Pruning rhododendrons after flowering

Pruning Rhododendrons — Seattle's Favorite Garden Store Since 1924

Dan Gilchrist

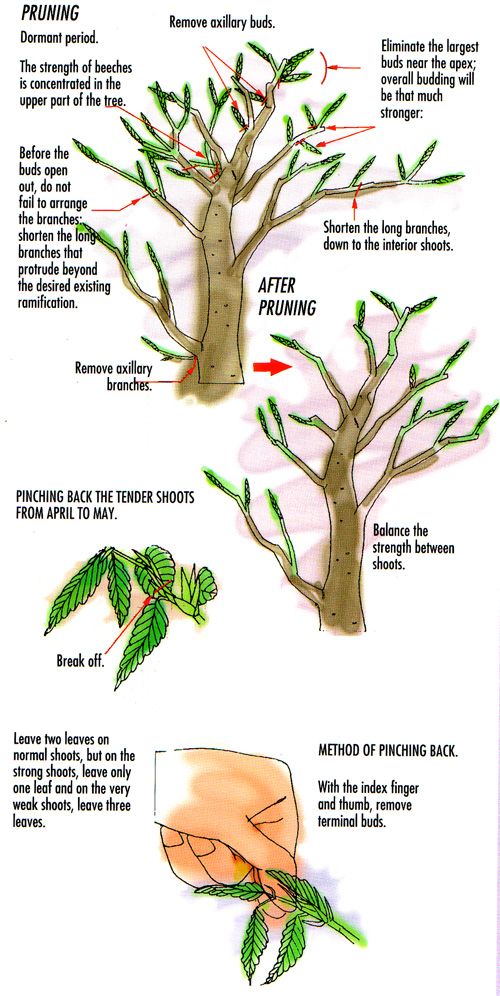

Pruning

Dan Gilchrist

Pruning

Rhododendrons, among the Maritime Northwest’s most beloved plants, can vary from two-foot-high dwarf shrubs to 30-foot trees. They are often multi-trunked, or single-trunked but branching into three or more main trunks close to the ground. Most varieties don’t typically need a lot of pruning for their first several years. Some stay compact and tidy; others develop an open habit and need little pruning other than occasional thinning and nipping back of a few wayward shoots.

Over time, many rhodies grow a dense weave of thick-wooded branches, and the thought of pruning one can intimidate all but the most experienced gardener. Of course, we are here to help! Many of the principles of pruning trees and shrubs that we have covered in other blog posts (like Pruning 101) also work for rhododendrons. But rhodies can pose a few unique challenges.

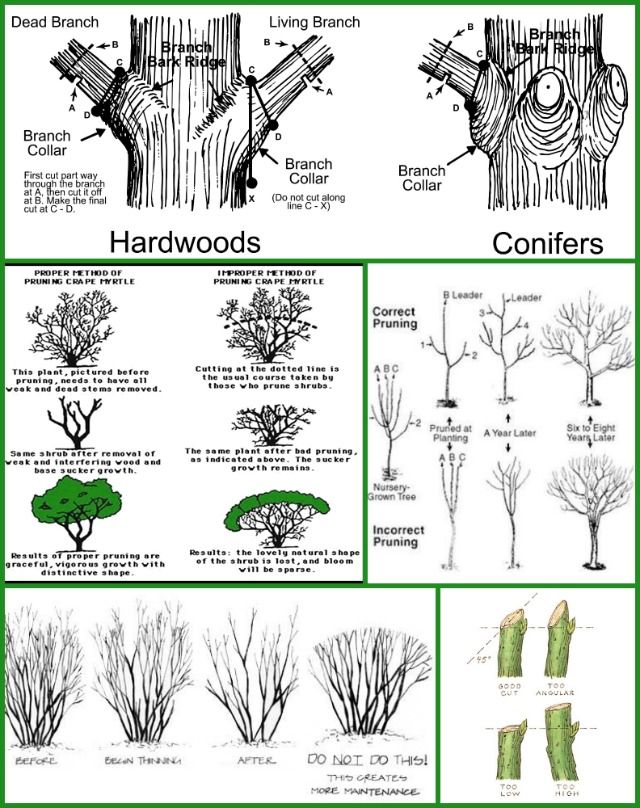

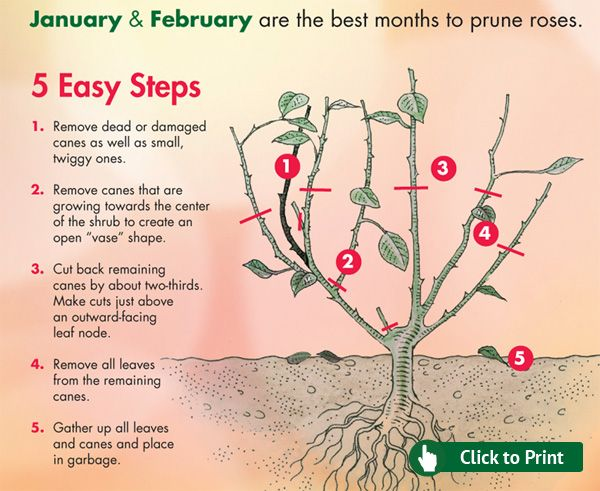

Let’s start with some basics. Most pruning projects are a combination of thinning and heading cuts. Thinning tends to disperse and often slow down growth. It reduces the density of a plant. It’s best to start pruning with a “clean out” from the inside of the plant, removing branches which are dead, broken, diseased and crossing or chafing each other.

Heading (including pinching and shearing) tends to concentrate and stimulate growth. It increases the density, such as in hedging. The majority of cuts during pruning should be thinning cuts unless you are maintaining a hedge or renovating a tree or shrub by severely cutting back.

For most pruning, leave a minimal stub when you cut off a branch. Don’t leave a long, ugly, dead end branch to die off and attract pests. But also don’t cut it so close as to damage the collar tissue on the mother branch, which it needs to grow over the wound.

Rhododendrons are somewhat unusual in that they will often resprout from cut, bare (living) branches. We describe this advantage under RESTORING below.

We describe this advantage under RESTORING below.

To identify whether a bare branch is still alive or dead, make a little scratch in the bark, revealing the thin cambium layer just below. If it's bright green, it's still alive and might still sprout this season. If it's brown, rotting or dry looking, it's dead.

Note that on larger rhododendrons with thicker branches, small hand pruners might be too small for most cuts. For these you may need loppers and pruning saws.

A thinning cut redirects growth to a specific branch.

A heading (shearing) cut forces dense growth on the shrub’s face.

Basic thinning of a shrub: removing random inner branches reduces density while preserving the plant’s shape and character.

WHY PRUNE?

As with pruning any plant, ask yourself these questions:

“Do I really need to prune this plant, and why?”

“What does this plant want to do?”

“What do I want this plant to do?”

Has it become an opaque blob in the center of your garden and you wish to make it a bit more open and treelike? Read about THINNING below.

Is it planted in too small of a space and you want to reduce its size or just head it back a little? …REDUCING may be the answer.

Is it a leggy, sparsely blooming shrub that you would like to develop more leaves and flowers like it used to? …let’s talk about RESTORING.

Note: Just because you’ve always heard that you’re supposed to prune your rhododendron doesn’t mean you’re obligated to do so. Plant maintenance should not be a prescribed, automatic chore, but rather a flexible solution to a specific problem.

