Arts and crafts architectural style

Arts & Crafts Architecture and How To Spot Arts & Crafts Homes

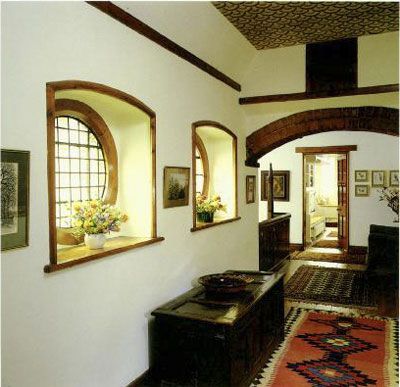

Architect Gary Brewer breathed new life into this Yonkers Foursquare, which he calls home.

Francis Dzikowsk

For many old-house observers, Arts & Crafts may be one of the most confusing architectural styles. The name sounds improbable—more like a Girl Scout merit badge than a house style. And what does an Arts & Crafts-style house look like anyway? Is it a Craftsman bungalow, a Foursquare with bracketed eaves, a quaint cottage, or perhaps an architect-designed Prairie house?

The answer: Yes.

Practically the only common factors to be found in all Arts & Crafts houses are those that encourage an informal but cultured lifestyle:

- an open floor plan

- natural materials such as stone, brick, and wood

- airy, light-filled rooms that encourage interaction with the outdoors

- the tasteful arrangement of a few well-designed, decorative, and useful objects

Arts & Crafts stained-glass window.

Eric Roth

The term Arts & Crafts refers to a broad social and artistic movement that took shape in Great Britain and Europe in the middle of the 19th century and then leapt the Atlantic to garner wild acclaim in the United States at the turn of the 20th century. It encompasses interior design, fine and decorative arts, printing and publishing (book design, illustrations, posters, and advertisements), jewelry and tableware, textiles and wallpaper, furniture and ceramics—and, oh yes, houses.

A Tasteful Standard

The 1901 Davenport House in River Forest, Illinois, was designed during Frank Lloyd Wright’s brief, little-known partnership with Webster Tomlinson, and resembles several other early Wright houses.

The Arts & Crafts movement began as a revolt against bad taste. And bad taste, Arts & Crafts devotees believed, was embodied in the flood of poorly designed, carelessly made, overly decorated, useless household goods that resulted from the Industrial Revolution. So much stuff, so little beauty and utility.

So much stuff, so little beauty and utility.

Tastemakers and social critics like England’s William Morris shuddered at the sight of it. “Have nothing in your houses that you do not know to be useful or believe to be beautiful,” Morris urged his readers. Well-designed, handcrafted objects were admirable; factory goods were an abomination.

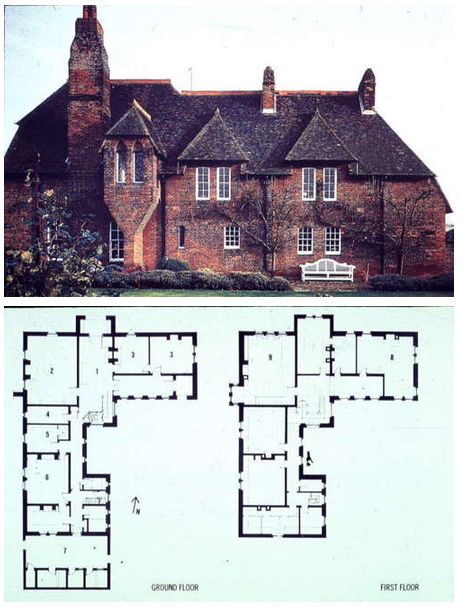

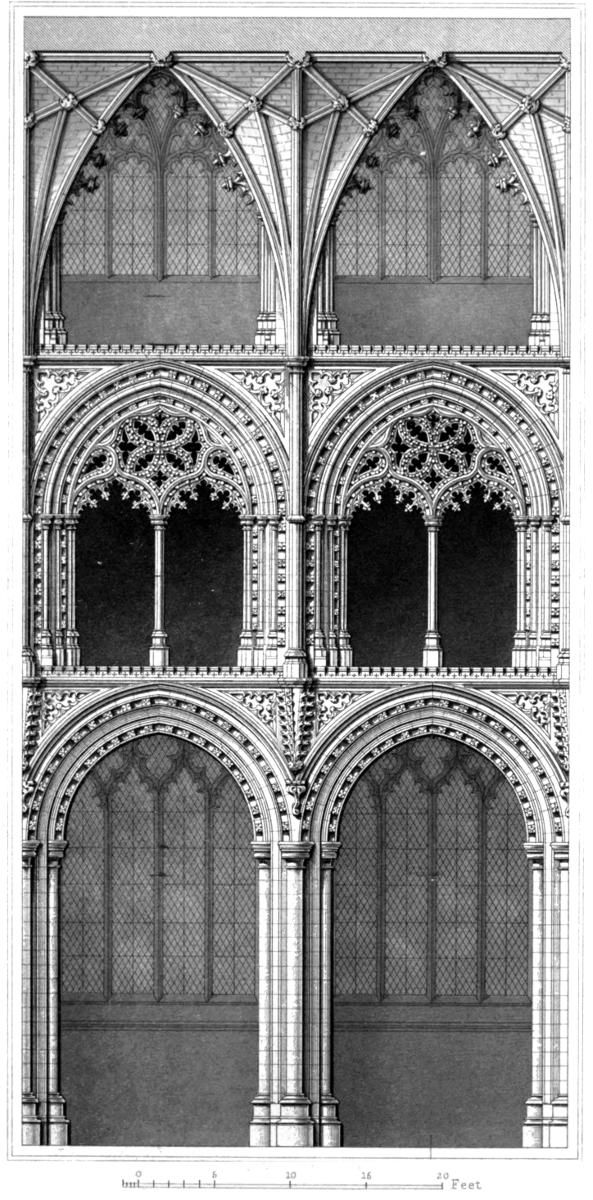

In architecture, Morris and his followers advocated the examples of Gothic church architecture and English vernacular house styles. Europeans, too, looked to their own regional building styles. This preference for homegrown architecture partly explains why the Arts & Crafts style is so varied.

