceramic parrot incense holder, £98, from Plümo. Resin plate, 'Black and Snow Swirl', £120, from Dinosaur Designs.

Chinese glazed yellow stoneware,'Lantern Jars', £800 each; Han dynasty stoneware Hu vase, £1,450; indigo-dyedlinen sheet (on chair), £360. All from Guinevere. Ceramic parrot incense holder, £98, from Plümo. Resin plate, 'Black and Snow Swirl', £120, from Dinosaur Designs. Line T Klein

Native ShareVictorian meets twenty-first century: original tiling is complemented by white furniture with clean lines in this Georgian orangery at a Somerset country house. This elegantly curved orangery was updated by the Victorian owners and now houses one of two kitchens.

- Native Share

Lantern roofs may have originally been devised for orangeries, but the possibilities are endless (a kitchen is one option we find immensely appealing) - especially for colour. This bespoke structure in London is painted in 'sage' from Marston & Langinger's Exterior Eggshell range.

Most Popular

David Oliver

Native ShareIn this Norfolk country home, interior decorator Veere Grenney wanted to respect the architecture of the rooms yet reflect the owners' relaxed and hospitable way of life.

A long table can be found in the relatively new conservatory, which links the Georgian part of the house to the Tudor wing. This 'Waste Table' in plywood was made by Piet Hein Eek and is surrounded by Hans J Wegner 'Wishbone' chairs. Above it, hanging from an oculus in the ceiling, is a Charles Saunders 'Oak Leaf' chandelier, which could be an armful of foliage blown in from the park.

A long table can be found in the relatively new conservatory, which links the Georgian part of the house to the Tudor wing. This 'Waste Table' in plywood was made by Piet Hein Eek and is surrounded by Hans J Wegner 'Wishbone' chairs. Above it, hanging from an oculus in the ceiling, is a Charles Saunders 'Oak Leaf' chandelier, which could be an armful of foliage blown in from the park.Simon Brown

Native ShareThe owners of this Victorian townhouse in west London have decorated the classically proportioned rooms in plain and simple finishes to create the perfect setting in which to display their collection of modern design.

In the kitchen architect Seth Stein has tweaked the existing conservatory giving it a more graceful roofline and adding smart bronze details to the doors opening on to the garden. 'The idea of the client was to treat the place like a kind of installation,' he explains. Artist Stuart Haygarth recycled plastic flotsam and jetsome to create a shimmering chandelier, Tide, suspended above the dining table. The dining table and eighteen chairs are by India Mahdavi.

The dining table and eighteen chairs are by India Mahdavi.Alex James

Native ShareChristopher Mitchell of Hill Mitchell Berry Architects and the interior design Charlotte Lane Fox have added a sense of light and space to the lower ground floor of this elegant Kensington house with the addition of a conservatory extension that leads out in to the garden.

Jan Baldwin

Native ShareInterior designer Chester Jones complemented the mosaic floor in the kitchen to the courtyard outside.

Most Popular

- Native Share

This glorious garden room in Surrey was a bespoke creation from Marston & Langinger, right down to the paint (granite) and the furniture inside.

Simon Brown

Native ShareThe airy conservatory at Ballyfin was added by Richard Turner around 1855. It is a very grand structure that could serve as a nursery for seedlings as well as a breakfast room.

TopicsGardens

Read MoreGlass Flower: Heatherwick Studio UK

Architecture

Heatherwick Studio and the National Trust (UK) have opened a kinetic greenhouse in Woolbeding Gardens. It marked the final planning point for the new Silk Road Garden, designed to commemorate the influence of the medieval route on modern British horticulture. Rare goods and new plant species such as rosemary, lavender and fennel arrived in the UK along this route. The path takes visitors through the 300 plant species planted in the Silk Road Garden and ends at the new greenhouse. nine0003

It marked the final planning point for the new Silk Road Garden, designed to commemorate the influence of the medieval route on modern British horticulture. Rare goods and new plant species such as rosemary, lavender and fennel arrived in the UK along this route. The path takes visitors through the 300 plant species planted in the Silk Road Garden and ends at the new greenhouse. nine0003

Greenhouse with open glass panels - "petals".

- Photo

- Raquel Diniz

The greenhouse consists of ten steel components that support the corner glass panels, resembling a flower bud that opens with daylight. On warm days, the "petals" open to form a crown-shaped space. The opening of the glass panels uses a hydraulic mechanism developed by the studio in collaboration with engineers from Eckersley O'Callaghan. nine0003

According to Thomas Heatherwick, the design of the conservatory refers to decorative Victorian terrariums, airtight glass containers in which plants were placed.

- Photo

- Hufton + Crow

The opening process takes four minutes and is designed to provide subtropical plants with sufficient light and air in warm weather. As soon as the temperature outside the greenhouse falls below the permissible level, the glass "petals" are closed, saving the plants from the cold. ventilation. nine0003

Top view of the open greenhouse with subtropical plants.

