16Th century homes

A History of Homes - Local Histories

By Tim Lambert

Celtic HomesThe Celts lived in roundhouses. They were built around a central pole with horizontal poles radiating outwards from it. They rested on vertical poles. Walls were of wattle and daub and roofs were thatched. Around the walls inside the huts were benches, which also doubled up as beds. The Celts also used low tables.

Roman HomesAfter the Roman Conquest, upper-class Celts adopted the Roman way of life. They built villas modeled on Roman buildings and they enjoyed luxuries such as mosaics and even a form of central heating called a hypocaust. Wealthy Romans also had wall paintings called murals in their houses. In their windows, they had panes of glass. Of course, poorer Romans had none of these things. Their houses were simple and plain and the main form of heating was braziers.

For the wealthy furniture was very comfortable. It was upholstered and finely carved. People ate while reclining on couches. Oil lamps were used for light. Furthermore, some people had a piped water supply. Water was brought into towns in aqueducts that went along lead pipes to individual houses. However Roman rule probably made little difference to most poor Celts, especially in the north and extreme southwest of England. For them, life went on much as it had before. Their houses remained simple huts.

Life was hard in Anglo-Saxon times and homes were rough. There were no panes of glass in windows, even in a thane’s (noble’s) hall and there were no chimneys. Floors were of earth or sometimes they were dug out and had wooden floorboards placed over them. There were no carpets. n Rich people’s houses were rough, crowded, and uncomfortable. Even a thanes hall was really just a large wooden hut although it was usually hung with rich tapestries. Thanes also like to show off any furniture they owned. Any furniture must have been simple and heavy such as wooden chests.

Peasant homes were simple wooden huts. They had wooden frames filled in with wattle and daub (strips of wood woven together and covered in a ‘plaster’ of animal hair and clay). However, in some parts of the country huts were made of stone. Peasant huts were either whitewashed or painted in bright colors. The poorest people lived in one-room huts. Slightly better-off peasants lived in huts with one or two rooms. There were no panes of glass in the windows only wooden shutters, which were closed at night. The floors were of hard earth sometimes covered in straw for warmth.

In the middle of a Medieval peasant’s hut was a fire used for cooking and heating. There was no chimney. Any furniture was very basic. Chairs were very expensive and no peasant could afford one. Instead, they sat on benches or stools. They would have a simple wooden table and chests for storing clothes and other valuables. Tools and pottery vessels were hung on hooks. The peasants slept on straw and they did not have pillows. Instead, they rested their heads on wooden logs.

The peasants slept on straw and they did not have pillows. Instead, they rested their heads on wooden logs.

The peasant’s wife cooked on a cauldron suspended over the fire and the family ate from wooden bowls. Candles were expensive so peasants usually used rushlights (rushes dipped in animal fat). At night in summer and all day in winter the peasants shared their huts with their animals. Parts of it were screened off for the livestock. Their body heat helped to keep the hut warm.

Rich People’s Houses In The Middle AgesThe Normans, at first, built castles of wood. In the early 12th century stone replaced them. In the towns, wealthy merchants began living in stone houses. (The first ordinary people to live in stone houses were Jews. They had to live in stone houses for safety).

In Saxon times a rich man and his entire household lived together in one great hall. In the Middle Ages, the great hall was still the center of a castle but the lord had his own room above it. This room was called the solar. In it, the lord slept in a bed, which was surrounded by curtains, both for privacy and to keep out drafts. The other members of the lord’s household, such as his servants, slept on the floor of the great hall. At one or both ends of the great hall, there was a fireplace and chimney.

This room was called the solar. In it, the lord slept in a bed, which was surrounded by curtains, both for privacy and to keep out drafts. The other members of the lord’s household, such as his servants, slept on the floor of the great hall. At one or both ends of the great hall, there was a fireplace and chimney.

In the Middle Ages, chimneys were a luxury. As time passed they became more common but only a small minority could afford them. Certainly, no peasant could afford one.

About 1180 for the first time since the Romans rich people had panes of glass in the windows. At first, glass was very expensive and only rich people could afford it but by the late 13th and early 14th centuries, the middle classes began to have glass in some of their windows. Those people who could not afford glass could use thin strips of horn or pieces of linen soaked in tallow or resin which were translucent.

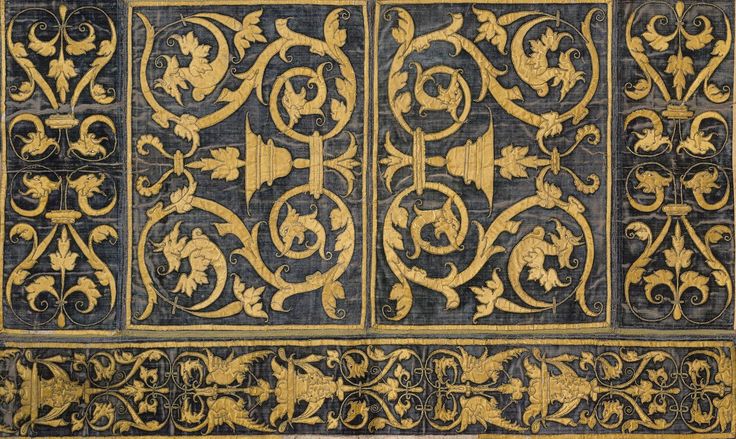

Furniture in the Middle Ages was very basic. Even in a rich household chairs were rare. Most people sat on stools or benches. Rich people also had tables and large chests, which doubled up as beds. Rich people’s homes were hung with wool tapestries or painted linen. They were not just for decoration. They also helped keep out drafts. In a castle, the toilet or garderobe was a chute built into the thickness of the wall. The seat was made of stone. Sometimes the garderobe emptied straight into the moat!

Most people sat on stools or benches. Rich people also had tables and large chests, which doubled up as beds. Rich people’s homes were hung with wool tapestries or painted linen. They were not just for decoration. They also helped keep out drafts. In a castle, the toilet or garderobe was a chute built into the thickness of the wall. The seat was made of stone. Sometimes the garderobe emptied straight into the moat!

In the Middle Ages, rich people’s houses were designed for defense rather than comfort. In the 16th century, life was safer so houses no longer had to be easy to defend. It was an age when rich people built grand houses e.g. Cardinal Wolsey built Hampton Court Palace. Late the Countess of Shrewsbury built Hardwick Hall in Derbyshire.

People below the rich but above the poor built sturdy ‘half-timbered’ houses. They were made with a timber frame filled in with wattle and daub (wickerwork and plaster). In the late 16th century some people built or rebuilt their houses with wooden frames filled in with bricks. Roofs were usually thatched though some well-off people had tiles. (In London all houses had tiles because of the fear of fire).

Roofs were usually thatched though some well-off people had tiles. (In London all houses had tiles because of the fear of fire).