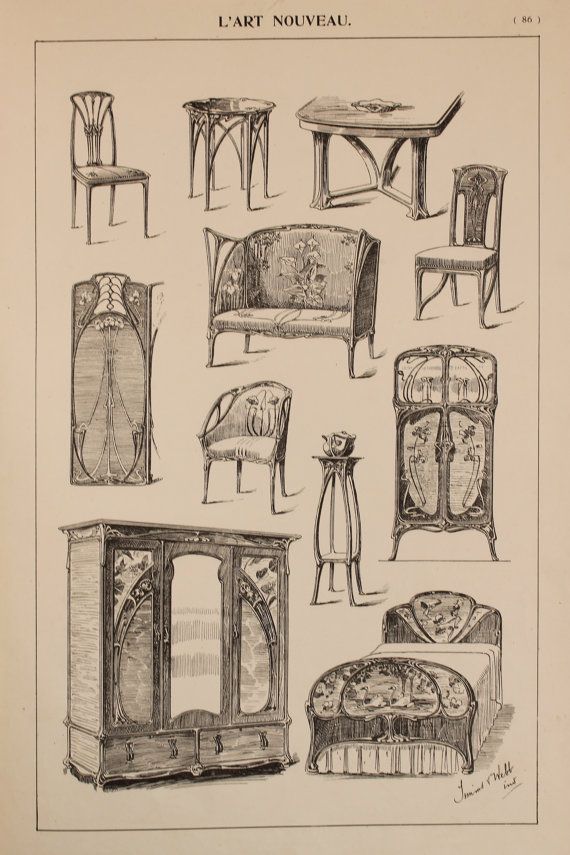

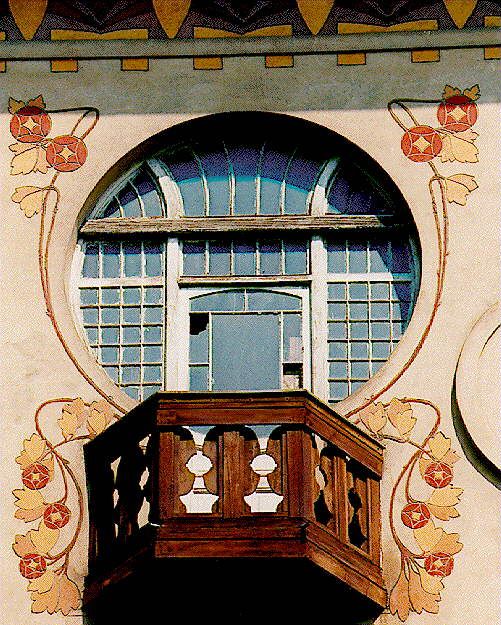

In Europe, the Arts & Crafts movement flourished in several distinctively regional subsets, particularly Austria’s Secession Movement, Germany’s Jugendstil, and France’s Art Nouveau. All turned away from mass production and toward hand craftsmanship for both buildings and objects.

Sidelights flanking the front door were restored to their original configuration. The replacement door is by cabinetmaker Charles Saenger.

The replacement door is by cabinetmaker Charles Saenger.

William Wright

Americans also sought a simpler but aesthetically richer life, and they were enthusiastic about their own diverse architectural heritage. But Americans were not about to give up mass production. On the contrary, they believed factories were as capable as individual craftsmen of producing quality design—and at a much lower cost, making it available to more people.

Among the first to trumpet the value of factory-made objects for American homes was Frank Lloyd Wright, who addressed the topic in 1901 in his famous Chicago lecture, “The Art and Craft of the Machine.” (Wright, it must be said, did not espouse mass-produced objects in houses he himself designed.)

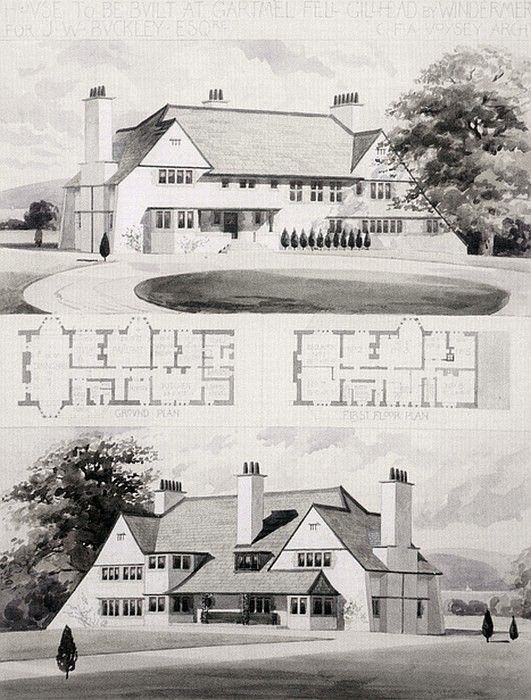

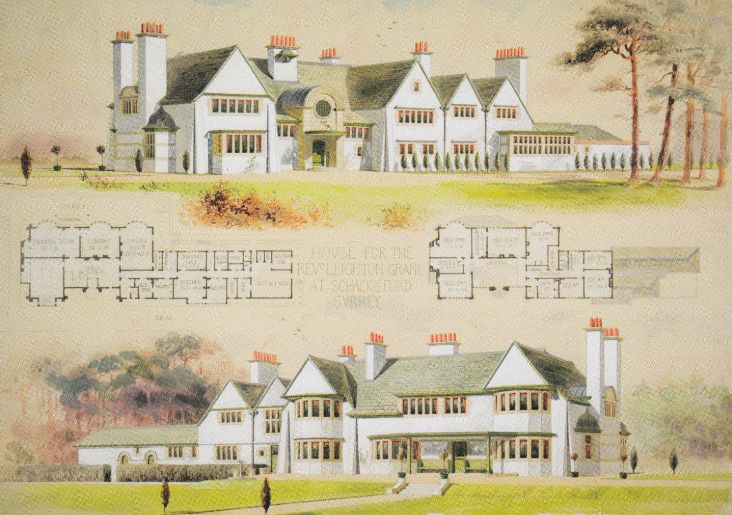

Edward Bok, editor of The Ladies’ Home Journal, the era’s largest and most influential women’s magazine, quickly picked up the Arts & Crafts banner. In 1895, the Journal initiated a long-running series of Arts & Crafts-influenced house designs by noted architects, including William L. Price, E. G. W. Dietrich, and Frank Lloyd Wright. Charmingly restrained room layouts by luminaries such as Will Bradley conveyed Arts & Crafts values to millions of readers.

Price, E. G. W. Dietrich, and Frank Lloyd Wright. Charmingly restrained room layouts by luminaries such as Will Bradley conveyed Arts & Crafts values to millions of readers.

Better lines, better proportions, better trim—and an Arts & Crafts house rises in the neighborhood.