TIMING

You can prune a rhododendron almost any time of year without harming it, but the best time is within a few weeks after it has finished blooming, to give it the maximum time to set flower buds for next year. Waiting too late is no disaster, but could mean fewer blooms for the next year (or a few years if you are pruning it back hard). If you’re doing a major restoration with severe cutting back, the best time is late winter/early spring, before the growing season. Beyond that, avoid extremes of hot (over 85ºF) or cold (under 25ºF) for pruning most plants in our area.

Beyond that, avoid extremes of hot (over 85ºF) or cold (under 25ºF) for pruning most plants in our area.

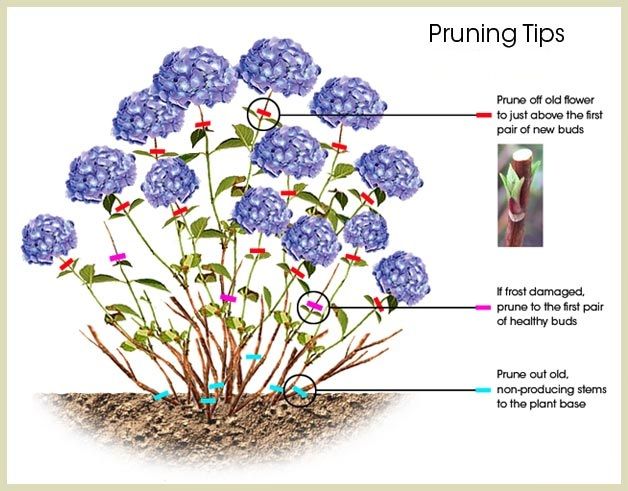

DEADHEADING

Independent of pruning you might want to deadhead (snap or cut off spent bloom stalks). We do that to many flowering plants in order to interrupt the energy normally going into seed production and redirect it toward new bloom buds. Also, it visually cleans them up.

Routine deadheading is fine for younger rhodies, but on a large, mature one, it might not make a significant difference for future blooming. Plus, it can take a lot of time! If lower maintenance is a priority, it’s not always necessary to deadhead.

After blooming: deadheading and optional thinning of new sprouts.

Option to thinning new sprouts: cutting bare branches to activate latent buds.

We mentioned the emphasis on thinning to reduce density and reveal a shrub’s natural form, rather than a lot of heading (or shearing). But thick branches, dense foliage and the interweaving tendency of some rhododendrons call for a bit more patience.

But thick branches, dense foliage and the interweaving tendency of some rhododendrons call for a bit more patience.

Before and after thinning (and slight heading back) of a large rhododendron.

Before and after thinning (and slight heading back) of a smaller, upright rhododendron or azalea.

After the initial cleaning described in BASICS, you can start thinning, as we say, “inside-out, bottom-to-top, small-to-large.” Work from the inside of the shrub, usually at the bottom, randomly pruning off small branches at their base (where they sprout from a larger branch) and work your way up and out. You can also remove some of the lower branches to help the shrub “float” off the ground a bit more. Then start removing redundant branches which grow through the middle of other dense growth, unless they are major structural branches.

After pruning out several of these, step back to see what difference it is making in the density. You might notice larger branches which could also be removed unless it might create large holes in the shrub’s foliage mass. If there are several major branches crowded together, it’s good to thin out the mass.

You might notice larger branches which could also be removed unless it might create large holes in the shrub’s foliage mass. If there are several major branches crowded together, it’s good to thin out the mass.

Dealing with a tangled, weaving branching habit entails cutting one branch at a time and pulling it out of the tangle. As you reduce the density, you might also discover long, flexible branches you don’t wish to cut. You can sometimes “reweave” those out from other branches, helping to open up the shrub’s form.

Before and after thinning of a dense (and somewhat leggy) rhododendron.

Can you start to see through the shrub much more than when you started? If not, keep going. When you have one zone of the shrub that looks sufficiently thinned out, then move on to another zone achieve approximately the same density. You don't want to remove every last tiny branch inside the shrub. Thinning aims to improve the transparency of the plant, not skeletonize it.

After thinning the interior, you might still have an outer “shell” of crowded shoots which emerge from near the tips after blooming. You can thin out the numbers of those new shoots (sometimes they snap right off) or, if things are really crowded, cut some of their parent branches further back.

When you feel the whole shrub feels more open (we like to say that it can “breathe”), and not such a dense blob, you can stop! Always better to prune too lightly in one season, than too severely. We advise to not remove more than 25% of the living tissue in any one year.

Although heading back outer branches to shorten a plant is easy to understand and seems like a natural way to control the size, it can create a lot of future issues. Some plants tolerate frequent heading just fine, such as common hedging shrubs. But most plants are genetically “programmed” to reach a certain size range at maturity and will expend a lot of growth energy to attain that size.

If you just need to nip back a few long stragglers to clean up your plant, no problem. But if you try to reduce its natural size by more than about 20%, it can react, sending pent-up growth energy into aggressive sprouting. We further describe the risks below.

But if you try to reduce its natural size by more than about 20%, it can react, sending pent-up growth energy into aggressive sprouting. We further describe the risks below.

Shortening a rhody that wants to be much taller often results in a mess of new sprouts!

Rhodies react to heading cuts this way. That can be an advantage when trying to stimulate more leaf growth on a leggy plant, as explained below. But it complicates things if you wish to keep it unnaturally small.

Some rhododendrons can grow into trees 10 feet and higher. If you allow and even train them to reach their potential height through thinning, they can become dramatic, neighborhood landmark trees. There are many wonderful examples in our region, notably at the Rhododendron Species Botanical Garden in Federal Way, and UW’s Washington Park Arboretum.

But an all-too-common situation is a house with a front picture window about five feet above the ground. Years ago, someone (not you, of course!) planted a rhododendron or a group of them under the window for a pretty foundation planting. Either the the information provided by the plant seller suggested the shrub would not grow taller than 6 feet, or that it could grow larger, but that was “after 10 years” or the fine print was ignored altogether. In any case, the rhody is now big and crowding out the window, if not the whole house.

Years ago, someone (not you, of course!) planted a rhododendron or a group of them under the window for a pretty foundation planting. Either the the information provided by the plant seller suggested the shrub would not grow taller than 6 feet, or that it could grow larger, but that was “after 10 years” or the fine print was ignored altogether. In any case, the rhody is now big and crowding out the window, if not the whole house.

Right plant/wrong place… Reduce size? Remove? Or thin out to become landmark trees?

(photos: L-The Redeemed Gardener, R-The Outlaw Gardener)

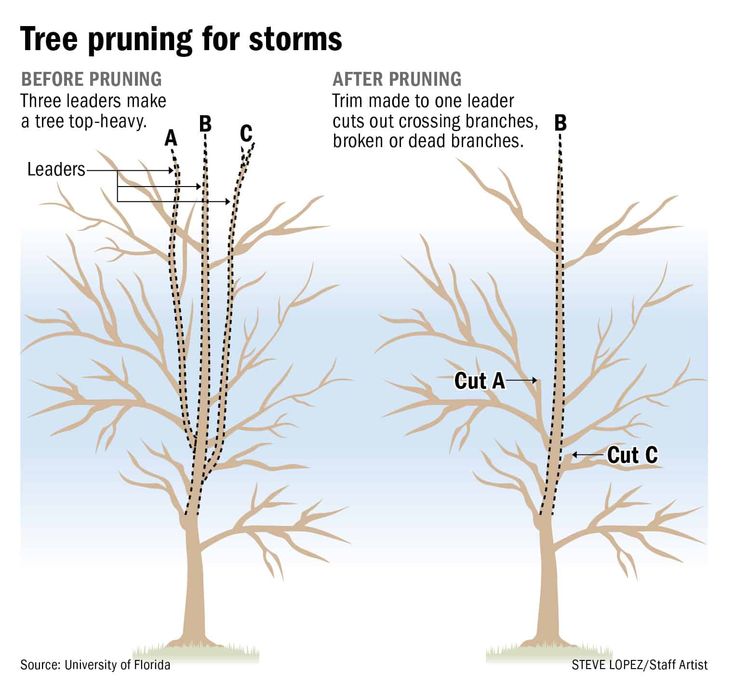

Unless you’re willing to significantly thin or remove this giant, the challenge is how to reduce it in a way that doesn’t make the tree look chopped or beheaded. It would be easy to just head it way back, as in REJUVENATING below. But after the initial clearcut, this would likely trigger aggressive sprouting, which can turn it into an even faster-growing, unattractive beast for years to come.