Furniture was more plentiful in the 16th century than in the Middle Ages but it was still basic. In a wealthy home, it was usually made of oak and was heavy and massive. Tudor furniture was expected to last for generations. You expected to pass it on to your children and even your grandchildren. Comfortable beds became more and more common in the 16th century and increasing numbers of middle-class people slept on feather mattresses rather than straw ones. Chairs were more common than in the Middle Ages but they were still expensive. Even in upper-class homes children and servants sat on stools. The poor had to make do with stools and benches.

In the 15th century, only a small minority of people could afford glass windows. During the 16th century, they became much more common. However, they were still expensive. If you moved house you took your glass windows with you! Tudor windows were made of small pieces of glass held together by strips of lead. They were called lattice windows. However the poor still had to make do with strips of linen soaked in linseed oil. Chimneys were also a luxury in the 16th century, although they became more common.

They were called lattice windows. However the poor still had to make do with strips of linen soaked in linseed oil. Chimneys were also a luxury in the 16th century, although they became more common.

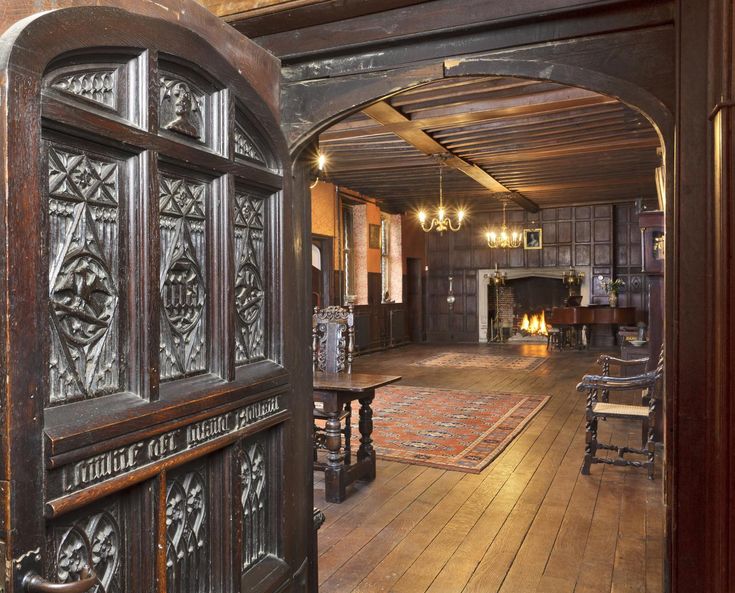

Furthermore, in the Middle Ages, a well-to-do person’s house was dominated by the great hall. In the 16th century, well-off people’s houses became divided into more rooms.

In wealthy Tudor houses, the walls of rooms were lined with oak panelling to keep out drafts. People slept in four-poster beds hung with curtains to reduce drafts. In the 16th century, some people had wallpaper but it was very expensive. Other wealthy people hung tapestries or painted cloths on their walls. In the 16th century carpets were a luxury only the richest people could afford. They were usually too expensive to put on the floor! Instead, they were often hung on the wall or over tables. People covered the floors with rushes or reeds (or mats of woven reeds or rushes) which they strewed with sweet-smelling herbs.

In the 16th century, prosperous people lit their homes with beeswax candles. However, they were expensive. Others made used candles made from tallow (animal fat) which gave off an unpleasant smell and the poorest people made do with rushlights (rushes dipped in animal fat).

In the 16th century, the rich had clocks in their homes. The rich had pocket watches although most people relied on pocket sundials. Rich Tudors were also fond of gardens. Many had mazes, fountains, and topiary (hedges cut into shapes). Less well-off people used their gardens to grow vegetables and herbs.

Tudor housesNone of the improvements of the 16th century applied to the poor. They continued to live in simple huts with one or two rooms (occasionally three). Smoke escaped through a hole in the thatched roof. Floors were of hard earth and furniture was very basic, benches, stools, a table, and wooden chests. They slept on mattresses stuffed with straw or thistledown. The mattresses lay on ropes strung across a wooden frame.

In 1596 Sir John Harrington invented a flushing lavatory with a cistern. However, the idea failed to catch on. People continued to use chamber pots or cesspits, which were cleaned by men called gong farmers. (In the 16th century a toilet was called jakes).

Rich 17th Century People’s HomesIn the late 17th century furniture for the wealthy became more comfortable and much more finely decorated. In the early 17th century furniture was plain and heavy. It was usually made of oak. In the late 17th century furniture for the rich was often made of walnut or (from the 1680s) mahogany. It was decorated in new ways. One was veneering. (Thin pieces of expensive wood were laid over cheaper wood). Some furniture was also inlaid. Wood was carved out and the hollow was filled in with mother of pearl. At this time lacquering arrived in England. Pieces of furniture were coated with lacquer in bright colors.

Furthermore, new types of furniture were introduced. In the mid-17th century chests of drawers became common. Grandfather clocks also became popular. Later in the century, the bookcase was introduced. Chairs also became far more comfortable. Upholstered (padded and covered) chairs became common in wealthy people’s homes. In the 1680s the first real armchairs appeared.

In the mid-17th century chests of drawers became common. Grandfather clocks also became popular. Later in the century, the bookcase was introduced. Chairs also became far more comfortable. Upholstered (padded and covered) chairs became common in wealthy people’s homes. In the 1680s the first real armchairs appeared.

In the early 17th century the architect Inigo Jones introduced the classical style of architecture (based on ancient Greek and Roman styles). He designed the Banqueting Hall in Whitehall, which was the first purely classical building in England. The late 17th century was a great age for building grand country homes, displaying the wealth of the upper class at that time.

Poor People’s Homes in the 17th CenturyHowever, all the improvements in furniture did not apply to the poor. Their furniture remained very plain and basic. However, there were some improvements in poor people’s houses in the 17th century. In the Middle Ages, ordinary people’s homes were usually made of wood. However in the late 16th and early 17th centuries, many were built or rebuilt in stone or brick. By the late 17th century even poor people usually lived in houses made of brick or stone. They were a big improvement over wooden houses. They were warmer and drier.

However in the late 16th and early 17th centuries, many were built or rebuilt in stone or brick. By the late 17th century even poor people usually lived in houses made of brick or stone. They were a big improvement over wooden houses. They were warmer and drier.

In the 16th century chimneys were a luxury. However, during the 17th century chimneys became more common and by the late 17th century even the poor had them. Furthermore in 1600 glass windows were a luxury. Poor people made do with linen soaked in linseed oil. However, during the 17th century glass became cheaper and by the late 17th century even the poor had glass windows.