Gridley + Graves

The biggest promoter of the American Arts & Crafts movement, however, was an erstwhile furniture-maker named Gustav Stickley. From 1900 until 1916, Stickley’s hugely popular magazine, The Craftsman, encouraged readers to build, furnish, and decorate their own homes using Arts & Crafts principles. Simple furnishings from the Stickley factories were featured in the magazine’s pages, which also provided free designs for Craftsman houses. This, of course, inspired countless bungalows and Foursquares that still dot the streets of suburbs around the country.

Stickley’s enthusiasm for the bungalow helped the style spread rapidly during the first quarter of the century—so much so that the words “Craftsman” and “bungalow” are now inextricably linked in the old-house lexicon. Stickley was no purist, but he urged the use of handmade decorations, from pottery to silver to textiles—even made by the homeowners themselves.

Stickley was no purist, but he urged the use of handmade decorations, from pottery to silver to textiles—even made by the homeowners themselves.

Handmade Virtues

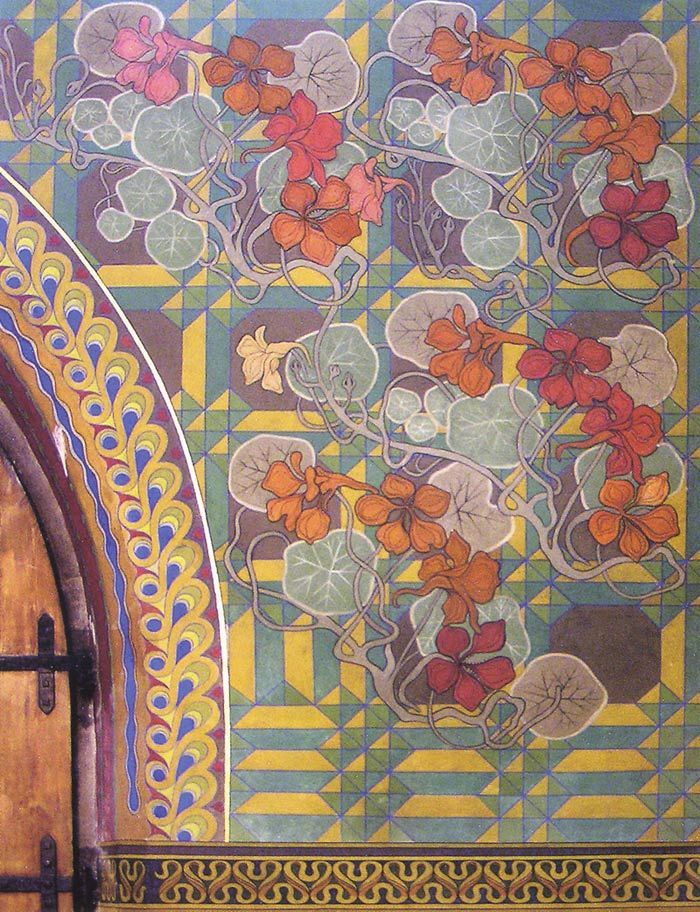

In Kansas City, Missouri, Mineral Hall (built in 1913 by Louis Curtiss), with its ornamented, arched entrance, is probably the best American example of Art Nouveau architectural features, rarely seen in this country.

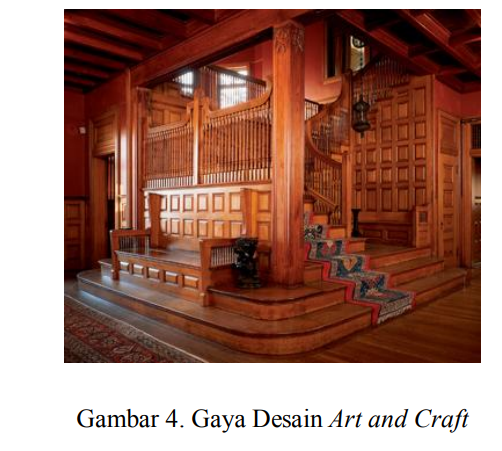

Arts & Crafts architecture was so closely tied to interior design that the furniture and fittings of a house, even more than its external appearance, determine its place in the Arts & Crafts camp. Simple but sophisticated design and exquisite craftsmanship were hallmarks of the movement.

Handmade ceramics—including tiles for both indoor and outdoor use—became a thriving Arts & Crafts industry throughout the country. Rookwood, Pewabic, Batchelder, Van Briggle, and a host of other potteries flourished. Potteries and other Arts & Crafts industries, in fact, provided the first entry for large numbers of women into the world of design.

As in England and Europe, natural building materials such as fine woods, stone, and brick were favored. Americans, however, readily took to newly improved, fireproof concrete building products. Henry Chapman Mercer’s famous Moravian Pottery and Tile Works factory in Doylestown, Pennsylvania, which specialized in glazed tiles in medieval patterns, was constructed entirely of concrete, as was Fonthill, Mercer’s castle-like home nearby.

