Fruit tree growth

Fruit Tree Care: Planting Fruit Trees

Few things in life bring the same satisfaction as planting fruit trees. Learn to avoid future problems by following simple planning steps before you plant.

When it comes to planting fruit trees, we can never stress enough the importance of the planning stage. This includes choosing the best spot for your new planting above the ground and below the ground. We highly recommend that you contact your local utility department before digging to prevent damage to cables, pipes, and other underground structures.

Too often we encounter troubles because we act first and think later. That’s why, when planting an orchard or even a few trees in the back yard, it’s a good idea to take a step back and visualize how our efforts will look 10 years from now. Remember, the time difference between a vegetable garden and productive fruit trees can be years! It's also well worth the wait, so, to start things off right, let’s avoid future problems by considering a few key things before planting.

I. The Planting Site

Have you chosen a place free of interference? Is it far enough from power lines, sewer lines, sidewalks, etc.? Visualize your tree 10 years from now in the location you've chosen, and ask yourself those questions.

Questions to Ask

- What is the mature height & width of my tree?

- Is the planting site far enough away from power lines? Sewers? Sidewalks?

- Will the tree branches interfere with other trees growing nearby?

- Does my planting site get 5-8 hours of sunlight?

- Is my planting site well-drained, or does it hold water?

- Does my planting site have fertile soil, or will I need to amend it with a medium like coco-fiber or compost?

If your tree could talk, it would ask for a well-drained, fertile location with plenty of sunlight. While a full day's sun is great, trees can still thrive and produce on a half-day's light; and most trees are forgiving of imperfect soil conditions. If your ground is a little heavy, consider using our coco-fiber medium. Just drop the brick into 1 1/3 gallons of warm/hot water, 30 minutes before planting. When refilling the hole, work the coco-fiber into the soil and finish planting. This will give the root system air and allow for water absorption as the roots develop.

Just drop the brick into 1 1/3 gallons of warm/hot water, 30 minutes before planting. When refilling the hole, work the coco-fiber into the soil and finish planting. This will give the root system air and allow for water absorption as the roots develop.

Planting Tips

- Fill in planting hole with top soil first.

- Amend bottom soil with a good medium, either coco-fiber or organic compost.

- Plant graft about 2-3 inches above ground level.

- Keep the tree straight.

- Tamp the soil to remove air pockets.

- When finished, prune & water well. (only prune if your tree has not already been pre-pruned)

- Stand back & enjoy!

II. Digging the Hole

When digging the hole, a good rule of thumb is to remove a space nearly twice the width and depth of the roots. You don't want the roots cramped or circled. The area you loosen is the area the roots will quickly grow into to anchor and sustain the tree's top. This simple task helps determine both how good the foundation will be years later and how well the plant utilizes two much-needed ingredients: air and water.

III. Planting the Tree

The Soil

You know the soil you dug up first, right underneath the grass? When refilling your planting hole, it's always best to place that soil in first. It's usually more fertile, as well as more porous, and when placed down near the roots, it will help the tree grow better. The remaining soil (from the bottom of the dug hole) is heavier and works well when mixed with the Coco-Fiber Medium. From top to bottom, work the soil with your hands to avoid large clods that create air pockets.

Graft Placement

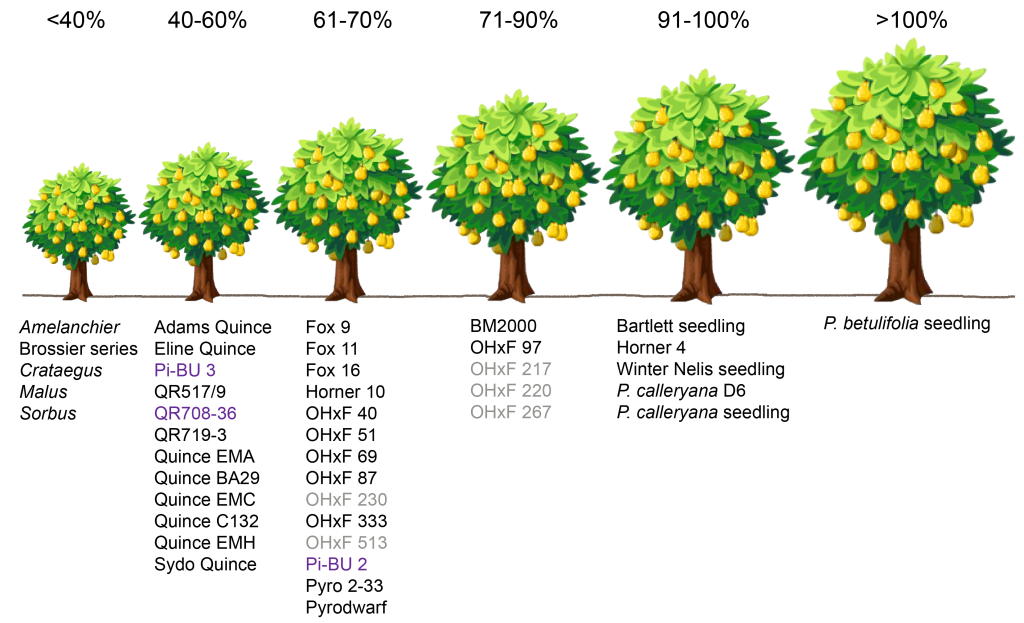

When you refill your planting hole, hold the tree up a bit to allow loose soil to fall beneath, as well as around the sides of, the roots. Center its position so there is adequate space on all sides for the root system to grow out. If you are planting a dwarf or semi-dwarf apple tree, hold the bud union up above the refill line – this is the "bump" above the root system of the tree where the rootstock was grafted to the varietal top. If given the opportunity, grafted apple trees will self-root; if the variety self-roots, you’ll lose the size-restrictive nature of the rootstock. (Did you know the rootstock is responsible for the mature size of your tree, i.e. dwarf, semi-dwarf, standard? We don't want to lose that sizing characteristic — it would definitely throw a rock in your long-term plan!)

If given the opportunity, grafted apple trees will self-root; if the variety self-roots, you’ll lose the size-restrictive nature of the rootstock. (Did you know the rootstock is responsible for the mature size of your tree, i.e. dwarf, semi-dwarf, standard? We don't want to lose that sizing characteristic — it would definitely throw a rock in your long-term plan!)