Think instead about redirecting growth energy from the upper leader(s) to lower secondary branches. The method for this is called releadering or drop crotching. Cut a leader branch (tallest one in a branch group) back to a lower side branch (at least half the thickness of the branch you are cutting). Now the lower branch is likely to become the new leader. On a typical rhody there are multiple leaders, so you would releader several of them to shorter branches.

Releadering to gradually reduce height: remove entire branches (rather than randomly heading them back) to transfer the leader growth to lower branches.

On a dense-foliage rhody (or any dense plant), if you shorten all the tallest leaders you will likely open up bare spots — open areas with bare branches and little foliage that were previously shaded out by what you have just removed. In time, these will resprout and fill in but it can take a year or several, depending on the type and vigor of the plant.

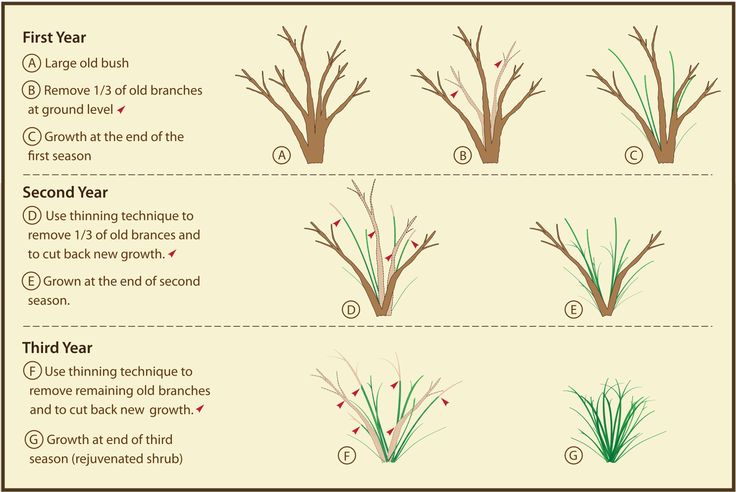

With any major reducing, restoring or rejuvenating, we recommend to avoid (if possible) doing this all at once. If you can spread the job over two or three years you might minimize the bare or chopped look and the overreactive regrowth.

For example, you could do releadering on maybe 1/3 or 1/2 the number of tallest leaders, so the top layer is thinned out but not totally removed. Then after a year or two with the lower layers growing in, you can cut back the rest of the top layer. But remember: it may still react to a major reduction over time. Unnatural pruning creates a high-maintenance plant.

Older rhodies can develop quite a leggy habit, especially after years of being crowded by neighboring plants, struggling under dense trees, or just having aged a long time without any pruning attention. Others may suffer low vigor from poor drainage, depleted soil, or other stresses.

Restorative pruning can make quite a difference, along with improving the watering, mulching, and fertilizing of a struggling plant. If the shrub is heavily shaded (unless it’s possible to thin out overhead trees), blooming might always be sparse. And although these methods can help revive most shrubs, some might have deeper health issues and not sprout as well.

If the shrub is heavily shaded (unless it’s possible to thin out overhead trees), blooming might always be sparse. And although these methods can help revive most shrubs, some might have deeper health issues and not sprout as well.

A leggy habit is long, tangled, bare branches with few leaves or flowers out on the tips. Restoring a more balanced branching pattern and redirecting growth energy back into foliage and blooming often takes a combination of thinning, untangling/reweaving, and heading back some bare branches.

Restoring a leggy rhododendron with thinning and some heading, to encourage more interior growth.

For long bare branches in the interior that are alive (look for leaves at their ends or use the scratch test described under BASICS), remove any that are causing crowding, and perhaps choose a few to head back, to stimulate their latent buds. Live rhododendron trunks and branches are lined with latent buds (conspicuous or hidden) which often “wake up” when the growth above them is removed.

Combination of thinning and heading back bare branches to induce sprouting and reduce legginess.

If you don’t want to cut off a branch you can try “nicking” the bark just above a latent bud (if the bud is conspicuous). Make a small cut with a pruner blade or small saw barely deeper than the cambium layer. This can “fool” the bud into sensing that the whole branch has been cut, activating new growth.

…OR REJUVENATING ONE

If you feel you must rejuvenate (or renovate) one from scratch, cutting it down to a few primary branches a few feet high will, if it is healthy, cause it to sprout and grow quickly. Late winter/early spring is the season for this. Then you can thin and manage the new branches as they develop using the methods we have described here.

Renovating an old rhododendron from the ground up. (C and R photos: ProperLandscaping. com)

com)

Some gardeners might choose this if it’s an unusual, hard-to-find variety or of sentimental value. Again, consider doing this gradually over two or three years rather than one fell swoop. But if it’s not an exceptional plant, weigh this option with the amount of work (and awkward habit) ahead, vs. just replacing it with a new rhododendron.

There are other shrubs that can be pruned in a similar way to rhododendrons. Common examples include Lily-of-the-Valley shrub (Pieris), mountain laurel (Kalmia), Camellia, strawberry tree (Arbutus unedo), and English and Portuguese laurels (Prunus laurocerasus and lusitanica). These, as well as some popular deciduous shrubs such as lilac, mockorange and forsythia, have latent buds which can sprout from bare branches, so most can tolerate occasional hard pruning.

So the pruning methods we have described apply similarly. On dense or overgrown plants, thin out the inner branching structure, manage multiple sprouts, and reduce or restore plants only if necessary.

Once again, don’t prune your rhododendrons just because “you’re supposed to” but in order to address specific problems and let them be healthy and beautiful.

Still have questions? We are always here to answer your care questions on this or any other gardening needs by emailing [email protected], via social media, or in person at the store!

Tagged: rhododendrons, rhododendron care, pruning techniques, shrubs, trees, pruning shrubs, pruning trees, advanced pruning

How And When To Prune Rhododendrons

How And When To Prune Rhododendrons

Robert L. Furniss

Portland, OR

"How do I prune my rhododendrons?" The usual answer to this frequently asked question

is, "Very little. Remove the dead and sickly branches and let the plants grow naturally." Sometimes

this is good advice. It applies best to small, bushy-type rhododendrons and to rhododendrons in woodland

and mass plantings, but it is not the whole story. At times it is adequate, even misleading.

At times it is adequate, even misleading.

Definition. Pruning is the removal of parts of a plant to control growth. More art than science, it is an adaptation of natural processes to achieve horticultural objectives. Broadly, pruning includes the removal of any unwanted parts of a plant, including flowers, buds, soft wood, hard wood, basal sprouts, and sometimes roots. Pruning is not a routine treatment applied cookbook style. Nor is it a substitute for requirements for vigorous growth, such as fertilizing, watering, controlling pests, and planting properly.