Architectural Legacy

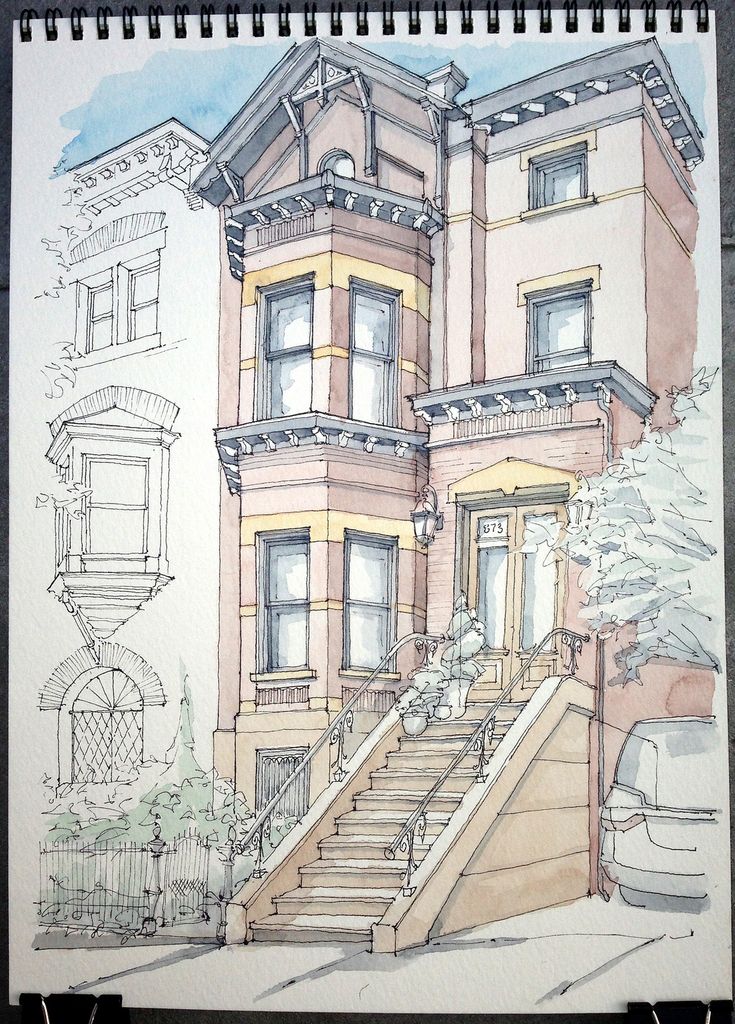

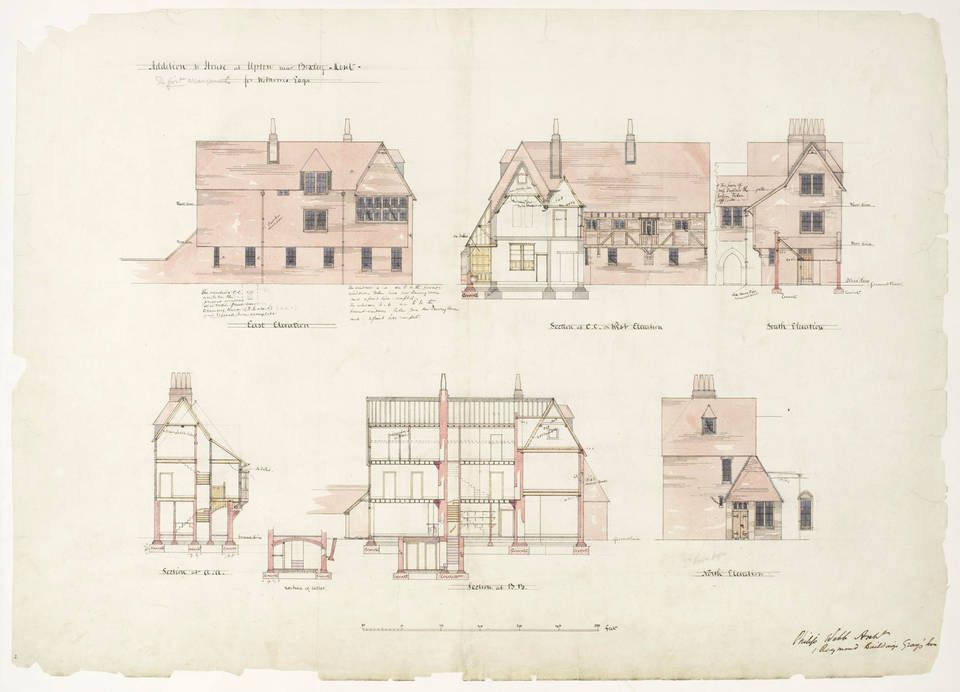

Dozens of architects throughout the United States designed Arts & Crafts houses, drawing on architectural styles traditionally found in the region. In the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic, English styles were generally emphasized for country homes and town houses. Prominent eastern architects included William L. Price, Aymar Embury, Wilson Eyre, and Joy Wheeler Dow.

With a broad terrace on the first floor and a covered porch on the second level, the back of the house is oriented towards the distant ocean view.

Brian Vanden Brink

California was an early hotbed of Arts & Crafts design, led by Pasadena’s Charles and Henry Greene. The Greene’s Gamble House, often called the “ultimate bungalow,” was an Arts & Crafts showplace. It was one of many houses that illustrated the influence of Japanese design on their work, especially the use of wooden construction. A bevy of Bay Area designers put their own twist on shingled wood construction, especially in San Francisco, Oakland, and Berkeley. Among them was Bernard Maybeck, whose shingled houses often showed Gothic references. Julia Morgan, famous as the designer of William Randolph Hearst’s San Simeon, carried out many other Arts & Crafts commissions in California.

The Greene’s Gamble House, often called the “ultimate bungalow,” was an Arts & Crafts showplace. It was one of many houses that illustrated the influence of Japanese design on their work, especially the use of wooden construction. A bevy of Bay Area designers put their own twist on shingled wood construction, especially in San Francisco, Oakland, and Berkeley. Among them was Bernard Maybeck, whose shingled houses often showed Gothic references. Julia Morgan, famous as the designer of William Randolph Hearst’s San Simeon, carried out many other Arts & Crafts commissions in California.

As is typical of Wright’s Prairie School homes, the front entrance here is concealed from the street. Instead, it is the front porch, protected by an expansive, cantilevered roof, which is the highlight of the façade.

Andy Olenick

The Prairie School architects of Chicago—including Purcell and Elmslie, George Maher, Walter Burley Griffin, and Marion Mahoney (only lately given her due as a designer)—developed and spread Frank Lloyd Wright’s message. Henry Trost’s work in El Paso and elsewhere reflected his training as a Prairie School architect, while in Kansas City, Louis Curtiss took a very different approach; his Mineral Hall may be America’s only true Art Nouveau house.

Henry Trost’s work in El Paso and elsewhere reflected his training as a Prairie School architect, while in Kansas City, Louis Curtiss took a very different approach; his Mineral Hall may be America’s only true Art Nouveau house.

In the Southwest, Mary Jane Colter was among a number of women architects contributing to the movement with her distinctive Southwestern-influenced hotels and restaurants along the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad. Even the South had its Arts & Crafts architects, among them Henry J. Klutho of Jacksonville, Florida.

As a movement, Arts & Crafts didn’t survive World War I. Postwar houses most often wore eclectic European revival styles—from Tudor to Spanish to Mediterranean. Nonetheless, by banishing Victorian decorative excess, the Arts & Crafts pushed American architecture decisively toward Modernism and left a rich legacy shared by thousands of old-house owners today.

Tags: arts & crafts bungalow craftsman James C. Massey & Shirley Maxwell OHJ July/August 2008 Old-House Journal stickley william morris

What Is an Arts and Crafts Home?

By

Ashley Knierim

Ashley Knierim

Ashley Knierim is a home decor expert and product reviewer of home products for The Spruce. Her design education began at a young age. She has over 10 years of writing and editing experience, formerly holding editorial positions at Time and AOL.

Her design education began at a young age. She has over 10 years of writing and editing experience, formerly holding editorial positions at Time and AOL.