Finishing Touches

Through the process, keep the tree straight (perpendicular) and, upon finishing, tamp the tree in with your foot to remove air spaces and seal it in. If the tree is planted on a slope, create a slight berm on the lower side to utilize water throughout the summer. If it’s not pre-pruned before you plant it, be sure to prune your tree, and water it well.

There are few things in life that have the sustainability and bring the same satisfaction as growing a fruit tree. The years following will be spent measuring the tree’s progress and reaping its rewards. That’s a "10-year" vision – yep! I saw the future before I began; how about you?

— Elmer Kidd, Stark Bro's Chief Production Officer (retired)

Shop All Fruit Trees »

All About Growing Fruit Trees – Mother Earth News

(For details on growing many other vegetables and fruits, visit our Crop at a Glance collection page. )

)

No plants give sweeter returns than fruit trees. From cold-hardy apples and cherries to semi-tropical citrus fruits, fruit trees grow in nearly every climate. Growing fruit trees requires a commitment to pruning and close monitoring of pests, and you must begin with a type of fruit tree known to grow well in your area.

Choose varieties recommended by your local extension service, as some varieties need a certain level of chill hours (number of hours below 45 degrees Fahrenheit).

Types of Fruit Trees to Try

Even fruit trees described as self-fertile will set fruit better if grown near another variety known to be a compatible pollinator. Extension publications and nursery catalogs often include tables listing compatible varieties.

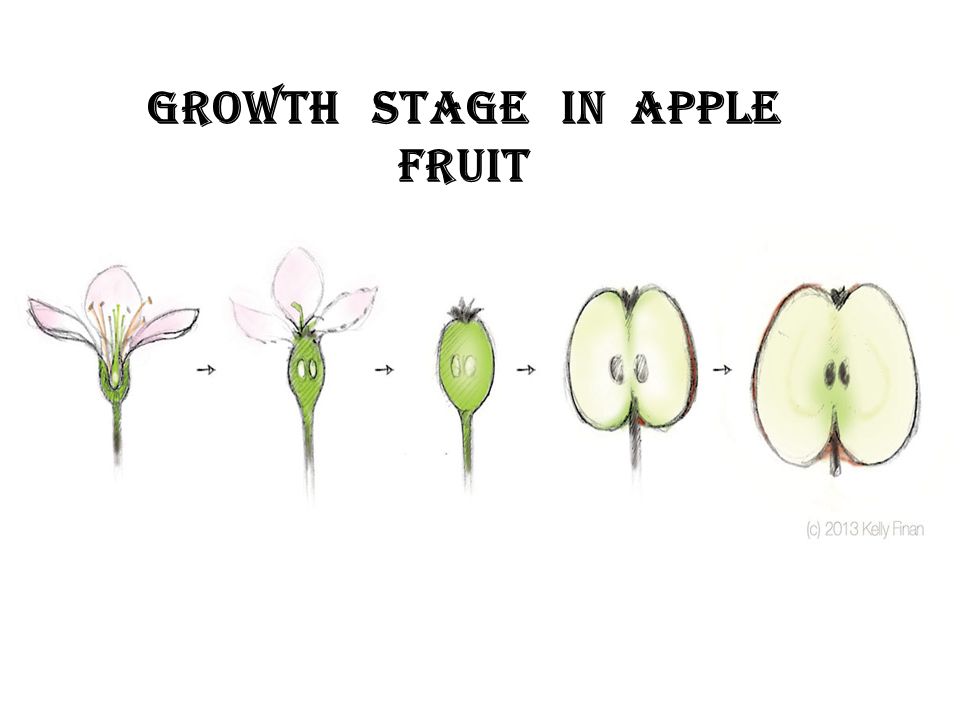

Apples (Malus domestica) are the most popular tree fruits because they are widely adapted, relatively easy to grow and routine palate-pleasers. The ideal soil pH for apples is 6.5, but apple trees can adjust to more acidic soil if it’s fertile and well-drained. Most apple varieties, including disease-resistant ‘Freedom’ and ‘Liberty,’ are adapted to cold-hardiness Zones 4 to 7 (if you don’t know your Zone, see “Know Your Cold-Hardiness Zone” later in this article), but you will need low-chill varieties, such as ‘Anna’ and ‘Pink Lady,’ in mild winter climates. No matter your climate, begin by choosing two trees that are compatible pollinators to get good fruit set. Mid- and late-season apples usually have better flavor and store longer compared with early-season varieties.

Most apple varieties, including disease-resistant ‘Freedom’ and ‘Liberty,’ are adapted to cold-hardiness Zones 4 to 7 (if you don’t know your Zone, see “Know Your Cold-Hardiness Zone” later in this article), but you will need low-chill varieties, such as ‘Anna’ and ‘Pink Lady,’ in mild winter climates. No matter your climate, begin by choosing two trees that are compatible pollinators to get good fruit set. Mid- and late-season apples usually have better flavor and store longer compared with early-season varieties.