In the early 17th century there were only casement windows (ones that open on hinges). In the later 17th century sash windows were introduced. They were in two sections and they slid up and down vertically to open and shut. Although poor people’s homes improved in some ways they remained very small and crowded. Most of the poor lived in huts of 2 or 3 rooms. Some families lived in just one room.

Some families lived in just one room.

In the 18th century, a small minority of the population lived in luxury. The rich built great country houses. A famous landscape gardener called Lancelot Brown (1715-1783) created beautiful gardens. (He was known as ‘Capability’ Brown from his habit of looking at land and saying it had ‘great capabilities’). The leading architect of the 18th century was Robert Adam (1728-1792). He created a style called neo-classical and he designed many 18th-century country houses.

The wealthy owned comfortable upholstered furniture. They owned beautiful furniture, some of it veneered or inlaid. In the 18th century, much fine furniture was made by Thomas Chippendale (1718-1779), George Hepplewhite (?-1786), and Thomas Sheraton (1751-1806). The famous clockmaker James Cox (1723-1800) made exquisite clocks for the rich.

However the poor had none of these things. Craftsmen and laborers lived in 2 or 3 rooms. The poorest people lived in just one room. Their furniture was very simple and plain.

The poorest people lived in just one room. Their furniture was very simple and plain.

In the 19th century, well-off people in Britain lived in very comfortable houses. (Although their servants lived in cramped quarters, often in the attic). For the first time, furniture was mass-produced. That meant it was cheaper but unfortunately standards of design fell. To us, 19th-century middle-class homes would seem overcrowded with furniture, ornaments, and knick-knacks. However, only a small minority could afford this comfortable lifestyle.

In the early 19th century housing for the poor was dreadful. Often they lived in ‘back-to-backs’. These were houses of three (or sometimes only two) rooms, one on top of the other. The houses were literally back-to-back. The back of one house joined onto the back of another and they only had windows on one side. The bottom room was used as a living room and kitchen. The two rooms upstairs were used as bedrooms.

The worst homes were cellar dwellings. These were one-room cellars. They were damp and poorly ventilated. The poorest people slept on piles of straw because they could not afford beds. Fortunately in the 1840s local councils passed by-laws banning cellar dwellings. They also banned any new back-to-backs. The old ones were gradually demolished and replaced over the following decades.

In the early 19th century skilled workers usually lived in ‘through houses’ i.e. ones that were not joined to the backs of other houses. Usually, they had two rooms downstairs and two upstairs. The downstairs front room was kept for the best. The family kept their best furniture and ornaments in this room. They spent most of their time in the downstairs back room, which served as a kitchen and living room. As the 19th century passed more and more working-class people could afford this lifestyle.

In the USA Augustus Pope patented the first modern burglar alarm in 1853. Melville Bissell invented a carpet sweeper in 1876.

In the late 19th century worker’s houses greatly improved. After 1875 most towns passed building regulations which stated that e.g. new houses must be a certain distance apart, rooms must be of a certain size and windows of a certain size. By the 1880s most working-class people lived in houses with two rooms downstairs and two or even three bedrooms. Most had a small garden. At the end of the 19th century, some houses for skilled workers were built with the latest luxury – an indoor toilet.

Most 19th century homes also had a scullery. In it was a ‘copper’, a metal container for washing clothes. The copper was filled with water and soap powder was added. To wash the clothes they were turned with a wooden tool called a dolly. Or you used a metal plunger with holes in it to push clothes up and down. Wet clothes were wrung through a device called a mangle or wringer to dry them.

At the beginning of the 19th century people cooked over an open fire. This was very wasteful as most of the heat went up the chimney. In the 1820s an iron cooker called a range was introduced. It was a much more efficient way of cooking because most of the heat was contained within. By the mid-19th century ranges were common. Most of them had a boiler behind the coal fire where water was heated.

In the 1820s an iron cooker called a range was introduced. It was a much more efficient way of cooking because most of the heat was contained within. By the mid-19th century ranges were common. Most of them had a boiler behind the coal fire where water was heated.

However, even at the end of the 19th century, there were still many families living in one room. Old houses were sometimes divided up into separate dwellings. Sometimes if windows were broken slum landlords could not or would not replace them. So they were ‘repaired’ with paper. Or rags were stuffed into holes in the glass.

Gaslight first became common in well-off people’s homes in the 1840s. By the late 1870s, most working-class homes had gaslight, at least downstairs. Bedrooms might have oil lamps. Gas fires first became common in the 1880s. Gas cookers first became common in the 1890s. Joseph Swan invented the electric light bulb in 1878. Edison invented an improved version in 1879. However electric light was expensive and it took a long time to replace gas in people’s homes.

In the early 19th century only rich people had bathrooms. People did take baths but only a few people had actual rooms for washing. In the 1870s and 1880s, many middle-class people had bathrooms built. The water was heated by gas. Working-class people had a tin bath and washed in front of the kitchen range.

In the 1890s, for the well-to-do, a new style of art and decoration appeared called Art Nouveau. It involved swirling and flowing lines and stylized plant forms.

20th Century HomesAt the start of the 20th century, working-class homes in Britain had two rooms downstairs. The front room and the back room. The front room was kept for the best and children were not allowed to play there. In the front room, the family kept their best furniture and ornaments. The back room was the kitchen and it was where the family spent most of their time. Most families cooked on a coal-fired stove called a range, which also heated the room.

This lifestyle changed in the early 20th century as gas cookers became common. They did not heat the room so people began to spend most of their time in the front room or living room, by the fire. Rising living standards meant it was possible to furnish all rooms properly not just one.

They did not heat the room so people began to spend most of their time in the front room or living room, by the fire. Rising living standards meant it was possible to furnish all rooms properly not just one.

During the 20th century, ordinary people’s furniture greatly improved in quality and design. In the 1920s and 1930s, a new style of furniture and architecture was introduced. It was called Art Deco and it used geometric shapes instead of the flowing lines of the earlier Art Nouveau. The name art deco came from an exhibition held in Paris in 1925 called the Exposition Internationale des Arts Decoratifs.

At the beginning of the 20th century, only rich people could afford electric light. Other people used gas. Ordinary people did not have electric light until the 1920s and 1930s. In the early 20th century vacuum cleaners and washing machines were available but only rich people could afford them. They became more common in the 1930s, though they were still expensive. By 1959 about two-thirds of British homes had a vacuum cleaner. However, fridges and washing machines did not become really common till the 1960s.

However, fridges and washing machines did not become really common till the 1960s.

The first practical electric fire was made in 1912 but they did not become common until the 1930s. Central heating became common in the 1960s and 1970s. Double glazing became common in the 1980s. Plastic or PVC was first used in the 1940s. By the 1960s all kinds of household goods from drain pipes to combs were made of plastic.

In 1900 about 90% of the population rented their home. However, homeownership became more common during the 20th century. By 1939 about 27% of the population owned their own house.