Learn more about The Spruce's Editorial Process

Updated on 02/02/22

Fact checked by

Sarah Scott

Fact checked by Sarah Scott

Sarah Scott is a fact-checker and researcher who has worked in the custom home building industry in sales, marketing, and design.

Learn more about The Spruce's Editorial Process

Arts and Crafts-style homes may be one of the most complex styles of architecture. While there are many key features of an Arts and Crafts home, the style draws similarities from several other architectural aesthetics, making it a little more difficult to pick it out. In older homes. you'll find that Arts and Crafts isn't exactly a single style, but rather a specific approach to many different types of architecture.

The History of Arts and Crafts Homes

As a reaction to the manufactured and ornate styles of the Victorian age, Arts and Crafts-style homes embraced handcrafted design and approachable materials. The style originated in England in the mid-19th century and came to America around the beginning of the 20th century. The term "Arts and Crafts" refers to a broader social movement that encompasses not just architecture, but also interior design, textiles, fine art, and more.

The style originated in England in the mid-19th century and came to America around the beginning of the 20th century. The term "Arts and Crafts" refers to a broader social movement that encompasses not just architecture, but also interior design, textiles, fine art, and more.

The design movement began as a revolt against the opulence of the Industrial Revolution, where design could be needlessly overdone. Arts and Crafts instead focused on the opposite–instead of mass-produced and uninspired, the movement was all about being handcrafted and personal. The idea was that if quality could replace quantity, good design and good taste would prevail.

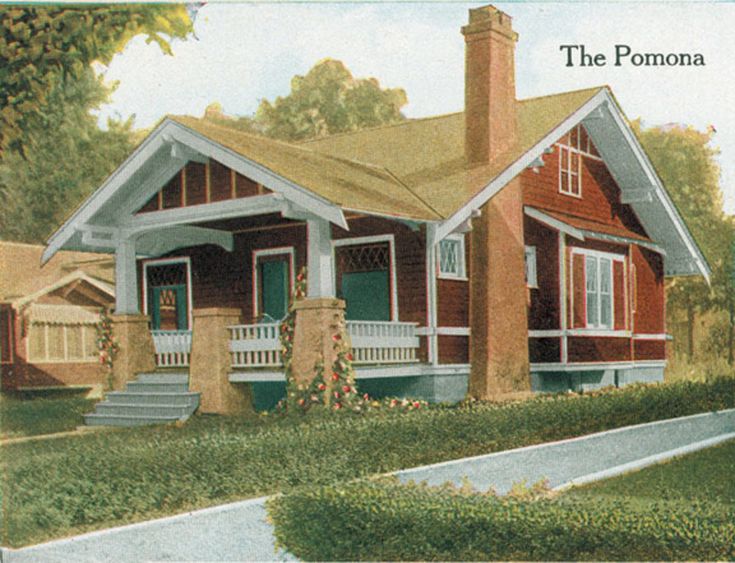

The Arts and Crafts movement was directly tied to the rise of Craftsman and Bungalow-style homes, architecture that played off of the same mentality of simple but thoughtful structures. Bungalows were intended to give working-class families the ability to own a well-designed home that was easy to maintain and manage.

bungalowsandcottages / Instagram

What Defines an Arts and Crafts Home?