Objectives. Pruning is for some cultural purpose. Before plant surgery,

the grower should decide what the pruning is intended to accomplish. Is the grower trying to revitalize

treasured old plants, to produce plants for sale, to stimulate maximum number of highest quality flowers, to

enhance the year-around appearance of the plants, or to achieve some special landscape effect? Has

something gone awry that needs correcting? The kind and amount of pruning depends upon the nature of the

planting and the purpose of the grower.

Pruning can accomplish a lot. It can start early in the life of a plant, as in the heading back of nursery stock to achieve compactness. As the years roll by after planting, many fine rhododendrons decline, become leggy, or develop into brush heaps for lack of attention. Such plants often can be revitalized and improved by judicious pruning and training. Of course there are limits. Medium-sized 'Elizabeth' cannot be forced to grow tall by pruning, and giant-sized 'Loderi King George' cannot be dwarfed. Most rhododendrons respond well to pruning. Some that do not sprout readily from old wood cannot be much improved. Others that sprout abundantly should not be opened excessively to light. If in doubt, proceed cautiously, or seek expert advice.

When to prune. Pruning of hardened wood can be done at any time except

during periods of freezing weather. Early spring generally is best because the new growth

then has a full season in which to develop and mature. Pruning immediately after the blooming

period is standard practice. However, some rhododendrons that bloom very heavily should be

pruned prior to bloom to reduce the number of flowers and thus maintain vigor of the plant.

Thinning the flowers also can improve the quality and placement of the ones that remain.

Pruning immediately after the blooming

period is standard practice. However, some rhododendrons that bloom very heavily should be

pruned prior to bloom to reduce the number of flowers and thus maintain vigor of the plant.

Thinning the flowers also can improve the quality and placement of the ones that remain.

Summer pruning often results in lush sprouts that are subject to aphid injury

and may not harden sufficiently to withstand low winter temperatures. Deadheading, which is

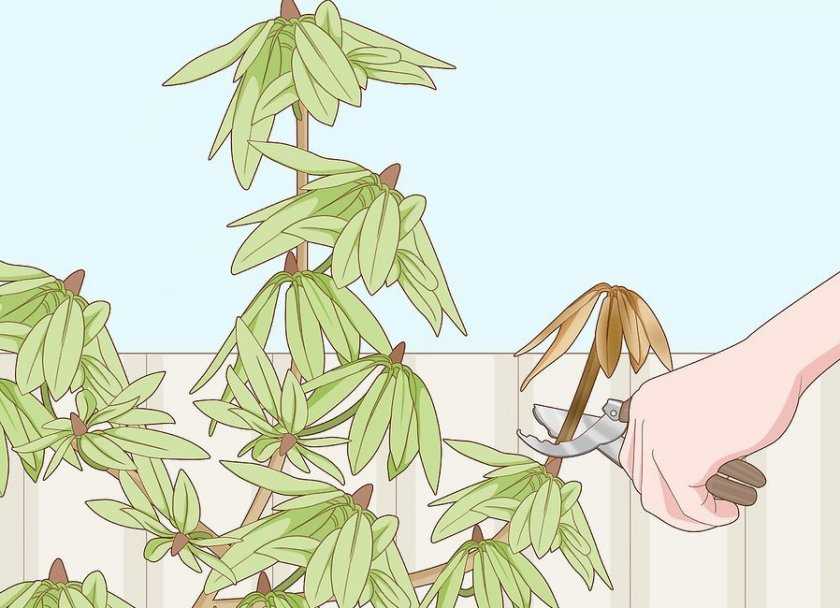

the removal of spent flowers, should be done soon after the flowers fade, taking care not to

injure the new growth. This important job helps control insects and greatly improves the

abundance and quality of the next year's bloom. Soft wood pruning, or pinching back, is

done during the growing season. Removal of terminal leaf buds and shoots to promote

branching should be done early in the season or from late summer on through fall and winter.

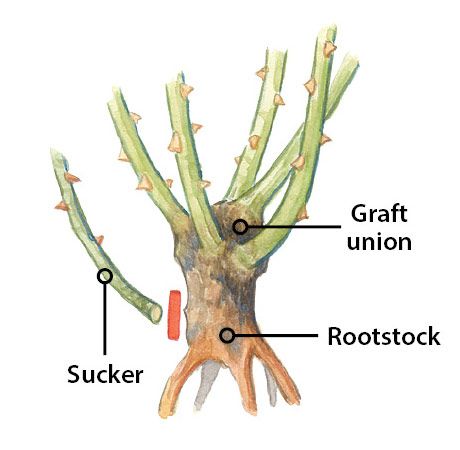

How to start. A good way to start to prune a rhododendron is

to crawl under it, look up, and decide what structural changes are needed. If the plant

has been long-neglected, it likely will be necessary first to cut out a tangle of dead branches.

Then remove cross branches and weak wood. Remove excess branches to give remaining ones

room to grow. Except when layering a plant, remove drooping branches that scrape the

ground and provide handy stepladders for weevils to climb and feed upon the leaves. Remove

spindly shoots that sometimes develop along the bole. Remove sprouts from under-stock on

grafted plants. These sprouts spring up from the base of a plant and produce flowers of

a different color, often lavender. Fortunately modern hybrids are mostly grown on their

own roots, and so remain true to color. In removing hardened wood, make clean cuts, prune

flush with the bole or main branches; do not leave stubs. Thinning the small outer branches

is the final step in the pruning process.

Thinning the small outer branches

is the final step in the pruning process.

Pruning for compactness. The compact, profusely budded rhododendrons

of the nursery trade usually are the objective of commercial growers and landscapers. These

plants are produced by good cultural methods, including de-budding and summer pruning of current

growth to induce multiple branching and abundant flowers. In the home garden, the day

ultimately comes when the branches become too numerous and need to be thinned to restore

high quality foliage and bloom. When this occurs, insect damaged, sun-scorched,

winter-injured, and scraggly foliage and branches should be among the first to be removed.

Before planting a rhododendron, keep in mind that it is best to select one that will not

outgrow the allotted space. A tall-growing variety just isn't suitable in front of a

picture window. No amount of pruning will make it fit there comfortably and

attractively.

Pruning to a single trunk. In some kinds of landscaping,

plants are pruned high and trained to a single trunk or a few main stems. This treatment

reveals the structure of the plant and texture of the bark, thus improving the year-around

interest and beauty of a planting. An arched canopy over a woodland-type pathway can be

achieved by high pruning of adjoining plants. The openness of a high-pruned plant

facilitates the placement of ladders for deadheading and grooming the top, and provides

ready access for watering, fertilizing, and mulching. If a single-trunk plant is the

objective from the beginning, heading back can be delayed to encourage height growth. Also,

while a plant is young and flexible, its trunk can be shaped for character by bending. If

a plant has branched very low or has multiple stems, it will be necessary to cut away some

lower branches and all except one or a few of the stems to achieve the desired tree-like effect. The 'Loderi' and 'Naomi' hybrids and many other large varieties respond well to the single trunk

treatment. Bushy varieties do not; for example, 'CIS,' 'Bric-a- brac,' R. racemosum,

R. williamsianum, and others.

The 'Loderi' and 'Naomi' hybrids and many other large varieties respond well to the single trunk

treatment. Bushy varieties do not; for example, 'CIS,' 'Bric-a- brac,' R. racemosum,