Meanwhile, the first council houses were built before the First World War. More were built in the 1920s and 1930s and some slum clearance took place. However, council houses remained rare until after World War II. After 1945 many more were built and they became common. In the early 1950s, many homes still did not have bathrooms and only had outside lavatories. The situation greatly improved in the late 1950s and 1960s. Large-scale slum clearance took place when whole swathes of old terraced houses were demolished. High-rise flats replaced some of them.

Large-scale slum clearance took place when whole swathes of old terraced houses were demolished. High-rise flats replaced some of them.

However, flats proved to be unpopular with many people. Some people who lived in the new flats felt isolated. The old terraced houses may have been grim but at least they often had a strong sense of community, which was usually not true of the flats that replaced them. In 1968 a gas explosion wrecked a block of flats at Ronan Point in London and public opinion turned against them. In the 1970s the emphasis turned to renovating old houses rather than replacing them. Then, in 1979 the British government adopted a policy of selling council houses.

Last revised 2022

English Buildings: ...c 1500-1700

This is the second page in a series of brief introductions to the history of English architecture, illustrated with links to posts on this blog. This page deals with the Tudor and Stuart periods - broadly speaking, the 16th and 17th centuries.

Tudor architecture

In 1485 the first Tudor monarch, Henry VII, came to the throne in England. Fifty years later his son, Henry VIII, had broken with Rome, made himself head of the Church in England, and begun the process that would lead to the dissolution of the monasteries in his kingdom. In this new political and religious climate, church building slowed down. On the other hand, many houses were built in this period – the increased wealth of the crown, and especially of the upper classes, made the 16th century a great age of domestic architecture.

The 16th and 17th centuries saw radical changes in English architecture, brought on in the main by two factors – firstly, the influence of the Renaissance, bringing the influence of Classical art and design to Britain; second, the fact that so many buildings were rebuilt in the period, to the extent that historians have spoken about a “Great rebuilding” or “great rebuildings” transforming the country.

The great rebuildings

During around 70 years between 1570 and 1640, improved economic conditions led to thousands of houses being rebuilt – especially in southern England, beginning in the southeast and spreading across the southwest in the latter part of the period. After the upheaval of the English Civil War put the brakes on building in many places, the rebuilding seems to have continued in northern England and Wales after 1670. These dates are approximate and the subject of scholarly debate, but indicate a broad pattern.

The great rebuildings gave many people larger and more solidly constructed houses. Houses that had just a single storey (or one storey plus an attic with dormer windows) frequently acquired a full-height upper storey. Often the extra level was achieved by building a new floor into a single-storey hall house, to divide it in two horizontally. In stone areas, timber-framed houses were often rebuilt in stone; elsewhere, timber frames were renewed. The kind of well made, close studded wooden frame seen at the Saracen’s Head, Kings Norton, built at the end of the 15th century and the beginning of the 16th, is a good example of this kind of Tudor timber-framed structure. The beautiful Paycocke's, Coggeshall, also early-16th century, is, if anything, a still more magnificent example. Glass became more affordable, and windows in houses tended to get larger. Houses that consisted mainly of one big room with a central hearth and a smoke-hole in the roof acquired smaller, more comfortable rooms with proper fireplaces.

The kind of well made, close studded wooden frame seen at the Saracen’s Head, Kings Norton, built at the end of the 15th century and the beginning of the 16th, is a good example of this kind of Tudor timber-framed structure. The beautiful Paycocke's, Coggeshall, also early-16th century, is, if anything, a still more magnificent example. Glass became more affordable, and windows in houses tended to get larger. Houses that consisted mainly of one big room with a central hearth and a smoke-hole in the roof acquired smaller, more comfortable rooms with proper fireplaces.

Many Tudor houses survive, and a lot of them are modest vernacular buildings. In other words, they are built according to local fashion, by local people, using locally available materials – limestone in the Cotswolds, chalk in the Chilterns, timber framing in the Welsh marches, local clay in Devon, and so on. In addition, in some areas where there was no good building stone, a new material, not much used in the Middle Ages, was employed: brick. Although they looked modest from the outside, these buildings were probably brightly decorated within. While wooden panelling and rich tapestries covered the walls of the houses of the rich, some people made do with painted decoration, as seen in a rare surviving painted room in Ledbury, Herefordshire (picture above).

Although they looked modest from the outside, these buildings were probably brightly decorated within. While wooden panelling and rich tapestries covered the walls of the houses of the rich, some people made do with painted decoration, as seen in a rare surviving painted room in Ledbury, Herefordshire (picture above).

These local fashions and ways of building still endure in the places we now think of as “unspoiled” by modern materials and building techniques. They are part of what gives the regions of the country their local distinctiveness. Vernacular architecture was also the mode chosen by the builders of the first nonconformist chapels and meeting houses, the earliest of which date from the Tudor period. Some, like the one at Horningsham, with its thatched roof and plain windows, are easy to mistake for houses at first glance.

This was also a notable period for school foundations – in part to compensate for the educational gap left when the monasteries were dissolved and to lay the foundations of education in the Protestant tradition. Elizabethan grammar schools, like the one at Burford, were often in the vernacular style too.

Elizabethan grammar schools, like the one at Burford, were often in the vernacular style too.