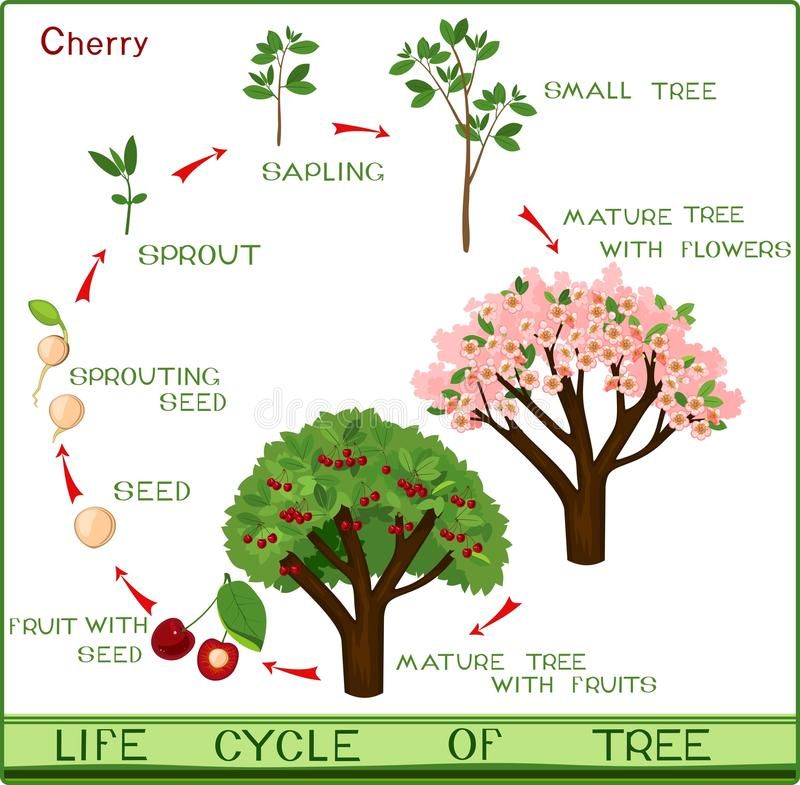

Cherries (Prunus avium (sweet) and P. cerasus (sour)) range in color from sunny yellow to nearly black and are classified in two subtypes: compact sweet varieties, such as ‘Stella,’ and sour or pie cherries, such as ‘Montmorency’ and ‘North Star.’ Best adapted to Zones 4 to 7, cherry trees need fertile, near-neutral soil and excellent air circulation. Growing 12-foot-tall dwarf cherry trees of either subtype will simplify protecting your crop from diseases and birds, because the small trees can be covered with protective netting or easily sprayed with sulfur or kaolin clay.

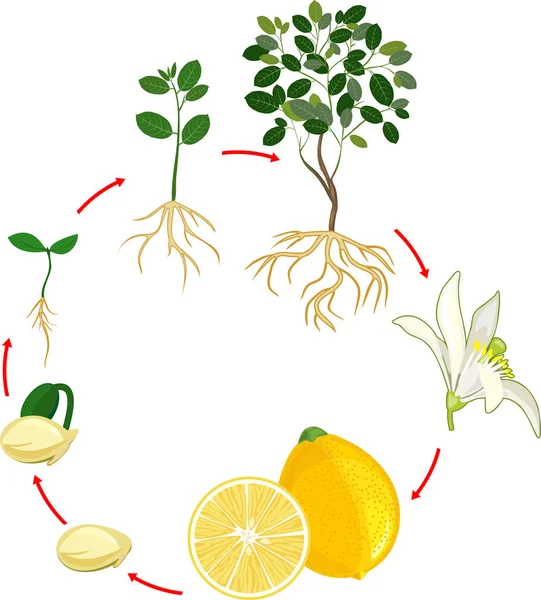

Citrus fruits (Citrus hybrids), including kumquat, Mandarin orange, satsuma and ‘Meyer’ lemon, are among the easiest fruit trees to grow organically in Zones 8b to 10. Fragrant oils in citrus leaves and rinds provide protection from pests, but cold tolerance is limited. ‘Nagami’ kumquat, ‘Owari’ satsuma and ‘Meyer’ lemon trees may occasionally need to be covered with blankets when temperatures drop below freezing, but winter harvests of homegrown citrus fruits will be worth the trouble.

Peaches and nectarines (Prunus persica) are on everyone’s want list, but growing these fruit trees organically requires an excellent site, preventive pest management and some luck. More than other fruit trees, peach and nectarine trees need deep soil with no compacted subsoil or hardpan. Peaches and nectarines are best adapted to Zones 5 to 8, but specialized varieties can be grown in colder or warmer climates. Peach and nectarine trees are often short-lived because of wood-boring insects, so plan to plant new trees every 10 years.

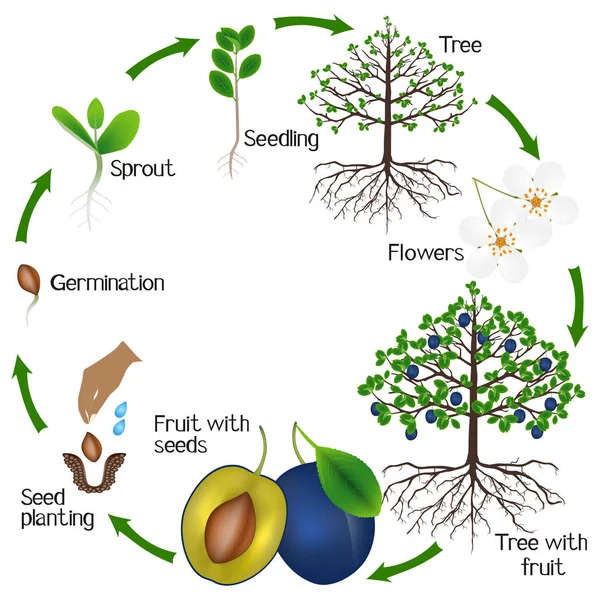

Plums (Prunus species and hybrids) tend to produce fruit erratically because the trees often lose their crop to late freezes or disease. In good years, plum trees will yield heavy crops of juicy fruits, that vary in color from light green to dark purple. Best adapted to Zones 4 to 8, plum trees need at least one compatible variety nearby to ensure good pollination. In some areas, selected native species, such as beach plums in the Northeast or sand plums in the Midwest, may make the best homestead plums.

Pears (Pyrus species and hybrids) are slightly less cold-hardy than apples but are easier to grow organically in a wide range of climates. In Zones 4 to 7, choose pear varieties that have good resistance to fire blight, such as ‘Honeysweet’ or ‘Moonglow.’ In Zones 5 to 8, Asian pear trees often produce beautiful, crisp-fleshed fruits if given routine care. Most table-quality pears should be harvested before they are fully ripe.