R. williamsianum, and others.

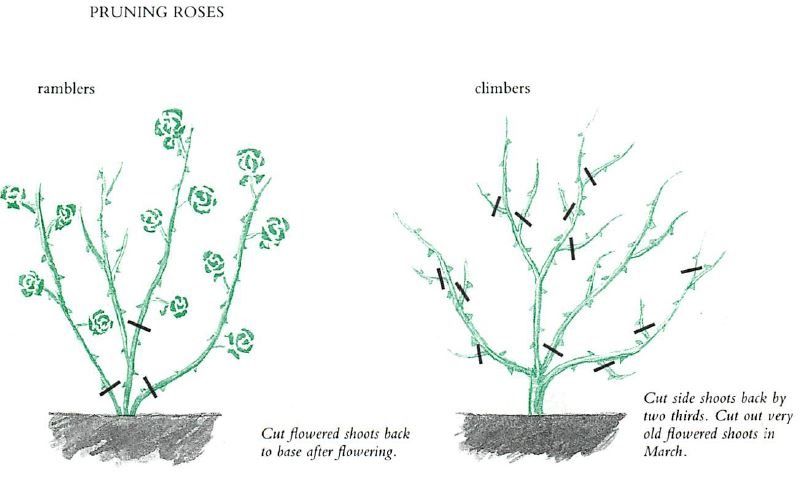

Pruning for special effects. Sometimes it is desirable to

prune a group of rhododendrons so that the foliage on one side is allowed to cascade nearly

to the ground and that on the other side is pruned high to reveal the beauty of the trunk

and large branches. Rhododendrons pruned in this way exhibit an unbroken bank of

foliage or bloom when viewed from one side and a wooded-dell effect from the other. The

exposed trunks should face the north or east, or be protected from the sun by buildings or

other plants.

In general the profile of rhododendron plants is regular. Individually

they are difficult subjects to train for asymmetrical or tiered effects. These landscape

effects can best be achieved by grouping rhododendrons of different sizes and textures, or

by inter planting them with suitable companion plants. However, some azaleas, such as

R. calendulaceum, are exceptions to the rule in that they respond beautifully to

pruning for irregular effects.

However, some azaleas, such as

R. calendulaceum, are exceptions to the rule in that they respond beautifully to

pruning for irregular effects.

Pruning to rejuvenate. Rhododendrons that have outgrown

their site or have become tall, ungainly, and sparse of bloom can be rejuvenated by

judicious pruning, preferably in early spring. Don't attempt to do it all at once.

The plant likely will survive one-shot surgery, even make a strong recovery, but it is no way

to treat an old friend. It is better to spread the rehabilitation over 2 or 3 years.

Each year cut back some of the heavy branches to latent buds. Let the light in to

encourage new shoots to form. Plants that have deteriorated in the top should be cut back

and rejuvenated with new growth originating low on the bole. Prune with the dual objective

of retaining the mature structure of the rhododendron and of improving its vigor and capacity

to bloom.

Pruning to salvage. When catastrophe strikes and a large plant is broken or otherwise severly injured, don't despair. It may be salvaged. In the wild our native rhododendron, R. macrophyllum, often is killed back to the ground by fire, only to sprout again from the root crown and in a few years regain full vigor. Cultivated rhododendrons that have to be cut back to a stump likewise frequently recover.

Pruning to facilitate moving. Sometimes large, long-established

rhododendrons have to be moved. This is a sizeable but relatively simple job. For best

results, it should be done in the fall or in early spring before new growth begins. The roots

are cut back (pruned) with a sharp shovel, leaving a wide but shallow pad of roots and soil. Hauled

or skidded to its new location, the plant should be set high in loose, well mulched soil. To ease

the shock of moving, some foliage should be pruned to compensate for the loss of roots. In part

this is accomplished by cutting off lower branches that hamper the moving and in part by pruning

unneeded upper branches. It is a good opportunity to shape a neglected plant.

In part

this is accomplished by cutting off lower branches that hamper the moving and in part by pruning

unneeded upper branches. It is a good opportunity to shape a neglected plant.

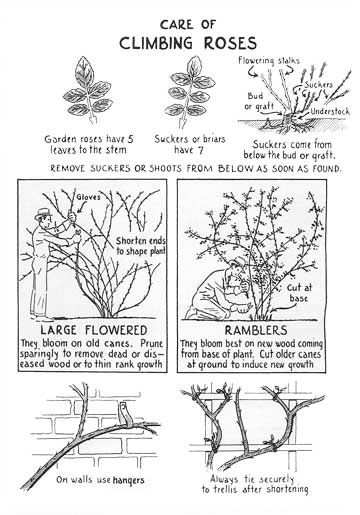

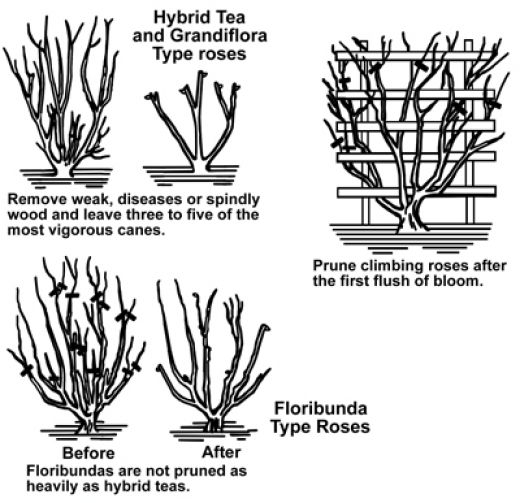

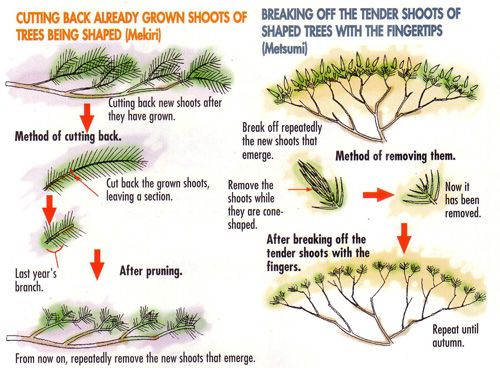

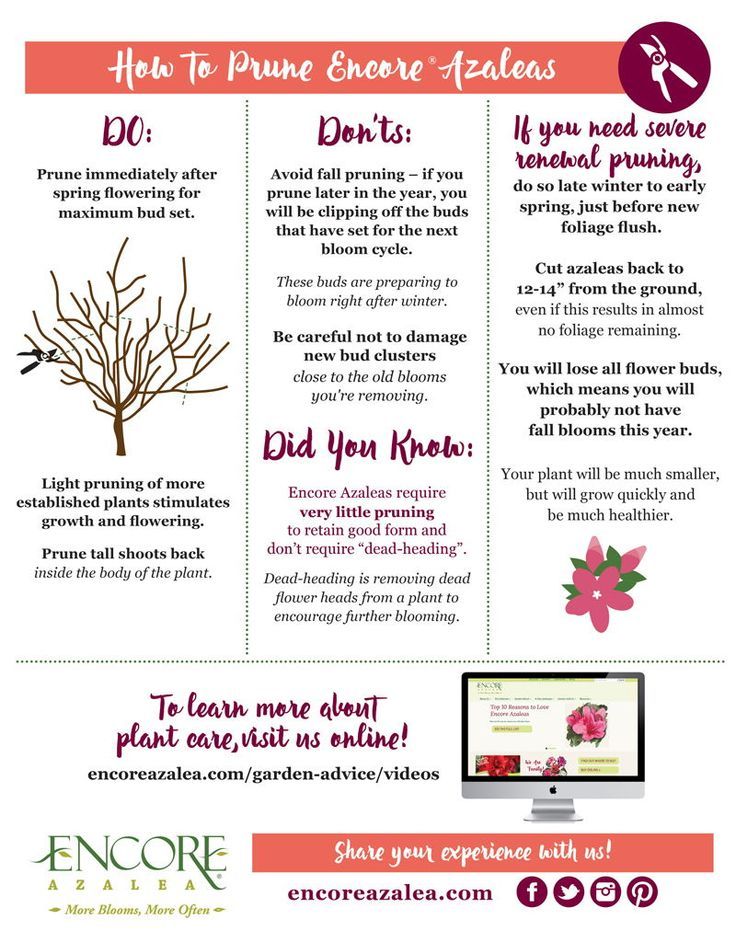

Pruning azaleas. Most of this article concerns broadleaved, evergreen rhododendrons. Azaleas require relatively less pruning, but some deciduous ones thrive better if the old shoots are periodically cut back to the ground to give new shoots growing room. Some azaleas that sprout vigorously or send up suckers from the spreading roots need to be thinned occasionally at the ground to prevent excessive bushiness. Azaleas can be made more compact by heading back the new growth a few inches in early summer. Some evergreen azaleas will stand shearing, a practice that is common in Japanese landscaping and which produces very dense mounds of foliage.