The Tudor style

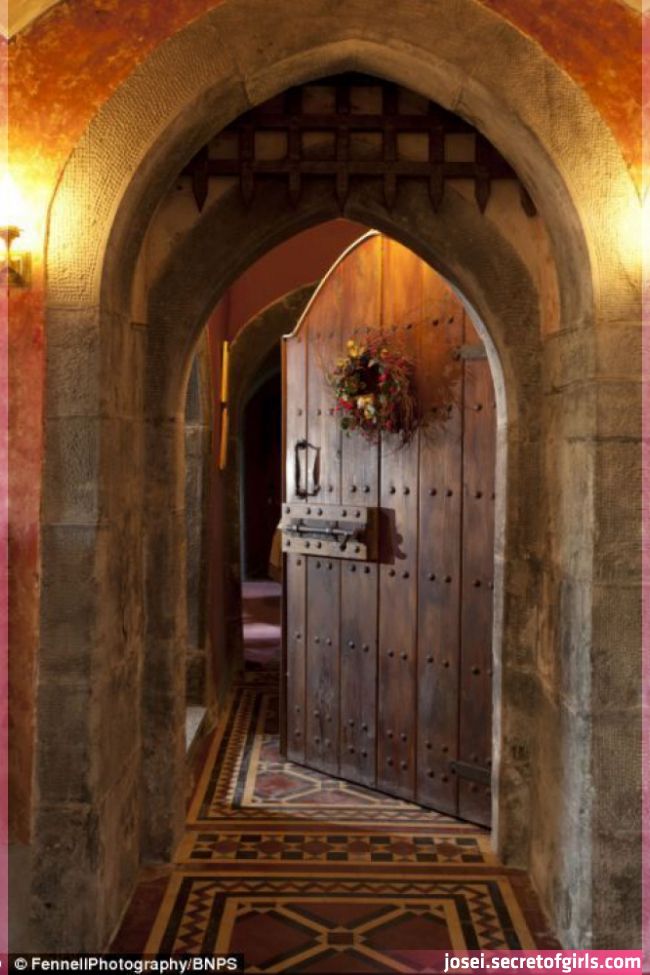

Grander buildings – the houses of the gentry and aristocracy, for example – were built in a more elaborate way. Although their facades could be quite simple, with rows of mullioned windows and perhaps some decoration around the doorway, as at Canons Ashby (picture above), their exteriors were frequently built for show, with really large, mullioned windows, protruding bays and oriels, tall, ornate chimneys, and prominent gables, sometimes curved in the Dutch style. Although the large windows and ornamental features make these houses dramatically different from the buildings of the previous century, elements of that century’s late Gothic style often remain embedded in them – arches and doorways are usually of the flattened, four-centred kind often seen in 15th-century churches, for example. This kind of architecture is seen to perfection in country houses such as Broughton Castle in Oxfordshire and the ornate gatehouse at Coughton Court in Warwickshire, and the many-windowed facades of Stanway House in Gloucestershire (picture top).

A local Renaissance

There was another vital influence on the architecture of the Tudor period, especially in the grander houses: the art of the Renaissance and its revival of Classical art that had begun in Italy and spread northwards across mainland Europe. In architecture, this meant above all copying the orders – the “modes” of Classical architecture with their distinctive visual identities: Doric, Ionic, Corinthian, and so on.

But the Tudor builders did not go to Greece and copy temples; mostly they did not even get as far as Rome. They picked up their Classicism second- or third-hand – from books, from French buildings, from hints from the Netherlands – and added eccentric local twists of their own.

This gives English 16th century Classicism a unique and sometimes whacky character of its own. It’s full of curious carved curlicues and bizarre patterns. Its orders often don’t have the “correct” Classical proportions. It is sometimes combined with Gothic elements (Gothic, as a style for church-building, survived through the 16th century and into the 17th), as in the unusual church porch at Sunningwell (picture above). But it’s lively, and often fun to look at. One of the best places to find it is on grand houses and grand monuments in churches. Some of these monuments are large, canopied structures like little buildings in themselves. Others exhibit delightful carvings, hinting in their subject matter of the widening perspectives of English culture as the nation’s explorers sailed further and further around the world.

But it’s lively, and often fun to look at. One of the best places to find it is on grand houses and grand monuments in churches. Some of these monuments are large, canopied structures like little buildings in themselves. Others exhibit delightful carvings, hinting in their subject matter of the widening perspectives of English culture as the nation’s explorers sailed further and further around the world.

Big houses, prodigy houses

The big houses that contain this eccentric classical ornament include some of our most amazing buildings. Hardwick Hall, Derbyshire, with its vast windows and enchanting interiors, Burghley House with its skyline of pinnacles and turrets, and complex buildings like Kirby Hall are staggering structures, big, complex, and lavishly decorated. They combine classical details from the Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian orders with vast windows, and, usually, a symmetrical layout that is a far cry from the architectural jumble of medieval domestic building. Inside they have wooden panelling, elaborate fireplaces, and rich plaster ceilings adorning glorious rooms including spacious parlours and long galleries, These houses, vast, complex, and ornate, have rightly earned the nickname “prodigy houses”. They have their more modest cousins, too: manor houses that share some of the characteristics of Tudor architecture, but sometimes with more ornate gables and a sprinkling of classical details that seems to recall their more lavish counterparts.

Inside they have wooden panelling, elaborate fireplaces, and rich plaster ceilings adorning glorious rooms including spacious parlours and long galleries, These houses, vast, complex, and ornate, have rightly earned the nickname “prodigy houses”. They have their more modest cousins, too: manor houses that share some of the characteristics of Tudor architecture, but sometimes with more ornate gables and a sprinkling of classical details that seems to recall their more lavish counterparts.

Stuart architecture

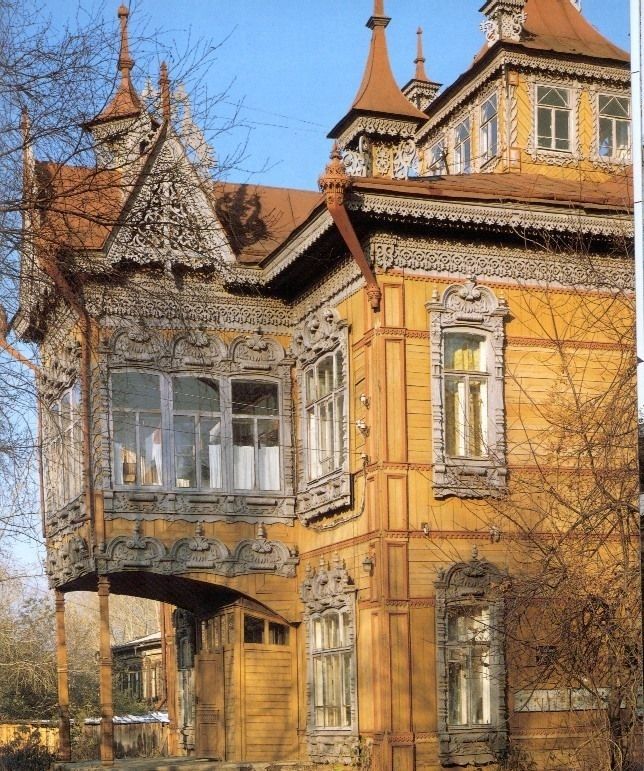

When James I came to the throne as the first Stuart king of England in 1603, the diverse traditions of Tudor architecture continued. Timber-framed construction was still often used for smaller buildings. In some high-status houses, timberwork could be highly elaborate and ornate, as in the house that is now the Feathers Hotel in Ludlow, Shropshire. Large country houses with symmetrical rows of large mullioned windows, bays, and ornate interiors were still built – Chastleton in Oxfordshire is one example; Rousham, in the same county, although altered, is another. Naas House in Gloucestershire, a third, enlivens this style of architecture with an delightful ogee-shaped cupola and a rooftop viewing platform. At Stanway, Gloucestershire, the outstanding gatehouse is in this style, but with various classical elements, such as the columns on either side of the entrance. Buildings like these could feature interiors that were panelled with wood and adorned with riotous carving very much derived from the Tudor mode, as in the extraordinary overmantel in the solar at Stokesay Castle. Town buildings could still display a rustic version of classicism and mythology in their decoration, or rows of plain, vaguely classical arches in their structure. The vernacular tradition continued when it came to smaller houses and buildings such as schools. And Gothic was still sometimes used for churches.