How to Plant

The best time to plant fruit trees in Zones 3 through 7 is early spring, after the soil has thawed. Fruit trees that are set out just as they emerge from winter dormancy will rapidly grow new roots. In Zones 8 to 10, plant new trees in February. Choose a sunny site with fertile, well-drained soil that’s not in a low frost pocket. Dig a planting hole that’s twice the size of the root ball of the tree. Carefully spread the roots in the hole, and backfill with soil. Set trees at the same depth at which they grew at the nursery, taking care not to bury any graft union (swollen area) that’s on the main trunk. Water well, and install a trunk guard made of hardware cloth or spiral plastic over the lowest section of the trunk to protect it from insects, rodents, sunscald and physical injuries. Stake the tree loosely to hold it steady. Mulch over the root zone of the planted trees with wood chips, sawdust or another slow-rotting mulch. Water particularly well during any dry spells for the first two years.

One year after planting, fertilize fruit trees in spring by raking back the mulch and scratching a balanced organic fertilizer into the soil surface (follow application rates on the product’s label). Then add a wood-based mulch to bring the mulch depth up to 4 inches in a 4-foot circle around the tree. After two years, stop using trunk guards and instead switch to coating the trunks with white latex paint to defend against winter injuries. Add sand to the paint to deter rabbits and voles.

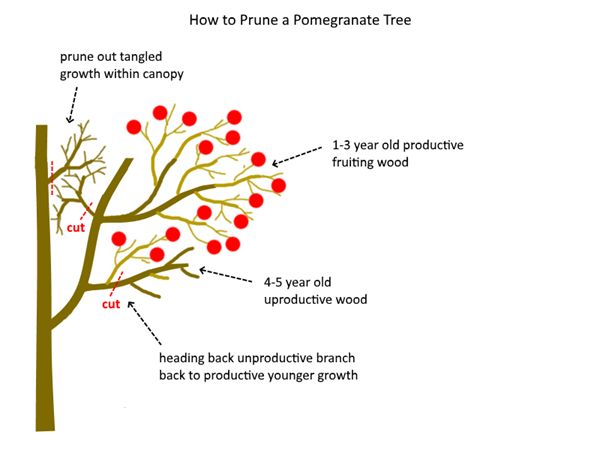

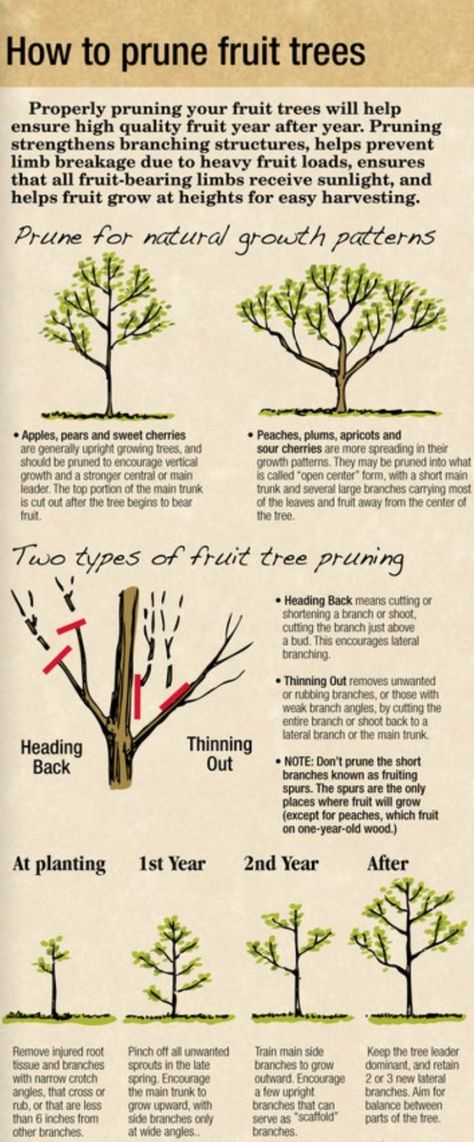

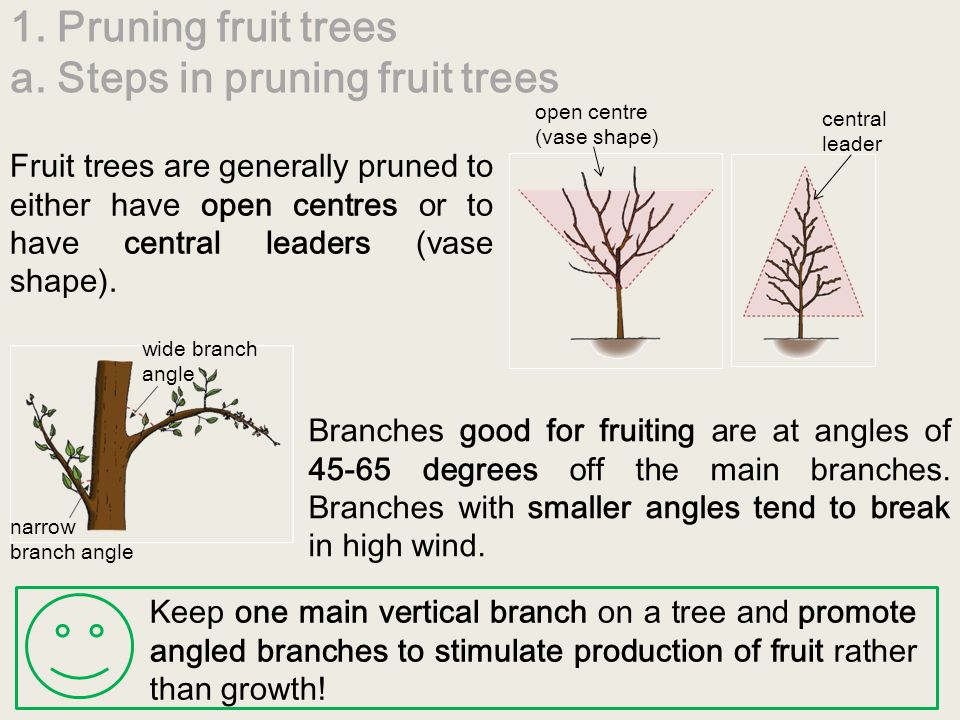

Pruning Fruit Trees

Pruning is a key aspect of growing fruit trees. The goal of pruning fruit trees is to provide the leaves and fruit access to light and fresh air. The ideal branching pattern varies with species, and some apple and pear trees can be pruned and trained into fence- or wall-hugging espaliers to save space. Begin pruning fruit trees to shape them in their first year, and then prune annually in late winter, before the buds swell. Pruning a little too much questionable growth is better than removing too little.