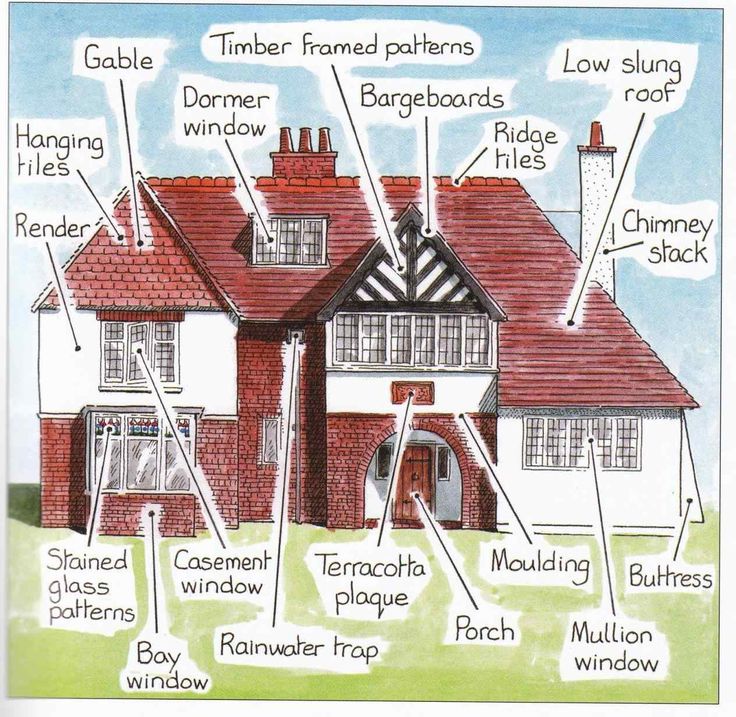

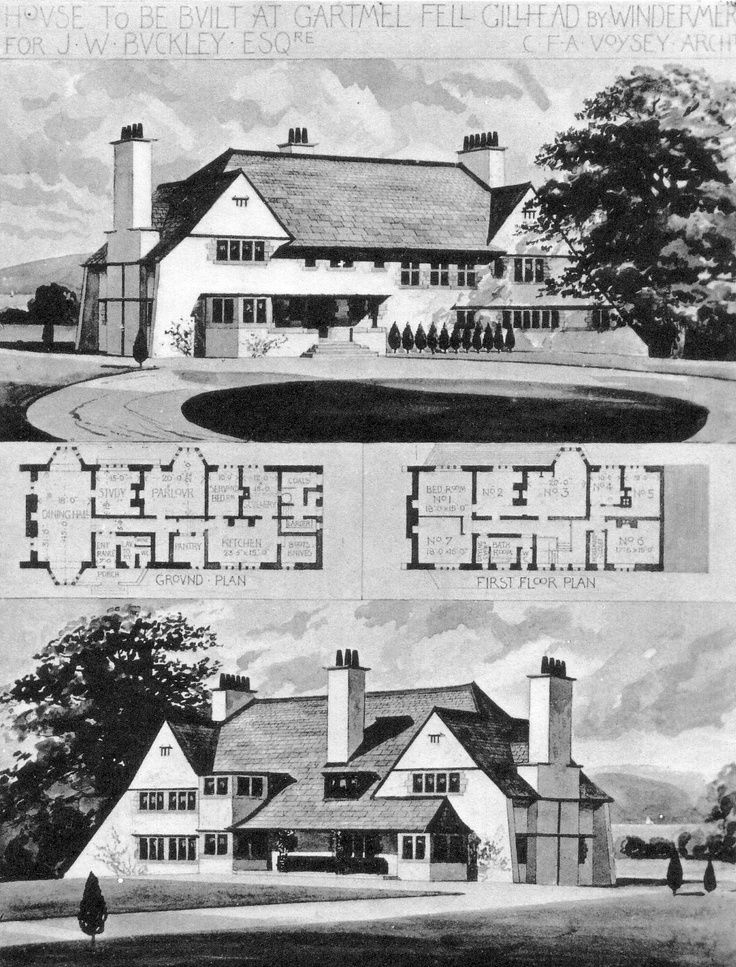

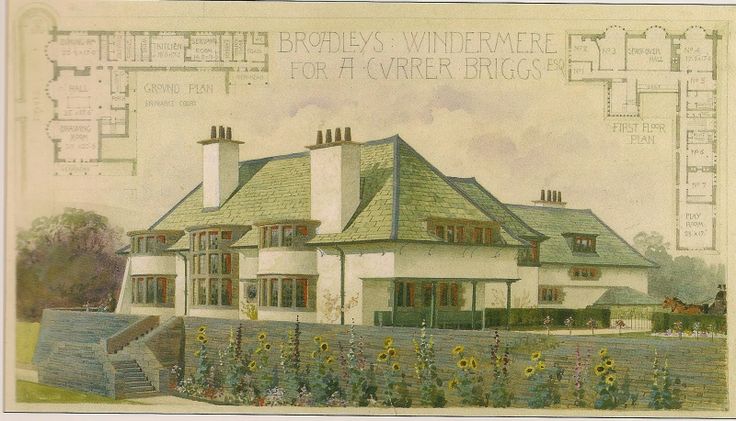

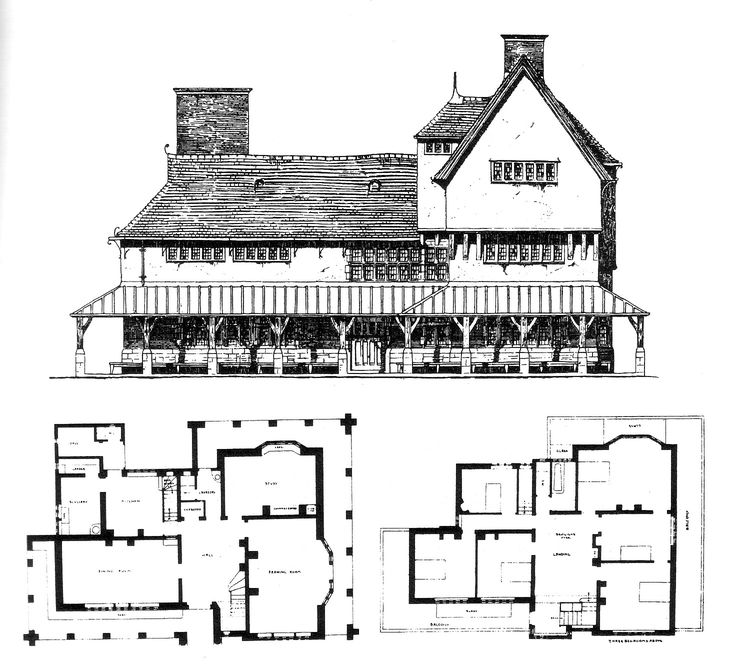

An Arts and Crafts-style home can be symmetrical or asymmetrical in its facade and is typically low to the ground. They are designed to use space efficiently and economically, and by nature require little upkeep if planned well. They often feature multiple chimneys and a very prominent "sheltering roof." Windows are plentiful, but often made up of small panes.

They are designed to use space efficiently and economically, and by nature require little upkeep if planned well. They often feature multiple chimneys and a very prominent "sheltering roof." Windows are plentiful, but often made up of small panes.

There are many types of architecture within the Arts and Crafts style, including Craftsman and Bungalows.

Key Elements

When looking at an Arts and Crafts home, you will find a few key elements that transcend across styles.

Roof: The roof of an Arts and Crafts home is typically low pitched, with wide, unenclosed eave overhangs.

Exposed beams: The rafters on the roof and the beams inside the home are often exposed in an Arts and Crafts home.

Built-ins: One key element of this design style is the rise of built-in furniture. The movement brought a wave of built-in bookshelves, window seats, and cabinets that felt custom to the house and perfectly suited to the design.

Windows: The home's windows are typically made up of smaller panes and set in multiple assemblies.

Fireplace: An Arts and Crafts home often had a very large fireplace that centered the open living space and acted as a focal point for the room.

Prominent Porches: It's rare to find an Arts and Crafts-style home without an obvious porch equipped with prominent columns. The porch is typically limited to the front door area, but sometimes will wrap around the house.

Floor Plan: The homes of the Arts and Crafts movement featured wide-open floor plans, a stark contrast to the boxy, segmented rooms of the Victorian-style homes that came before.

Common Materials

Again, in an effort to reject the design periods that came before, Arts and Crafts homes were made from natural elements. The use of local materials was encouraged, and you will often see the use of real stone, brick, and wood throughout the home.

You'll also find fine handiwork features throughout the home, such as hammered metalwork and the use of authentic copper and bronze. Designers and craftsmen took pride in their work, and so an Arts and Crafts home will often feel well-made and thoughtful.

Interesting Facts

The Arts and Crafts-style home is one that inspired and directly led to many of the houses you'll spot across America today. Because the design is that of handcrafted simplicity, these homes rarely go out of style, even as design trends change throughout the years.

Though Arts and Crafts design became less popular after World War I, the ideals behind the movement (well-made, handcrafted design) remained important throughout history. You'll still find examples of Arts and Crafts-style homes and the cozy Bungalow or the Craftsman home.

Arts and Crafts and Architecture - Studopedia

Theoretical part of the course

"Fundamentals of the Theory of Arts and Crafts with Practicum"

Problems of synthesis. Theory (from the Greek theoria - consideration, research), a system of basic ideas in a particular branch of knowledge; a form of knowledge that gives a holistic view of the patterns and essential connections of reality. Theory as a form of research and as a way of thinking exists only in the presence of practice. Activity (DOING) is what distinguishes arts and crafts from other arts. Thus, it forms the foundations of decorativeness in art, in which fine art is not reduced to the obligatory nature of drawing, but art is more in line with the problem of representation, that is, the presence of imagery. A smooth, carefully planed board in the hands of a skilled carpenter will remain a product of craftsmanship. The same board in the hands of an artist, not even planed, with burrs and splinters, under certain conditions, can become a fact of art. DPI involves the awareness of the value of a thing in the process of making it. The theory of the foundations of arts and crafts leads to the practice of this art, its decorative essence.