Naas House in Gloucestershire, a third, enlivens this style of architecture with an delightful ogee-shaped cupola and a rooftop viewing platform. At Stanway, Gloucestershire, the outstanding gatehouse is in this style, but with various classical elements, such as the columns on either side of the entrance. Buildings like these could feature interiors that were panelled with wood and adorned with riotous carving very much derived from the Tudor mode, as in the extraordinary overmantel in the solar at Stokesay Castle. Town buildings could still display a rustic version of classicism and mythology in their decoration, or rows of plain, vaguely classical arches in their structure. The vernacular tradition continued when it came to smaller houses and buildings such as schools. And Gothic was still sometimes used for churches.

But in London a new stylistic wind was blowing, bringing a more scholarly, correct form of classicism. The chief exponent of this new classicism was Inigo Jones, who designed buildings for the royal court. Jones visited Italy, studied the architecture there, and read Andrea Palladio’s great architectural textbook, I Quattro Libra dell’architettura. He became one of the most influential of all English architects.

Jones visited Italy, studied the architecture there, and read Andrea Palladio’s great architectural textbook, I Quattro Libra dell’architettura. He became one of the most influential of all English architects.

Jones’s buildings as a result are much more correctly classical than anything produced in England before. They have correct orders, and the proportions are perfect – rooms are often in the shape of perfect cubes or double cubes, for example. Only a handful of his buildings survive, but they have been very influential. The Banqueting House in Whitehall, the Queen’s House in Greenwich and St Paul’s church, Covent Garden, introduced the British to porticoes, properly designed orders, and Classical proportions, and helped set the style for decades, even centuries to come.

Other classicists followed, one of whom designed the tantalizing gateway near the church in Great Tew, Oxfordshire. One of these 17th-century classicists was Jones’s associate Nicholas Stone, designer of, amongst other things, the old water gate (picture above) now marooned in the Embankment Gardens in London. Stone developed the muscular classicism typified by this little building into something more curvaceous and authentically baroque in one building, the extraordinary porch of St Mary's church, Oxford; this baroque style was closely allied to the high-church beliefs of Archbishop Laud and his followers, and its development was cut short by the Civil War. The unique classical windmill at Chesterton, Warwickshire, is another example of the unusual ways in which the new architecture could be employed. Already, in early-17th century buildings like this, a more vigorous, eccentric kind of classicism was developing out of the chaste and pure style of Inigo Jones. It's possible to see the influence of this kind of vigorous, proto-baroque work in more modest timber-framed houses, with their fancy gables, rows of bow windows, and pargetted decoration – there is an example of this on a house of 1650 in Banbury.

Stone developed the muscular classicism typified by this little building into something more curvaceous and authentically baroque in one building, the extraordinary porch of St Mary's church, Oxford; this baroque style was closely allied to the high-church beliefs of Archbishop Laud and his followers, and its development was cut short by the Civil War. The unique classical windmill at Chesterton, Warwickshire, is another example of the unusual ways in which the new architecture could be employed. Already, in early-17th century buildings like this, a more vigorous, eccentric kind of classicism was developing out of the chaste and pure style of Inigo Jones. It's possible to see the influence of this kind of vigorous, proto-baroque work in more modest timber-framed houses, with their fancy gables, rows of bow windows, and pargetted decoration – there is an example of this on a house of 1650 in Banbury.

Later Stuart architecture

In the wake of Jones came a number of architects who developed his ideas and pursued ideas of their own. Some of them, John Webb for example, picked up the classical thread where Jones left it. Others evolved a type of house that became especially influential and is seen as quintessentially English. This kind of house had symmetrical facades with rows of identical windows, a central doorway, a hipped roof with dormer windows, and tall chimneys. A beautiful early example in brick is the Old House at Kibworth Harcourt, Leicestershire. Another, in stone and rather grander, is Nether Lypiatt Manor in Gloucestershire. Sill larger and more famous examples, such as the influential house of Coleshill (no longer standing), helped spread the fashion for this kind of house far and wide.

Some of them, John Webb for example, picked up the classical thread where Jones left it. Others evolved a type of house that became especially influential and is seen as quintessentially English. This kind of house had symmetrical facades with rows of identical windows, a central doorway, a hipped roof with dormer windows, and tall chimneys. A beautiful early example in brick is the Old House at Kibworth Harcourt, Leicestershire. Another, in stone and rather grander, is Nether Lypiatt Manor in Gloucestershire. Sill larger and more famous examples, such as the influential house of Coleshill (no longer standing), helped spread the fashion for this kind of house far and wide.

Both of these threads came together in the work of the most famous of all English architects, Christopher Wren. Wren, a scientist and mathematician as well as an architect, brought architectural ideas – ideas of space, form, and decoration – together in new ways. He is well known as the architect of St Paul’s Cathedral, with its ingeniously designed dome, but also created a host of small churches in the city of London. Many of these bring together Classical proportions with the Gothic idea of the spire to make structures unlike anything else before them. Wren could also design more purely Gothic structures, as his church of St Mary Aldermary shows. Not every church was influenced by Wren, however, as the extraordinary folk-art decoration at Bromfield, Shropshire, shows.

Many of these bring together Classical proportions with the Gothic idea of the spire to make structures unlike anything else before them. Wren could also design more purely Gothic structures, as his church of St Mary Aldermary shows. Not every church was influenced by Wren, however, as the extraordinary folk-art decoration at Bromfield, Shropshire, shows.

But Wren's influence on classical buildings was profound and enduring – he probably advised the mason Christopher Kempster on one of England’s most magnificent town halls, the one that dominates the centre of Abingdon (picture above) – and Wren was also known for large houses built of brick with stone dressings, an enduring English style seen at Hampton Court Palace and also at London's Marlborough House, finished in the early-18th century.

Wren’s greatest pupil and sometime collaborator was Nicholas Hawksmoor, who worked with the master on St Paul’s and went on to design outstanding buildings – both churches and country houses – on his own. Hawksmoor’s buildings are more determinedly bulky in character than Wren’s, more willfully original. He likes great ponderous masses of masonry, unusually shaped towers and spires, and windows taking the form of circles or semicircles. His buildings, such as the great London churches of Christ Church Spitalfields, St Anne Limehouse, and St George in the East, are big and brooding and rather weird.

Hawksmoor’s buildings are more determinedly bulky in character than Wren’s, more willfully original. He likes great ponderous masses of masonry, unusually shaped towers and spires, and windows taking the form of circles or semicircles. His buildings, such as the great London churches of Christ Church Spitalfields, St Anne Limehouse, and St George in the East, are big and brooding and rather weird.