Many fruit trees set too much fruit, and the excess should be thinned. Asian pear trees should have 70 percent of their green fruits snipped off when the pears are the size of a dime, and apples should be thinned to 6 inches apart before the fruits are the size of a quarter. When any type of fruit tree is holding a heavy crop, thinning some of the green fruits will increase fruit size, reduce limb breakage and help prevent alternative bearing (a tree setting a crop only every other year).

Harvesting and Storage

With the exception of pears, tree fruits should be harvested just as they approach full ripeness and then kept chilled to slow spoilage. The flavor of most apples improves after a few weeks in cold storage, so a second refrigerator or a root cellar may be useful. Apples and pears can be kept for several months in a refrigerator, but softer stone fruits (cherries, nectarines, peaches and plums) must be canned, dried, frozen or juiced within a few days of harvest for long-term storage.

Pest and Disease Tips

Some types of fruit crops attract a large number of insect pests and can succumb to several widespread diseases for which no resistant varieties are available. For example, all of the stone fruits are frequently affected by brown rot, a fungal disease that overwinters in mummified fruit. Apply early-season sulfur sprays to suppress brown rot and other common diseases. Some apples have good genetic resistance to scab and rust, but you will still need to manage insect pests, such as codling moths.

Allowing chickens to forage beneath fruit trees can help suppress insects. Many organic growers also keep their fruit trees coated with kaolin clay during the growing season to repel pests.

In the Kitchen

Managing the hefty harvests from mature fruit trees will require a range of food-preservation skills. Manual fruit-processing equipment, such as a cherry pitter (see Slideshow) or an apple peeler/corer, can be excellent investments. At each picking, a number of bruised fruits will need attention right away, while you can refrigerate and forget about sound fruits until your next preservation project. In addition to making jams, jellies and chutneys, try freezing or canning homemade fruit juices. Packets of frozen fruit are handy for baking or in smoothies, and dried fruit can be quickly rehydrated in warm water or munched as a snack.

In addition to making jams, jellies and chutneys, try freezing or canning homemade fruit juices. Packets of frozen fruit are handy for baking or in smoothies, and dried fruit can be quickly rehydrated in warm water or munched as a snack.

Know Your Cold-Hardiness Zone

The “Zones” referred to in this article come from maps published by the United States Department of Agriculture that show the average minimum winter temperature for each region. Some types of fruit can tolerate more winter cold than others, so your area’s cold-hardiness is important to know before you choose which fruit trees to grow. If you don’t know your Zone, you can find it at the United States Department of Agriculture. If a mail-order nursery doesn’t tell you which Zone a crop is suited for, you should probably buy from another supplier.

Contributing editor Barbara Pleasant gardens in southwest Virginia, where she grows vegetables, herbs, fruits, flowers and a few lucky chickens. Contact Barbara by visiting her website.

Contact Barbara by visiting her website.