Theory (from the Greek theoria - consideration, research), a system of basic ideas in a particular branch of knowledge; a form of knowledge that gives a holistic view of the patterns and essential connections of reality. Theory as a form of research and as a way of thinking exists only in the presence of practice. Activity (DOING) is what distinguishes arts and crafts from other arts. Thus, it forms the foundations of decorativeness in art, in which fine art is not reduced to the obligatory nature of drawing, but art is more in line with the problem of representation, that is, the presence of imagery. A smooth, carefully planed board in the hands of a skilled carpenter will remain a product of craftsmanship. The same board in the hands of an artist, not even planed, with burrs and splinters, under certain conditions, can become a fact of art. DPI involves the awareness of the value of a thing in the process of making it. The theory of the foundations of arts and crafts leads to the practice of this art, its decorative essence. Decorativeness as a property is manifested in any object, phenomenon, quality, technology. The DPI itself is decorative in nature. On the one hand, these are creations of pictures of life, on the other hand, they are the decoration of this life. nine0003

Decorativeness as a property is manifested in any object, phenomenon, quality, technology. The DPI itself is decorative in nature. On the one hand, these are creations of pictures of life, on the other hand, they are the decoration of this life. nine0003

Decorativeness is determined by the features and knowledge of the subject. Decore (fr.) - decoration. The concept of decorativeness of an object is determined by the artistic features of a thing, the artistic practice of its creation. Decoration is an activity aimed at transforming a figurative motif into an objective motif. At the center of this process is the artistic thing as a category of completeness. A thing is considered as a value, an artistic thing as an exceptional value. There is a figure of the master, artist and author. DPI does things and endows it with applied meanings. The applied properties of DPI form the tasks of its practice. In practice, DPI is directly dependent on materials and technologies, and appears in absolute freedom of representation. nine0003

nine0003

DPI has deeply and firmly penetrated into our lives, it is constantly near and accompanies us everywhere and is inseparable from our life. DPI connects with all spheres of human life, and becomes an integral part of ourselves. The concept of "synthesis" in this case synthesizes the entire human nature of life as a single whole in the aggregate "artistic". Having considered the concept of "synthesis" (Greek "synthesis" - connection, fusion) and the concept of "decorativeness" (French "decor" - decoration) in a semantic connection, we can conclude that DPI can be in contact with any type of human activity. DPI is found everywhere: in design, technology, sculpture, industry, architecture, etc. This is its peculiarity and uniqueness. nine0003

The synthetic nature of the decorative arts. The concept of decorativeness should be considered as something mythological, that is, a certain phenomenon of a decorative property. Everything is decorative, depending on the point of view. Any object as an unidentified object appears before us as a mystery of synthesis. Art only explains, it itself cannot be explained. The problem of synthesis is the problem of identifying artistic value. The synthetic nature of decorativeness is inherent in any work of art. In painting (fine art), a picture is painted with paints (oil, acrylic), on a canvas of a certain configuration, is framed, placed in space and produces a decorative effect on the emotional state of the living environment. In music, a melody is written with signs on paper, performed by an orchestra under the direction of a conductor in a certain space of a certain room. In this process, everything is aesthetically defined: from the shape of the musical notation, the graceful shape of the violin, to the conductor's baton and the musician's uniform. In literature, the text is written pen on paper , typed on the keyboard, printed in the printing house in the form of a book and placed on a bookcase shelf spine out.

Any object as an unidentified object appears before us as a mystery of synthesis. Art only explains, it itself cannot be explained. The problem of synthesis is the problem of identifying artistic value. The synthetic nature of decorativeness is inherent in any work of art. In painting (fine art), a picture is painted with paints (oil, acrylic), on a canvas of a certain configuration, is framed, placed in space and produces a decorative effect on the emotional state of the living environment. In music, a melody is written with signs on paper, performed by an orchestra under the direction of a conductor in a certain space of a certain room. In this process, everything is aesthetically defined: from the shape of the musical notation, the graceful shape of the violin, to the conductor's baton and the musician's uniform. In literature, the text is written pen on paper , typed on the keyboard, printed in the printing house in the form of a book and placed on a bookcase shelf spine out. And here everything is aesthetically determined: from the stroke of the pen to the captal of the book block. The artistry of literature turns into the figurativeness of book graphics, into the spirituality of the interior. The art of the theater is thoroughly illuminated by decorativeness as an artistic argument for a theatrical performance. The problems of synthesis as an artistic phenomenon, the synthetic nature of decorative art, are most consistently embodied in the art of cinema. In the practice of cinema, the synthetic nature of the decorative manifests itself as a total process of synthesis of all types of art. nine0003

And here everything is aesthetically determined: from the stroke of the pen to the captal of the book block. The artistry of literature turns into the figurativeness of book graphics, into the spirituality of the interior. The art of the theater is thoroughly illuminated by decorativeness as an artistic argument for a theatrical performance. The problems of synthesis as an artistic phenomenon, the synthetic nature of decorative art, are most consistently embodied in the art of cinema. In the practice of cinema, the synthetic nature of the decorative manifests itself as a total process of synthesis of all types of art. nine0003

From decorative to synthesis. Synthesis is an artistic task, an applied task of connecting the author's intention in real space with the context of the environment, which is embodied, as a rule, in time. This choice is determined by the responsibility for the consequences of education. Responsibility is motivated by the living conditions in which the synthesis is produced. Art is directed to man. The aesthetic transformation of a given context in reality most often alienates the practice of mandatory transformations from purely artistic tasks. Example: in building a house, the main thing is warmth, comfort, and not its aesthetic appearance. Its aesthetic properties are manifested at the genetic level (host - hostess). If an object with aesthetic functions is being built (a cultural institution, cinemas, a circus, a theater), the result is an alienation of the aesthetic quality of the design from the real problems of construction (materials, technologies - cost). The alienation of the concrete and the real, the alienation of the aesthetic motive, the artistic transformation from the environment, is the result of the absence of the problem of synthesis. Architecture is the most striking example of the manifestation of synthesis in art. Synthesis (Greek - connection, merging) - is perceived as a procedure, assumption, intention, in which the presence of a temporary factor in real practice is perceived as a complete object, the artistic value of a thing.