Hawksmoor passed on the torch to the third great late-Stuart architect, Sir John Vanbrugh, who excelled at vast, ponderous country houses as Hawksmoor excelled at churches. Vanbrugh had no formal training as an architect and had been a soldier and playwright before embarking on his first building, the vast Castle Howard. He worked with Hawksmoor and must have relied much on him to begin with. And Vanbrugh must have learned quickly. Buildings such as Castle Howard, Blenheim Palace, and Seaton Delaval have a strong architectural character. Their elaborate facades and vast, awe-inspiring interiors are a world away from the severity of the buildings Inigo Jones was designing a century before. The castle Vanbrugh built for his own use, though smaller in scale, shared the monumental quality of his grand country houses.

The castle Vanbrugh built for his own use, though smaller in scale, shared the monumental quality of his grand country houses.

Although Vanbrugh is famous for country houses planned on a vast scale, his influence was felt on much smaller buildings. Sometimes one finds, in a town not far away from a major Vanbrugh house, a small house with his hallmark masses and round-headed windows. An example in Oxford stands as a reminder of the influence of the Vanbrugh mode.

Meanwhile, in the countryside, many building projects continued that showed little interest in the sophisticated ideas of these advanced architects. Meeting houses, fior example, continued to be built in the prevalent domestic vernacular, like the late-17th century stone meeting house, now a village hall, in South Newington. Churches, on the other hand, were sometimes still built in a modified version of the Gothic style, a phenomenon sometimes referred to as the Gothic survival. There was also a tendency among rural builders to adapt traditional domestic architecture, with its mullioned windows and occasional classical details, to church architecture. One structure built along these lines is the isolated country church at Monnington on Wye, Herefordshire.

One structure built along these lines is the isolated country church at Monnington on Wye, Herefordshire.

* * *

Now click here for the story of English architecture from c. 1700 to 1837.

Houses 16th-17th centuries | History. Abstract, report, message, summary, lecture, cheat sheet, abstract, GDZ, test

As in the Middle Ages, in the XVI-XVII centuries. the type of dwelling depended on the geographical and climatic features of the area, as well as on the occupation and well-being of its owners. In the north of Europe, peasants lived in wooden houses or dwellings made in the “half-timbered” technique - bulk plastered walls were erected on an oak frame. In the south, where forests had previously been destroyed, dwellings were built of stone. The roof in the south was flat, and in the north - peaked. Sometimes it was covered with reeds, but more often with straw, which was fed to cattle in famine years, and when replaced with a new one, it was used to fertilize the soil. Often only a partition separated the living quarters from the place where the cattle were kept. nine0003

Often only a partition separated the living quarters from the place where the cattle were kept. nine0003

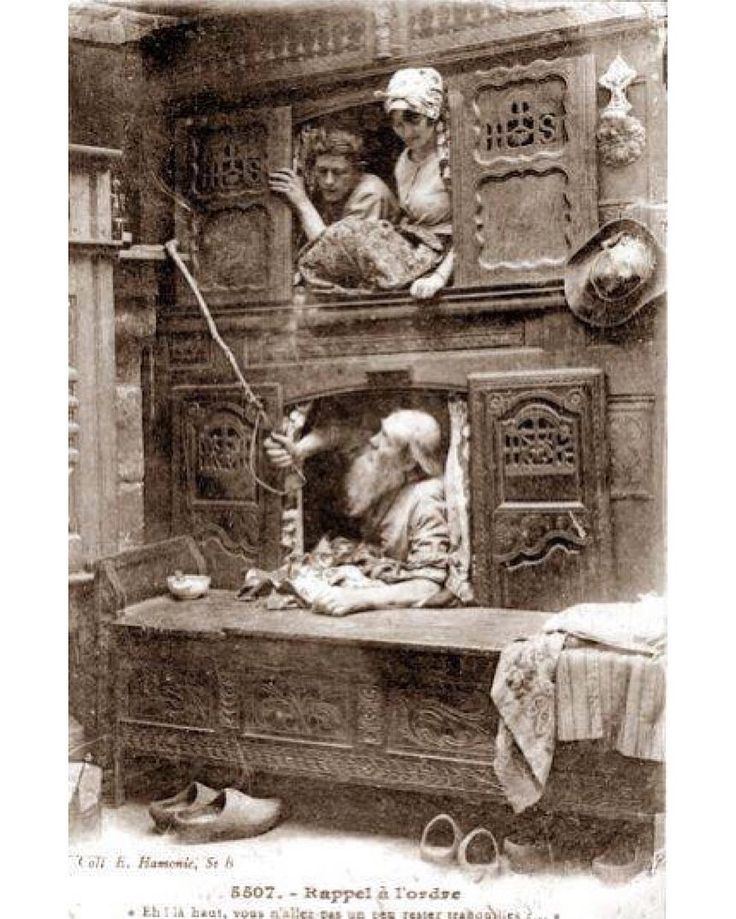

Usually the whole family lived in one large room, heated by a hearth for cooking. There was little furniture. Around the table stood benches, which were pushed back to the walls at night, covered with straw-stuffed mattresses or featherbeds, and turned into a bed.

Clothes and other household belongings were stored in a large chest. Kitchen utensils were also modest: a cast-iron cauldron, frying pans and pots, jugs and jugs, tubs and buckets. They ate and drank from wooden or clay bowls and goblets, and often there were not enough of them and they had to use common utensils. nine0003

Many low clay and wooden huts, covered with straw or shingles, remained in the cities. In them, as well as in the semi-basements or attics of multi-storey buildings, the urban poor lived. Some of the poor did not have a permanent roof over their heads at all. Frequent fires forced the townspeople to move on to the construction of stone dwellings. For the same purpose since the 17th century. roofs began to be covered with tiles, but it was expensive and not everyone could afford it. In the houses of merchants and artisans, a shop or workshop, as well as a kitchen, were located on the ground floor. On the second - the owner's family lived, there were a living room and bedrooms. The third floor was occupied by apprentices, apprentices and servants. The attic served as a warehouse. nine0003

For the same purpose since the 17th century. roofs began to be covered with tiles, but it was expensive and not everyone could afford it. In the houses of merchants and artisans, a shop or workshop, as well as a kitchen, were located on the ground floor. On the second - the owner's family lived, there were a living room and bedrooms. The third floor was occupied by apprentices, apprentices and servants. The attic served as a warehouse. nine0003