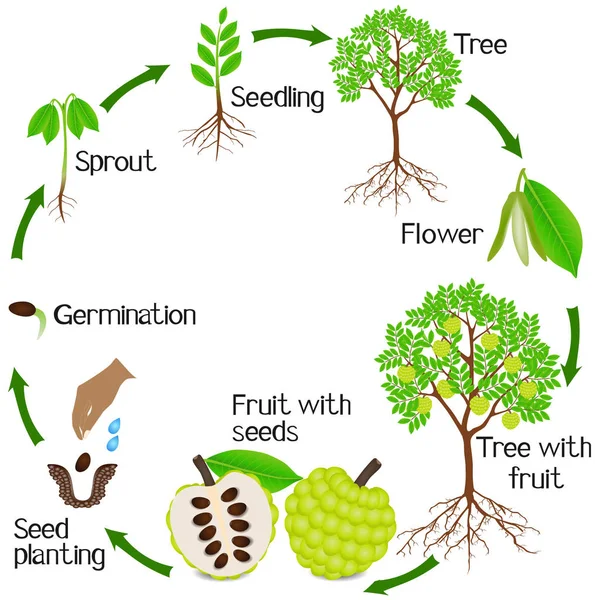

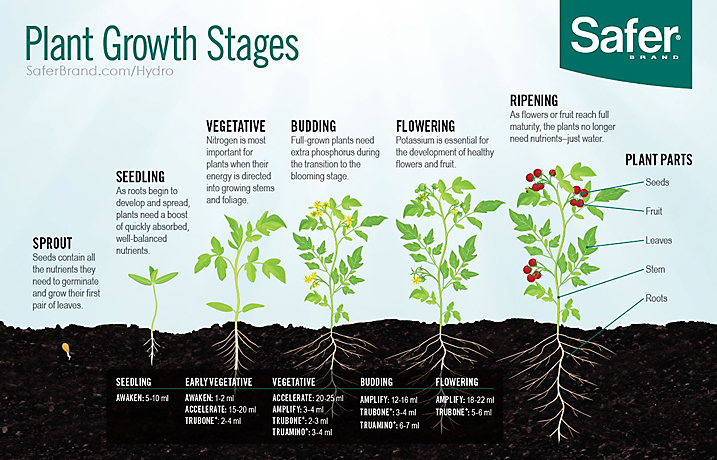

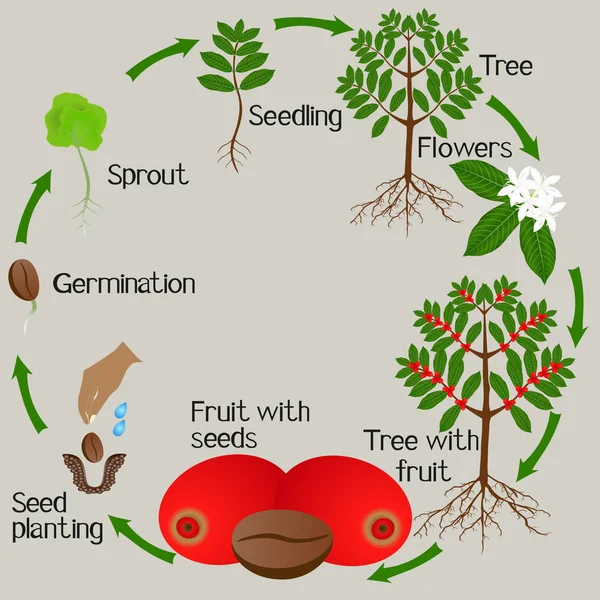

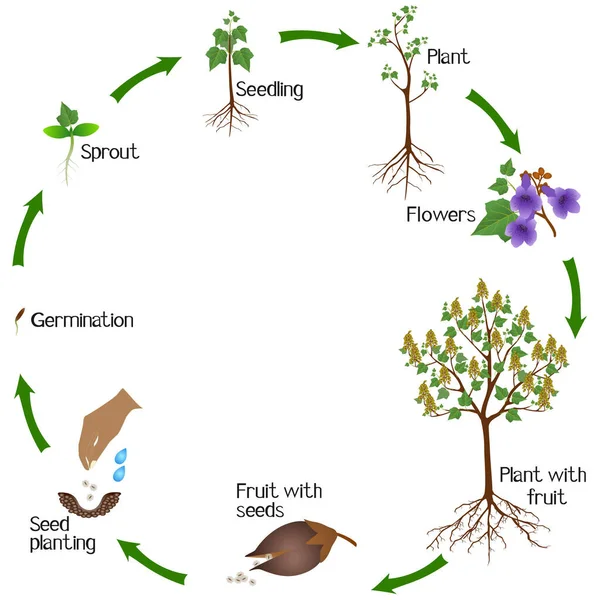

Growth and development of fruit trees. The life of fruit plants.

Growth and development of fruit trees

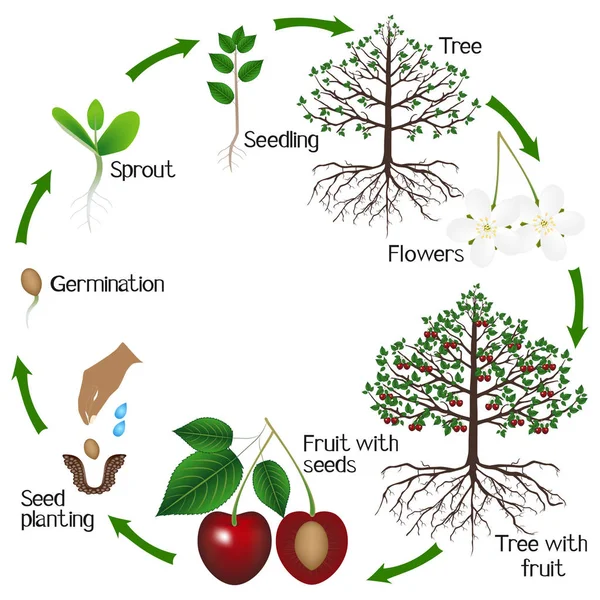

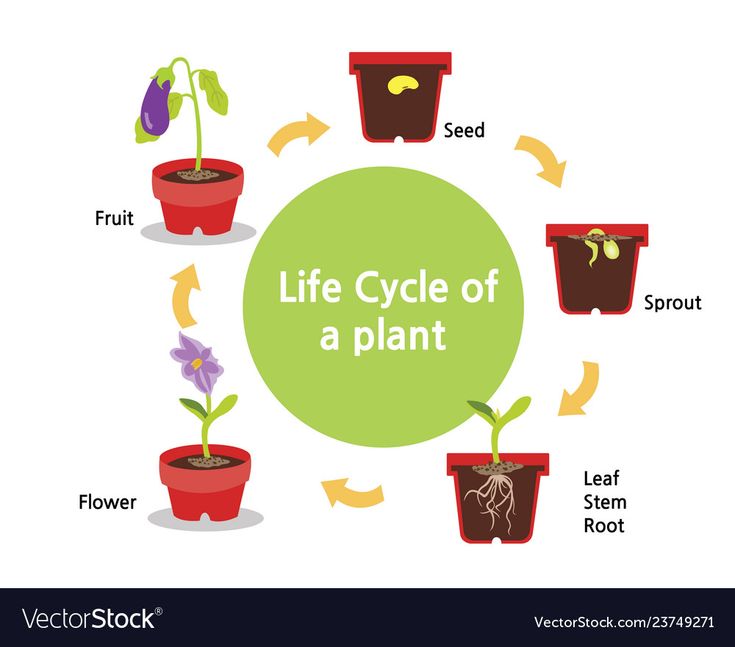

The life of fruit plants changes throughout the year depending on external conditions. There are two periods: vegetation and dormancy.

The growing season begins in spring with bud break and ends in autumn with leaf fall. It is divided into several phenological phases: bud break, shoot growth and flowering, ovary formation and fruit development, formation of generative buds, tissue maturation. Phenophases are divided into their constituent phases. For example, in the flowering phenophase, phases are distinguished: inflorescence advancement, bud separation, the appearance of corollas, petal divergence, flowering, petal fall. nine0003

The passage of phenological phases is taken into account in the preparation and implementation of the calendar plan of agrotechnical work in the garden.

Phenophases occur in sequence and often overlap, such as shoot growth and fruit development. The duration of their passage is not the same. The longest phenophases of generative bud formation and fruit development. Sometimes phenophases are repeated (secondary growth and flowering). Any phase is dynamic. It has an initial development, complete and fading. nine0003

The duration of their passage is not the same. The longest phenophases of generative bud formation and fruit development. Sometimes phenophases are repeated (secondary growth and flowering). Any phase is dynamic. It has an initial development, complete and fading. nine0003

Bud opening begins in spring with their fragrance and ends with the formation of rosettes of leaves from vegetative buds and flowering. The beginning of the growing season is not the same for different breeds. Hazelnuts, dogwoods, almonds, peaches, apricots, currants, gooseberries begin to vegetate first; later than others, a pear and an apple tree. In some breeds, generative buds first bloom (hazelnuts, almonds, peach), in others, vegetative buds (quince, walnut).