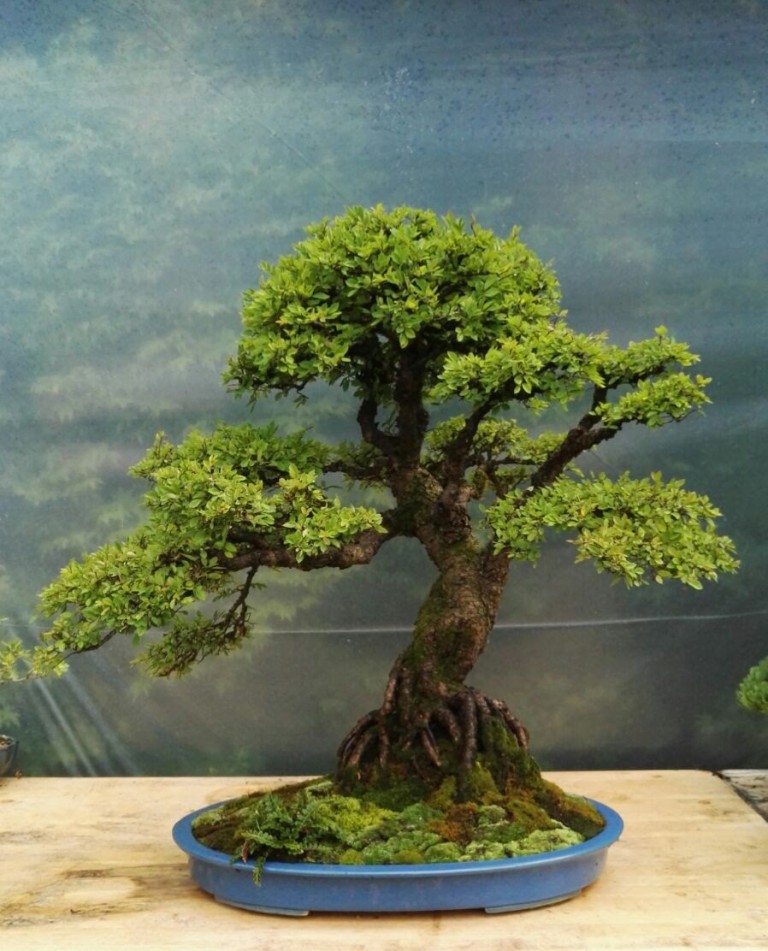

Pruning for bonsai. The ultimate in controlling growth by

pruning is the culture of bonsai. Some small-leaved rhododendrons and evergreen azaleas

are good material for bonsai. This specialized aspect of pruning and growing rhododendrons

is discussed in "Rhododendron Information," a book published by the American Rhododendron Society,

and in standard texts on bonsai.

Some small-leaved rhododendrons and evergreen azaleas

are good material for bonsai. This specialized aspect of pruning and growing rhododendrons

is discussed in "Rhododendron Information," a book published by the American Rhododendron Society,

and in standard texts on bonsai.

Treatment of pruned surfaces. It is often recommended that the cut surfaces resulting from pruning limbs an inch or more in diameter be treated with pruning compound. Probably more aesthetic than prophylactic in effect, this treatment appears to be optional with the grower.

Basic tools and references. Basic tools and procedures are discussed in standard references such as "The Pruning Manual" by L. H. Bailey and Sunset Magazine's "Pruning Handbook." Detailed procedures for pruning rhododendrons are discussed and illustrated in "Rhododendrons of the World" by David Leach.

A final word. In summary, it is a myth that rhododendrons

should not be pruned. The essential thing in pruning is to decide upon the purpose.

Then don't be afraid to apply the saw and pruners to achieve the desired result. The

rhododendrons will appreciate the attention and respond to it.

The essential thing in pruning is to decide upon the purpose.

Then don't be afraid to apply the saw and pruners to achieve the desired result. The

rhododendrons will appreciate the attention and respond to it.

90,000 care for rhododendrons after flowering

Photos of the author

in the article:

1. Media care measures

2. Prevention and treatment of diseases

3. Formation

4. Feeding

The success of the enterprise depends on the degree of training to him. Therefore, in order to ensure guaranteed flowering of rhododendrons next year, it is necessary now, after the rhododendrons have faded, to carry out a number of necessary agrotechnical measures. This is especially true for those rhododendrons that did not bloom this year for various reasons. nine0005

What should I do first?

Cleanliness and health should always come first. Faded inflorescences should, if possible, be carefully removed by breaking or cutting off (peduncles are very dense and thick) at the base. Be careful not to damage new shoots.

Be careful not to damage new shoots.

Clean the leaves of evergreen rhododendrons from adhering petals so as not to provoke various spots.

Look inside the bushes. There will certainly be dried branches that should be removed immediately. You should also clean the near-trunk circle from old leaves - such a mulch for rhododendrons is useless.

At the same time, check the degree of penetration of the root collar. It should be about level with the surface. If it has gone much deeper, you will have to wait for cool weather and plant the rhododendron higher.

The leaves of rhododendrons not only delight with their beauty, but also immediately indicate problems with the bush. We saw that the leaves between the veins began to turn yellow - it's time to take measures against chlorosis. Chlorosis, not being a disease as such, can greatly undermine the health of rhododendrons. What to do in this case? nine0005

First, check if the soil under the rhododendron has become very compacted. The hand should easily go deep into the ground. If clay or heavy loam “won”, we prepare a new, wider planting hole and transplant the rhododendron. Or, stepping back from the base of the bush half a meter, we dig a wide trench and fill it with a mixture of high-moor peat (3 parts), sand (1 part) and light fertile soil (1 part) plus 5 liters of biohumus and a glass of bone meal. All of the above applies to young bushes. To improve the air and moisture permeability of the soil under the already long-growing rhododendrons, carry out elementary sanding. Take a pitchfork and, according to the projection of the crown, slightly deepening towards the center, make punctures every 10 cm, cover the surface with sand with a layer of 2-3 cm and pour it well a couple of times. nine0005

The hand should easily go deep into the ground. If clay or heavy loam “won”, we prepare a new, wider planting hole and transplant the rhododendron. Or, stepping back from the base of the bush half a meter, we dig a wide trench and fill it with a mixture of high-moor peat (3 parts), sand (1 part) and light fertile soil (1 part) plus 5 liters of biohumus and a glass of bone meal. All of the above applies to young bushes. To improve the air and moisture permeability of the soil under the already long-growing rhododendrons, carry out elementary sanding. Take a pitchfork and, according to the projection of the crown, slightly deepening towards the center, make punctures every 10 cm, cover the surface with sand with a layer of 2-3 cm and pour it well a couple of times. nine0005

Secondly, mulch the surface of the ground under the rhododendrons with acidic high-moor peat (pH 3-4), a layer of at least 8-10 cm. Often used coniferous litter does not give the desired effect.