- Photo

- Hufton + Crow

View of the Woolbeding Gardens and the small Silk Road Garden with the new greenhouse.

- Photo

- Hufton + Crow

“You walk through a mesmerizingly beautiful garden and discover an object that starts like a jewel and ends like a crown as the conservatory slowly opens up,” said studio founder Thomas Heatherwick of the new work. Heatherwick). nine0003

Heatherwick). nine0003

When closed, the greenhouse resembles not only a flower bud, but also a cut diamond, its facets shimmering in the sun.

- Photo

- Hufton + Crow

Subtropical plants, once brought to Great Britain along the Silk Road, are planted inside the greenhouse. Including rare Vietnamese aralia, various ferns, umbrella trees, magnolias and bananas.

Fern, banana, magnolias and Vietnamese aralia planted inside the greenhouse. nine0003

- Photo

- Hufton + Crow

Elena Igumnova

Tags

- UK

- Europe 2

- clay;

- straw;

- tree;

- granite;

- sand.

- bedrooms for children and parents;

- spacious living room;

- kitchen;

- two bathrooms.

Home Home Environmental project in Sweden: amazing greenhouse house

Environmentally friendly houses have recently become extremely popular all over the world. But most often these are just ideas that are rarely implemented so far. However, quite recently, a delightful greenhouse house was built in Sweden according to the project of the famous architect Bengt Varna. nine0003

But most often these are just ideas that are rarely implemented so far. However, quite recently, a delightful greenhouse house was built in Sweden according to the project of the famous architect Bengt Varna. nine0003

Project Description Bengta Varna

An ecological house project in Sweden called Uppgrenna Nature House. It was realized by the well-known European architect Bengt Warn , working in the studio Tailor Made Arkitekter. The house was built on the shores of the Swedish lake Vättern. The basis for it was the premises of an ordinary barn, where the grain harvest and other products are usually stored.

The designer came up with the idea to turn the building into a greenhouse after seeing its shape. nine0003

During construction, some of the structures were replaced, but the exterior of the house remained the same. It has two floors, the dwelling itself is inside a thick glass frame, the roof is completely made of glass so that the room receives natural light. Inside there is a botanical garden where exotic plants grow. This building is not intended for habitation. Now it houses a spa center, where visitors not only do cosmetic procedures, but also have a pleasant rest in nature with a cup of tea with fragrant lemon. nine0003

Inside there is a botanical garden where exotic plants grow. This building is not intended for habitation. Now it houses a spa center, where visitors not only do cosmetic procedures, but also have a pleasant rest in nature with a cup of tea with fragrant lemon. nine0003

House-greenhouse of the Swedish spouses

Based on the project of the designer Varna, the couple from Stockholm, Marie Granmar and Charles Sasilotto, created a house-hothouse for housing from an old dacha, having spent about 85 thousand dollars on reconstruction. The aluminum frame around the house is covered with 4 mm thick glass , which ensures a mild Mediterranean climate indoors. It's cold outside, but inside the building it's 20 degrees Celsius. This is not only a picturesque natural corner right in the house, but also savings on heating, as well as independent sewerage. nine0003

The couple made a centrifugal wastewater treatment plant in their home to separate urine from feces. The purified liquid mass is used for watering vegetables and trees. Greenhouse conditions prolong the fruiting period of plants. The couple not only grow vegetables, berries and fruits traditional for their area, but also always have fresh lemons, figs and watermelons on the table.

The purified liquid mass is used for watering vegetables and trees. Greenhouse conditions prolong the fruiting period of plants. The couple not only grow vegetables, berries and fruits traditional for their area, but also always have fresh lemons, figs and watermelons on the table.

The house has several terraces, including on the roof, where solar panels are installed to save energy. Living rooms, like in a regular house, are quite spacious and comfortable. nine0003

Glass dome dwelling

Although several houses were built according to the Varna project in Sweden and Germany, this idea was soon forgotten. But a few years ago, the Tailor Made studio remembered it and even built an exhibition hall to order, covering one of the Swedish buildings with a glass dome. Above the Arctic Circle in Norway, neighboring Sweden, the large Gjertefolger family built housing under a dome. Natural materials were used for the construction of the building:

Natural materials were used for the construction of the building:

The structure resembles a adobe and outwardly primitive hut, which is easily destroyed by the elements of nature, but this impression is erroneous. From above, the building is covered with a dome of glass cells, which are fixed on wooden beams. The couple arranged a garden and a kitchen garden between the house and the glass, providing the family with vegetables and herbs all year round. Inside is very warm and cozy. nine0086 The building has:

Solar batteries provide housing with energy, there is sewerage. When the family was building the house, the Swedish architect was no longer alive, so he could not admire the realization of his idea.