The growth of shoots begins with the formation of a rosette of leaves after the opening of vegetative buds and ends with the formation of apical buds at the ends of the shoots. Shoot growth lasts 2-2.5 months in the middle zone of our country and 3-3. 5 months in the south. In fruit-bearing trees (third-fifth periods of life), it ends earlier (June-July), while in young trees it can continue until the end of the growing season (September-October). In wet summers, shoots grow longer than in dry ones. The phase of enhanced growth with a daily gain of 5-20 mm is short (15-40 days) and usually occurs in May and June. At this time, the main part of the vegetative mass is created, leaves are formed, and the tree needs large amounts of water and mineral nutrition, especially nitrogen. At the same time, prolonged growth of shoots in young trees should not be allowed so that the wood has time to mature and the branches do not freeze in winter. nine0003

5 months in the south. In fruit-bearing trees (third-fifth periods of life), it ends earlier (June-July), while in young trees it can continue until the end of the growing season (September-October). In wet summers, shoots grow longer than in dry ones. The phase of enhanced growth with a daily gain of 5-20 mm is short (15-40 days) and usually occurs in May and June. At this time, the main part of the vegetative mass is created, leaves are formed, and the tree needs large amounts of water and mineral nutrition, especially nitrogen. At the same time, prolonged growth of shoots in young trees should not be allowed so that the wood has time to mature and the branches do not freeze in winter. nine0003

Flowering begins with the protrusion of inflorescences after the opening of generative buds and ends with the fall of the petals.

The beginning and duration of this phenophase depend on the breed and varietal characteristics of plants, growing conditions, temperature and air humidity. Before all, hazelnuts begin to bloom, and then (successively) dogwood, almond, apricot, cherry plum, peach, cherry, plum, cherry, pear, walnut, apple tree, quince. Flowering time is 7-18 days. In hot and dry weather, it passes faster, and in cold, damp weather it drags on. In late and friendly spring, fruit trees bloom almost simultaneously. Flowering is considered massive when 75% of the flowers bloom. nine0003

Before all, hazelnuts begin to bloom, and then (successively) dogwood, almond, apricot, cherry plum, peach, cherry, plum, cherry, pear, walnut, apple tree, quince. Flowering time is 7-18 days. In hot and dry weather, it passes faster, and in cold, damp weather it drags on. In late and friendly spring, fruit trees bloom almost simultaneously. Flowering is considered massive when 75% of the flowers bloom. nine0003

The normal passage of the flowering phenophase depends on the amount of reserve nutrients accumulated since autumn and the conditions in which it occurs. The gardener must protect the flowers from frost, damage by pests and diseases, take care of the importation of bees into the garden for good pollination of the flowers. It is necessary to monitor the humidity of the soil and air: in wet rainy weather, do not irrigate before flowering, but in dry windy, on the contrary, water the garden to moisten the soil and the surface layer of air.

nine0002 The formation of ovaries and fruit development begins with the formation of a zygote after the fertilization of the flower and ends with the ripening of the fruit. In early ripening breeds and varieties (strawberries, early varieties of sweet cherries), this phenophase lasts about one month, in early apple varieties - 2 months, in winter varieties of pome trees - 4-5 months.

In early ripening breeds and varieties (strawberries, early varieties of sweet cherries), this phenophase lasts about one month, in early apple varieties - 2 months, in winter varieties of pome trees - 4-5 months. Not all flowers bear fruit. Apple and pear trees with abundant flowering use only 5-20% of the total number of flowers to create a normal crop. With moderate flowering, the percentage of ovary formation increases and the trees consume reserve nutrients more economically. Flowers and young fruits (ovaries) fall off due to the imperfection of individual generative buds, from unfavorable conditions, poor fertilization of flowers, insufficient mineral nutrition and water supply, and for other reasons. The flowers fall off during flowering, and the developing young fruits until the beginning of their maturation. Shedding of young fruits occurs in waves. The first (main) increase in shedding is observed immediately after flowering, the second - after one to two weeks, the third (June) - after two to three weeks. The sooner and more amicably showered excess young fruits, the better for the fruit tree. In this case, the remaining fruits develop normally and become larger. nine0003

The sooner and more amicably showered excess young fruits, the better for the fruit tree. In this case, the remaining fruits develop normally and become larger. nine0003

An increase in the mass of the fetus occurs until it is fully ripe, at first slowly, then intensely, and at the end its growth slows down again. When ripe, the fruits acquire the qualities characteristic of the variety (size, shape, color, aroma, etc.). The maturation of the seed and the pericarp does not always coincide. For example, in summer apples, the pericarp ripens earlier than the seeds, and in winter, on the contrary.

In the formation and development of fruits, care must be taken to ensure sufficient water supply and mineral nutrition of fruit trees and avoid any violations in agricultural technology. With excessive flowering and the formation of ovaries, sometimes chemical thinning of flowers or young fruits is carried out after flowering. nine0003

Formation (differentiation) of generative buds begins after the completion of shoot growth (most often in June-July) and lasts 30-40 days or more. At this time, the rudiments of all the organs of the flower are formed in the kidney. The beginning and duration of this phenophase depend on the breed, variety, rootstock, age and condition of the plants, weather conditions, and agricultural practices used. In pome breeds, the formation of generative buds begins from the third decade of June - in July, in stone fruits - in early to mid-June. Early-flowering varieties form generative buds earlier than late-flowering varieties. Dry and hot summer accelerates the beginning of the formation of flower buds. On annuli and bouquet twigs, they form earlier than on longer fruit-bearing branches or in the leaf axils of long shoots. nine0003

At this time, the rudiments of all the organs of the flower are formed in the kidney. The beginning and duration of this phenophase depend on the breed, variety, rootstock, age and condition of the plants, weather conditions, and agricultural practices used. In pome breeds, the formation of generative buds begins from the third decade of June - in July, in stone fruits - in early to mid-June. Early-flowering varieties form generative buds earlier than late-flowering varieties. Dry and hot summer accelerates the beginning of the formation of flower buds. On annuli and bouquet twigs, they form earlier than on longer fruit-bearing branches or in the leaf axils of long shoots. nine0003