Thirdly, foliar fertilizing with iron chelate (Ferovit) 2-3 times with an interval of 10 days, add Zircon to the solution (according to the instructions). Such prevention is useful for all rhododendrons, including deciduous ones. The leaves will be healthier and more beautiful.

Such prevention is useful for all rhododendrons, including deciduous ones. The leaves will be healthier and more beautiful.

Fourth, try to water only with soft water, preferably rain or from the nearest reservoir. nine0005

Fifth, in severe cases, apply colloidal sulfur to the tree trunk - 40 g per medium-sized bush.

Prevention and treatment of various spots and fungal diseases

Yes, unfortunately, “aristocrats” also get sick, but if they are not started, the situation can be shifted in a positive direction. Diseased leaves should be removed and burned. Their beauty cannot be returned. But the emerging sprouts should maintain health. Indeed, during this period, a new phase of decorativeness of rhododendrons begins, when the entire bush is covered with young leaves, and for each variety and species they are special. Then we carry out therapeutic and prophylactic spraying with Horus (for young shoots), Rakurs, Raek or Ordan. Add pesticides to the solution. After all, scythes, aphids and other "evil spirits" will destroy tender sprouts - you won't have time to look back! Repeat the treatment every 2 weeks. nine0005

After all, scythes, aphids and other "evil spirits" will destroy tender sprouts - you won't have time to look back! Repeat the treatment every 2 weeks. nine0005

Another number of unpleasant and intractable diseases are verticillium and tracheomycosis wilt. The main signs are browning of shoots, twisting and falling of leaves starting from the crown. In this case, individual branches must be cut and burned, and if the entire bush is affected, then you will have to part with it. Prevention will help to partly avoid the problem. Carry out periodic watering under the root with preparations "Trichodermin", "Fitosporin", "Maxim" / "Healthy Earth". Start immediately after purchase - in a container. Remember that harmful fungi love waterlogged soil. Draw your own conclusions. nine0005

A little about shaping

Now, at the end of June-beginning of July, the deadline for pruning is coming. Forming in order to make the bushes thicker and more compact should have been carried out in early May. Therefore, it is impossible to pull, because new shoots should not only grow, but also mature, especially since the results of wintering have long been clear. What is frozen and withered - we cut without sparing. This is especially true of deciduous and semi-evergreen rhododendrons.

Therefore, it is impossible to pull, because new shoots should not only grow, but also mature, especially since the results of wintering have long been clear. What is frozen and withered - we cut without sparing. This is especially true of deciduous and semi-evergreen rhododendrons.

You will also have to resort to pruning evergreen species if their leaves are badly damaged by frost or disease. Rhododendron will sooner or later throw them off, and ugly bare branches with young thin shoots on tops will remain. It is better not to pull, but to shorten them by half or even shorter than their length. If you do not have time until mid-July with pruning, you will have to postpone this operation until spring. nine0005

And a little about nutrition

Rhododendrons are now actively growing young shoots and are starting to form flower buds for future flowering. Feed them with specialized fertilizer - about two-thirds of the recommended dose. This, above all, is necessary for those bushes that pleased you with lush and abundant flowering. Deadline - until the end of the first decade of July. Further, until mid-August, do not carry out any top dressing, only water.

Deadline - until the end of the first decade of July. Further, until mid-August, do not carry out any top dressing, only water.

I hope you find my advice helpful. Because a beautiful garden is real! Until we meet again on the pages of the series of articles “Ambulance for rhododendrons”.

Subscribe to our newsletter to be the first to know about new articles and promotions!

How to prune rhododendrons in spring and autumn after flowering

Contents

- 1 Is it possible to prune rhododendrons

- 2 Why prune rhododendrons

- 3 When is the best time to prune rhododendrons

- 4 How to trim the rhododendron

- 4.1 How to trim the rhododendrons in the spring

- 4.2 How to cut the rhododendron after flowering

- 4.3 How to cut the rhododendron for the winter

- 5 Tips

- 6 ° Better for a chic lively bouquet with an abundance of blooming flowers than a rhododendron.

These tree-like shrubs will not leave anyone indifferent during the flowering period and are not unreasonably considered rather capricious and fastidious in care. At the same time, trimming rhododendrons is no more difficult than other flowering perennials. Although, depending on the variety grown, these amazing beauties in pruning have their own characteristics and subtleties. nine0005

These tree-like shrubs will not leave anyone indifferent during the flowering period and are not unreasonably considered rather capricious and fastidious in care. At the same time, trimming rhododendrons is no more difficult than other flowering perennials. Although, depending on the variety grown, these amazing beauties in pruning have their own characteristics and subtleties. nine0005 Is it possible to prune rhododendrons

It is widely believed that rhododendrons do not need pruning, because they are genetically inherent in the desire for an almost ideal bush shape. And many novice gardeners are so sensitive to their promising plant pets that they get scared at the very thought that they need to pick up a pruner and cut something off from the most valuable specimen of rhododendron.

In fact, the experience of many gardeners, who have been growing various types of rhododendrons in their garden for many years, shows that rhododendrons are not only possible, but also necessary.

Like absolutely all plants, they absolutely need regular sanitary pruning. Many varieties also need to correct the form of growth. And more mature plants cannot escape from rejuvenating pruning. It can sometimes be replaced only by a complete replacement of the bush. But not every gardener is ready to easily say goodbye to his pet, who has delighted him with his flowering for many years, only because he has completely lost his shape. nine0005

Like absolutely all plants, they absolutely need regular sanitary pruning. Many varieties also need to correct the form of growth. And more mature plants cannot escape from rejuvenating pruning. It can sometimes be replaced only by a complete replacement of the bush. But not every gardener is ready to easily say goodbye to his pet, who has delighted him with his flowering for many years, only because he has completely lost his shape. nine0005 But in order not to bring your blooming pets to such a state, it is better to track all the nuances of possible incorrect growth of bushes every year and help them by forming an attractive crown with the help of pruning.

On the other hand, rhododendrons, unlike many other ornamental shrubs and trees, do not always require mandatory pruning. Indeed, even during transplantation, thanks to a small and compact root system, their roots do not stop their activity for a moment. This means that when moving shrubs with a whole root ball, they do not need the subsequent traditional shortening of the branches in order to balance the "bottoms" and "tops" of plants.

nine0005

nine0005 Why you need to prune rhododendrons

As in the case of almost any representatives of the plant kingdom, rhododendron pruning helps to solve many different problems:

- it serves as a preventive measure for various diseases and prevents pests from penetrating deep into branches or trunks;

- enhances growth and branching;

- helps the bushes perform at their best during flowering;

- increases the decorative effect of plants and reduces natural imperfections; nine0090

- allows you to enjoy the abundant and colorful flowering of your favorite bushes every year;

- helps prolong the life and beauty of many aging specimens.

When is the best time to prune rhododendrons

The most appropriate timing for prune rhododendrons depends most of all on the purpose for which this or that procedure is carried out. It is most optimal for most varieties to carry out different types of pruning at the very beginning of spring, even before the buds awaken.