Silver chest. Flanders. 16th century Bedroom of Catherine de Medici Floors everywhere, even in poor houses, were covered with ceramic or stone tiles. Parquet was occasionally found in the palaces of the nobility; fashion for it began only in the XVIII century. In all strata of the population - from an ordinary peasant to a powerful monarch - the old custom has been preserved to cover the floor with straw in winter, and in summer with fragrant herbs and flowers. They were replaced by straw mats, as well as carpets, which were laid not only on the floor, but also on tables, chests and even on cabinets. nine0003 They were replaced by straw mats, as well as carpets, which were laid not only on the floor, but also on tables, chests and even on cabinets. nine0003 The plank floor of the upper floor served as the ceiling for the lower one. His until the XVIII century. not plastered, but covered with cloth or painted with patterns. Wealthy people also covered the walls with upholstery fabrics. Cheap paper wallpapers (they were called "dominoes") at first were in demand only among the poor population and only over time gained wide popularity. In the XVI century. learned how to make truly transparent glass. There were more windows with it both in cities and in villages, however, glass could not completely replace oiled paper and glassine. nine0003 When choosing furniture, we paid special attention to its comfort and appearance. The range of furniture has become wider, and the furniture itself has become more practical and more beautiful. The furniture was polished, decorated with carvings, artistic painting and gilding. Loading... nine0003 XVI century Letter about the house of the German banker Raimund Fugger. What a luxury in Raimund Fugger's house! Its vaults are supported by marble columns. It has spacious and beautiful rooms and halls, and the most beautiful of them is the study of the owner himself, with a gilded ceiling and an extremely luxuriously made bed. Adjacent to it is the chapel of St. Sebastian, with chairs made of valuable wood of very skillful work. But its main decoration is beautiful paintings. We were surprised by the collection of ancient monuments that we saw on the top floor of the house ... In one room there were coins and bronze statues, in the other - stone statues, some of them were colossal.

Seating furniture - chairs and armchairs - were made with high backs and curved armrests; they were covered in fabric or leather. Tables were made rectangular and oval, with legs of various shapes. The bed had a high headboard and a carved wooden canopy raised on posts: it was supposed to protect the sleepers from insects. Bed linen was used very rarely, the bed was covered with cloth and silk blankets. The rooms were decorated with mirrors in exquisite frames, candlesticks, clocks on stands, decorative vases, curtains and curtains. nine0003 Meanwhile, true comfort did not exist even in the homes of the nobility. A separate bathroom was considered a great luxury there, as, by the way, was a toilet with a water drain, invented in the 16th century.

XVI century The story of an Italian traveler about the home life of the inhabitants of the city of Zurich. In all the local houses, immediately after the morning prayer of the maid, and where there are none, then the housewives themselves begin to clean the rooms, sweep the corridors and the porch, wash and clean the benches and other utensils. Questions about this item:

ch. 16th-century residential buildings ?

The rear facade looks somewhat more interesting, which is reviving an elegant turret: But the most interesting is located in the yard: A couple of biblical "Golovypov" - David: and Yudifa: of the Harmin And the heads of those who hold this coat of arms: Gallery: It looks like it was a monkey: "We are blacksmiths and our spirit is young": There is another hotel nearby (appearing to be from the same era): still barmaglot): Only the aristocracy could afford stone hotels.  Most of the local residents made do with half-timbered houses. A couple of these beauties are also nearby: Most of the local residents made do with half-timbered houses. A couple of these beauties are also nearby: They are decorated with absolutely charming decor: On Saturday, September 15, excursion "Belly of St. Petersburg. Around Sennaya Square" will take place. |

Wardrobes of various types and purposes were widely used: in some they kept clothes, in others - dishes and cutlery, in others - books. Italian furniture makers enjoyed the fame of the most skilled craftsmen in Europe and trendsetters in furniture fashion.

Wardrobes of various types and purposes were widely used: in some they kept clothes, in others - dishes and cutlery, in others - books. Italian furniture makers enjoyed the fame of the most skilled craftsmen in Europe and trendsetters in furniture fashion.  We were told that all these sights were brought here at great cost from various countries, mainly from Greece and Sicily. The owner himself is an educated and noble man. nine0003

We were told that all these sights were brought here at great cost from various countries, mainly from Greece and Sicily. The owner himself is an educated and noble man. nine0003  the English. The level of hygiene, compared with the Middle Ages, decreased: fear of disease forced the city baths to be closed. A full body wash was treated like a medical procedure and was arranged at best once a year. Instead of washing, the face and hands were wiped in the morning with a wet towel. Heating and lighting remained a serious problem. The house heated the kitchen hearth, fireplaces and stoves. Only the rich could afford fireplaces; stoves were more affordable. In the south, braziers were used. Heating was expensive, so often only one bedroom was heated. Torches, candles, and a kitchen hearth served as a source of artificial lighting. Material from the site http://worldofschool.ru

the English. The level of hygiene, compared with the Middle Ages, decreased: fear of disease forced the city baths to be closed. A full body wash was treated like a medical procedure and was arranged at best once a year. Instead of washing, the face and hands were wiped in the morning with a wet towel. Heating and lighting remained a serious problem. The house heated the kitchen hearth, fireplaces and stoves. Only the rich could afford fireplaces; stoves were more affordable. In the south, braziers were used. Heating was expensive, so often only one bedroom was heated. Torches, candles, and a kitchen hearth served as a source of artificial lighting. Material from the site http://worldofschool.ru  The rooms are furnished very simply, often the whole decoration is clean and tidy. The most luxurious part of the chambers are the wooden panels that sheathe the walls. On each panel, either a portrait or a garland is carved in walnut. Such wall paneling protects from the winter cold, but the dark color of walnut and lacquer, which is covered with pine panels, makes the rooms gloomy. This is also facilitated by narrow and low windows and low floor heights. In winter, the rooms are heated by large stoves. There are few utensils, and she is not rich. Long benches were placed along the wall and around the large table. Guests in rich houses are given wooden chairs upholstered in velvet and trimmed with gold or silver fringe. Poor people use cloth or leather instead of velvet, and pillows embroidered by the women of the family are placed on top. The same embroidered carpets cover the holidays and tables. These cheerful and strong people give chairs only to the old and sick. Expensive dishes are used only on holidays.

The rooms are furnished very simply, often the whole decoration is clean and tidy. The most luxurious part of the chambers are the wooden panels that sheathe the walls. On each panel, either a portrait or a garland is carved in walnut. Such wall paneling protects from the winter cold, but the dark color of walnut and lacquer, which is covered with pine panels, makes the rooms gloomy. This is also facilitated by narrow and low windows and low floor heights. In winter, the rooms are heated by large stoves. There are few utensils, and she is not rich. Long benches were placed along the wall and around the large table. Guests in rich houses are given wooden chairs upholstered in velvet and trimmed with gold or silver fringe. Poor people use cloth or leather instead of velvet, and pillows embroidered by the women of the family are placed on top. The same embroidered carpets cover the holidays and tables. These cheerful and strong people give chairs only to the old and sick. Expensive dishes are used only on holidays. Everyday table utensils were made of earthenware and wood; for the rich, pewter. nine0003

Everyday table utensils were made of earthenware and wood; for the rich, pewter. nine0003