In remontant varieties of strawberries, raspberries and other species that produce two or more harvests per year, generative buds are formed not only in the summer and autumn of the previous year, but also on the shoots of the current year. For the normal passage of the phenophase, a large amount of plastic substances (carbohydrates) is necessary. This is facilitated by good foliage of the crowns and optimal illumination of the leaves. To accelerate fruiting and increase the yield of young trees of late-fruiting varieties, special techniques are performed (spraying with retardants, tilting skeletal branches, pinching shoots, etc.). nine0003

This is facilitated by good foliage of the crowns and optimal illumination of the leaves. To accelerate fruiting and increase the yield of young trees of late-fruiting varieties, special techniques are performed (spraying with retardants, tilting skeletal branches, pinching shoots, etc.). nine0003

The maturation of tissues begins with the cessation of shoot growth and ends with yellowing and mass leaf fall. It is characterized by the cessation of cell division of the apical and lateral shoot meristems. In the storage tissues of branches and roots, starch, fats and other nutrients are deposited. A sign of tissue maturation is the appearance of a distinct border between wood and bark on the transverse section of the apical bud. Shoots with artificial bending slightly crackle.

This phenophase proceeds normally with a gradual decrease in air temperature (up to 15 C and below), shortened daylight hours and timely autumn cooling. Plants of northern and temperate latitudes shed their leaves earlier than those growing in the south. Normal yellowing and leaf fall are an indicator of good tissue maturation and accumulation of reserve nutrients. Before leaf fall, nutrients move from the leaves to the roots and branches, where they are deposited. Good maturation of tissues and a large supply of nutrients ensure high winter hardiness of plants and the successful development of spring and early summer phenophases. nine0003

Normal yellowing and leaf fall are an indicator of good tissue maturation and accumulation of reserve nutrients. Before leaf fall, nutrients move from the leaves to the roots and branches, where they are deposited. Good maturation of tissues and a large supply of nutrients ensure high winter hardiness of plants and the successful development of spring and early summer phenophases. nine0003

The task of agricultural technology of this phenophase includes: 1) timely suspension of growth processes, especially young and heavily pruned trees, by early termination of irrigation and application of nitrogen supplements; 2) to create the best conditions for the phytosynthesis of leaves and the vital activity of roots before leaf fall by watering, tillage, etc.; 3) remove the fruits from the tree in time to lengthen the phenophase and enable the tree to better prepare for winter.

The dormant period begins after leaf fall and continues in winter under natural conditions until the beginning of the growing season. It is divided into preliminary, deep and forced. Preliminary dormancy occurs in the kidneys and is observed at the end of the growing season. After the leaves fall at a temperature of 5-7 C and below, the plants enter into a deep (organic or natural) dormancy. During deep dormancy, great internal changes occur: the metabolic rate slows down sharply, cell division stops, starch content increases, etc. The plant does not leave its dormant state even under favorable external conditions and becomes the most winter-hardy. nine0003

It is divided into preliminary, deep and forced. Preliminary dormancy occurs in the kidneys and is observed at the end of the growing season. After the leaves fall at a temperature of 5-7 C and below, the plants enter into a deep (organic or natural) dormancy. During deep dormancy, great internal changes occur: the metabolic rate slows down sharply, cell division stops, starch content increases, etc. The plant does not leave its dormant state even under favorable external conditions and becomes the most winter-hardy. nine0003

The depth and duration of organic dormancy depend on the breed, variety, rootstock, condition and age of plants, external conditions and agricultural practices. The deepest period of dormancy is characterized by pome-bearing breeds, less stone fruits (apricot, peach, etc.). Separate parts of the fruit tree at different times go into a state of rest. The root neck is the last to enter a dormant state, therefore, in cold areas, it is recommended to spud it with soil to protect it from freezing. Later than other tissues, the cambium passes into a state of deep rest. nine0003

Later than other tissues, the cambium passes into a state of deep rest. nine0003

After deep dormancy, forced dormancy sets in, during which plant growth is retarded only by unfavorable external factors. It can easily be disturbed by creating the conditions necessary for vegetation (increasing temperature, improving lighting and humidity, etc.). This is widely used in the cultivation of strawberries and flowering plants in winter in greenhouses and greenhouses.

The rest period can be lengthened or shortened by spraying trees with physiologically active substances, early spring watering of gardens, summer pruning and other agricultural practices. nine0003

Stem growth and growth periods of fruit trees

Stem growth and growth periods of fruit trees

Growth in length occurs due to tissue division at points of growth and cell elongation. The increase in the thickness of the stem is carried out only due to the division of cambial cells. Growth in length and thickness occurs periodically.

Growth in length. In spring, fruit trees and shrubs begin to grow. Buds open, from which leaves, new shoots and flowers are formed. In the kidneys, under the protection of covering scales, capable of dividing (meristematic) tissues are preserved during the winter. In the spring, they begin to divide, due to which new growth begins on the axes of the branches, and especially from the apical buds. During the growth of new shoots, leaves are formed on them, and in the axils of the leaves - axillary, or lateral buds. nine0003

Places of laying leaves and places of formation of axillary buds are clearly visible already in winter on a longitudinal section of the growing point: when magnified, they are visible in the form of tubercles. Later, during growth, the zones located between the places of leaf formation stretch, forming internodes and increasing the distance between adjacent nodes (with leaves).

Depending on the location of the buds in the crown during the growing season, they form shoots with long or short internodes (long and short branches). By autumn, the growth of the shoots ends with the laying of the apical bud, which can be either leaf or flower. nine0003

By autumn, the growth of the shoots ends with the laying of the apical bud, which can be either leaf or flower. nine0003

The growth of fruit crops during the growing season is uneven, but, on the contrary, periodically changes. From the moment of bud break and until about the beginning of June, there is a very active development and rapid growth of shoots. Then, from mid-June, a phase of weak growth or even complete dormancy begins. From the end of July, secondary growth (ivan shoots) begins, which fades only by autumn. Sometimes, for example, due to improper pruning in the fall, a third growth period may begin, which is highly undesirable, since the shoots formed at this time cannot lignify well enough. Young trees with strong shoot growth are less affected by this growth cycle than older trees. nine0003

Growth in thickness. Young shoots growing in length due to the division of tissues of the growing point could not thicken if they did not develop along the entire length the meristimatic tissue, the cambium, that retains the ability to divide.