In some cases, this must be done in late spring or early summer. Most rhododendrons require special pruning after flowering. Finally, it is allowed to prune in the autumn, before the onset of winter cold. nine0005

In some cases, this must be done in late spring or early summer. Most rhododendrons require special pruning after flowering. Finally, it is allowed to prune in the autumn, before the onset of winter cold. nine0005 How to prune a rhododendron

There is no single standard technique for prune any rhododendron. The type, degree and even the time interval for pruning is chosen depending on the species (deciduous or evergreen) and the age of the plant.

All existing varieties of rhododendrons are usually divided into the following categories, which differ in the types of pruning applied to them:

- deciduous small-leaved;

- deciduous and semi-evergreen large-leaved;

- evergreen small-leaved;

- evergreen large-leaved.

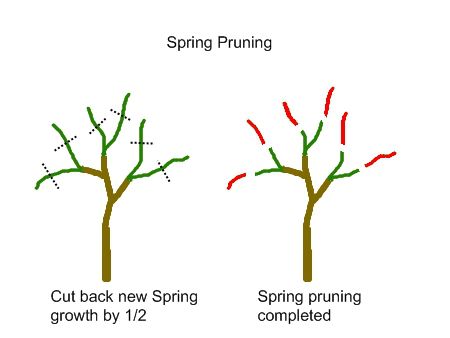

For plants of the first group, it is very important to carry out annual pinching of the tips of young shoots from the very first years after planting in late May or early June to form a dense and beautiful crown.

In autumn, and throughout the season, you can ruthlessly remove all too frail and underdeveloped branches, as well as shoots growing towards the center of the crown. Anti-aging pruning for shrubs of this group can be carried out 1 time in 5-7 years. nine0005

In autumn, and throughout the season, you can ruthlessly remove all too frail and underdeveloped branches, as well as shoots growing towards the center of the crown. Anti-aging pruning for shrubs of this group can be carried out 1 time in 5-7 years. nine0005 Attention! For a group of shrubs with large leaves, it can be important to wait for bud break and then cut off shoots that have not survived wintering.

For rhododendrons of the third group with small evergreen leaves, shaping pruning is especially important, which stimulates the formation of many young branches. With a strong desire, these varieties can be given almost any shape by trimming. Even form neat attractive "balls" from them. True, this requires a great deal of regular effort and attention on the part of the gardener throughout the year and is best done in warmer regions with mild winters. nine0005

In large-leaved evergreen species, very elongated and bare shoots are usually shortened in early spring to stimulate lateral branching.

Anti-aging pruning in large-leaved rhododendrons is carried out no more often than after 12-16 years.

Anti-aging pruning in large-leaved rhododendrons is carried out no more often than after 12-16 years. How to prune rhododendrons in spring

In early spring, before the buds swell, they usually do:

- sanitary;

- start;

- forming;

- rejuvenating pruning of rhododendrons. nine0090

Under the conditions of the middle zone, this period usually occurs in the second half of March or the beginning of April.

After the main snowmelt, it becomes approximately clear how the bushes endured the winter. Sanitary pruning of rhododendrons consists, first of all, in the removal of completely broken shoots, which are cut off just below the break. If the branch is not completely broken off, then if you wish, you can try to save it. To do this, the fracture site is tied with a polyethylene tape, and the shoot itself is tied to the upper branches or a supporting support is placed. nine0005

In deciduous rhododendrons, during severe winters, the bark may crack on individual shoots.

In these cases, it is necessary to cut off all damaged branches to a living place.

In these cases, it is necessary to cut off all damaged branches to a living place. Sanitary pruning also includes the removal of dry and frozen branches and leaves. But in many deciduous varieties it is not so easy to identify them before the buds swell. Therefore, you can wait a bit and prune later, after the leaves bloom.

Initial pruning is usually carried out after the purchase and transplantation of young shrubs to a new location. For evergreen types, it is usually not necessary. But deciduous bushes, if desired, can immediately be given an eye-catching shape. nine0005

Spring pruning of rhododendrons is often carried out to form a decorative crown. At the same time, either strongly protruding branches are removed, or those that grow deep into the crown and thicken it unnecessarily. As mentioned above, in deciduous types, it is recommended to additionally pinch young shoots, especially at a young age.

Anti-aging pruning is started when the rhododendron bushes grow so large that they block part of the path on the path or shade the windows of the living quarters.

In this case, you should not cut branches that are more than 3-4 cm thick, otherwise the bushes may die. Especially tender are the evergreen large-leaved varieties of rhododendrons. The places of cuts must be covered with a special garden paste or var. Already after 20-25 days, dormant buds may awaken on the branches below the cut and the bush will begin to grow with fresh shoots. nine0005

In this case, you should not cut branches that are more than 3-4 cm thick, otherwise the bushes may die. Especially tender are the evergreen large-leaved varieties of rhododendrons. The places of cuts must be covered with a special garden paste or var. Already after 20-25 days, dormant buds may awaken on the branches below the cut and the bush will begin to grow with fresh shoots. nine0005 The next year, the restoration of decorativeness and lush flowering is already possible.

It happens that it is necessary to carry out a strong rejuvenation by cutting branches almost to a stump. In this embodiment, the branches are cut at a distance of 30-40 cm from the ground. But you should not cut the entire bush at once. Deciduous species may be able to withstand such pruning, but evergreens have a chance not to survive it and not recover. Therefore, they usually cut about half of the bush in order to complete what they started next year. nine0005

How to prune a rhododendron after flowering

If you provide rhododendrons with competent and appropriate care throughout the season, they will delight with abundant flowering and fruiting.

But it was noticed that in this case the plants have some periodicity in flowering. Because they spend too much energy on the formation of fruits and seeds. If the bushes are grown solely for the sake of lush and beautiful inflorescences, then immediately after flowering they must be carefully broken out or cut off. Usually, a faded inflorescence is taken with two or three fingers and slightly bent to the side. It breaks easily. You just need to look carefully so as not to accidentally hurt the young shoots that form at the very base of the inflorescences. nine0005

But it was noticed that in this case the plants have some periodicity in flowering. Because they spend too much energy on the formation of fruits and seeds. If the bushes are grown solely for the sake of lush and beautiful inflorescences, then immediately after flowering they must be carefully broken out or cut off. Usually, a faded inflorescence is taken with two or three fingers and slightly bent to the side. It breaks easily. You just need to look carefully so as not to accidentally hurt the young shoots that form at the very base of the inflorescences. nine0005 As a result, all available nutrient reserves in the plant will go not to the formation of seeds, but to the laying of new flowering buds and the formation of new shoots. In addition, instead of one, two or three new young shoots are usually formed at the site of the inflorescence.

How to prune a rhododendron for the winter

In winter, rhododendrons are only cut for sanitary and sometimes rejuvenating pruning.

In terms of time, it most often falls on the end of September or the first half of October. Depending on the region, this should take place a few weeks before the onset of a hard frost and 2 weeks after the last feeding. nine0005

In terms of time, it most often falls on the end of September or the first half of October. Depending on the region, this should take place a few weeks before the onset of a hard frost and 2 weeks after the last feeding. nine0005 Pruning of rhododendrons in autumn is most often carried out in order to reduce the height of the bushes and ensure their full wintering under shelters.

Advice from Experienced Gardeners

In order to get the desired result from pruning rhododendrons, it is useful to listen to the opinions of experienced gardeners who have been successfully growing this luxurious shrub for many years.

- After any pruning, even sanitary, rhododendron bushes must be watered abundantly and fed with a complex set of fertilizers. The only exception is autumn pruning. nine0090

- It is best to prune the bushes on a regular basis, making sure the plants are in good shape every year. If for some reason the rhododendron has not been cut for a long time, then you should not carry out cardinal pruning within one season.

Learn more