Art is directed to man. The aesthetic transformation of a given context in reality most often alienates the practice of mandatory transformations from purely artistic tasks. Example: in building a house, the main thing is warmth, comfort, and not its aesthetic appearance. Its aesthetic properties are manifested at the genetic level (host - hostess). If an object with aesthetic functions is being built (a cultural institution, cinemas, a circus, a theater), the result is an alienation of the aesthetic quality of the design from the real problems of construction (materials, technologies - cost). The alienation of the concrete and the real, the alienation of the aesthetic motive, the artistic transformation from the environment, is the result of the absence of the problem of synthesis. Architecture is the most striking example of the manifestation of synthesis in art. Synthesis (Greek - connection, merging) - is perceived as a procedure, assumption, intention, in which the presence of a temporary factor in real practice is perceived as a complete object, the artistic value of a thing. Synthetic - something artificial, intangible, multidimensional. The synthesized thing assumes the integrity of the artistic component: target, functional (technological), natural, landscape, geographical, linguistic, costly, etc.

Synthetic - something artificial, intangible, multidimensional. The synthesized thing assumes the integrity of the artistic component: target, functional (technological), natural, landscape, geographical, linguistic, costly, etc.

Who determines the tasks of synthesis? In a situation of "synthesis" a conglomerate of conflict arises between the customer (authority, entrepreneur, owner), the executor of the will of the customer (architect, designer, artist). Who directly embodies the idea (foreman, technologist, builder) and who directly finances the synthesis enterprise. Inevitably there is a problem of clarification of authorship. Who is a synthesizer? Customer, architect (designer), artist? Historical experience shows that the least effective and fraught with stagnation is the protective and restrictive path of ideological interference in matters of purely professional affiliation. And monumental art, because of the power of influence and general accessibility, however, like any art, should be free from this qualification. But the ideal has been proclaimed here, and as long as the state and money exist, there will be ideology and order - monumental art is directly dependent on them. nine0003

But the ideal has been proclaimed here, and as long as the state and money exist, there will be ideology and order - monumental art is directly dependent on them. nine0003

Synthesis involves creativity as a moment of individual, dictatorial and collective co-creation, but with the priority of the creator responsible for the result (Boriska - the bell-caster from A. Tarkovsky's film "Andrei Rublev").

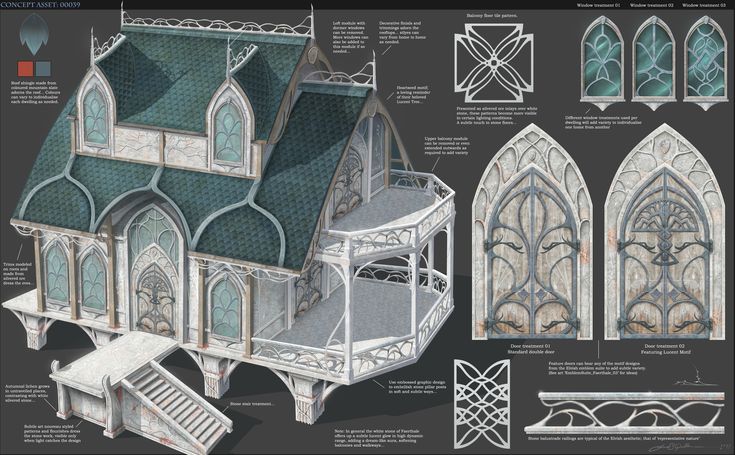

Synthesis embodies the artistic process of organic combination of material co-procedures of compositional unity of styles in one place with a uniform quality of materials and technologies. Producers of DPI are actively involved and fill the space, organizing the synthesis. The artist follows the synthesis of decorative products and architecture. The tasks of the DPI are determined by the will of the synthesizer - (architect, designer, artist). The embodiment of the synthesis of architectural space assumes that the artist takes into account all the circumstances that determine the figurative characteristics, his material, technological and other qualities, taking into account the nature of his style and the formative features of space, based on his own and personal preferences within his professional priorities. No dictate of design is an obstacle to the manifestation of the synthetic form of DPI. This nature is actively manifested and synthesized. The old DPI technology is being embodied, improved and a new one is emerging. DPI organizes the architectural space directly through the aesthetic, artistic design of the structure of this space (wall, floor, windows, doors, etc.), taking into account and on the basis of its own genres and technologies that arose initially and are actively developing independently. The perfection of synthesis is expressed by the penetration of the aesthetic into the artistic: panels, artistic painting of surfaces, stained glass, parquet, decoration of window openings, doorways, interior details, household items, utensils, utilitarian devices, communication links of the environment. nine0003

No dictate of design is an obstacle to the manifestation of the synthetic form of DPI. This nature is actively manifested and synthesized. The old DPI technology is being embodied, improved and a new one is emerging. DPI organizes the architectural space directly through the aesthetic, artistic design of the structure of this space (wall, floor, windows, doors, etc.), taking into account and on the basis of its own genres and technologies that arose initially and are actively developing independently. The perfection of synthesis is expressed by the penetration of the aesthetic into the artistic: panels, artistic painting of surfaces, stained glass, parquet, decoration of window openings, doorways, interior details, household items, utensils, utilitarian devices, communication links of the environment. nine0003

There is a human factor in the organization of synthesis. The role of a DPI participant can be reduced to one local model range. And in the future, the human factor itself forms from these participants what it seems necessary to it. The architect takes on the role of the artist, in turn the artist takes on the responsibility of the architect. The lower the synthetic level of complexity of practical tasks, the higher the bar for the influence of the human factor becomes. Each participant in this process considers it possible for himself, to the extent of his understanding, to take part in it and, one way or another, influence its final appearance. nine0003

The architect takes on the role of the artist, in turn the artist takes on the responsibility of the architect. The lower the synthetic level of complexity of practical tasks, the higher the bar for the influence of the human factor becomes. Each participant in this process considers it possible for himself, to the extent of his understanding, to take part in it and, one way or another, influence its final appearance. nine0003

2. FROM SYNTHESIS TO MONUMENTAL ART

The ideas of the synthesis of DPI and architecture were most fully embodied in monumental art.

Monumental art (lat. monumentum , from moneo - I remind you ) is one of the plastic, spatial, fine and non-fine arts. This kind of them includes works of large format, created in accordance with the architectural or natural environment, compositional unity and interaction with which they themselves acquire ideological and figurative completeness, and communicate the same to the environment. Works of monumental art are created by masters of different creative professions and in different techniques. Monumental art includes monuments and memorial sculptural compositions, paintings and mosaic panels, decorative decoration of buildings, stained-glass windows, as well as works made in other techniques, including many new technological formations (some researchers also refer works of architecture to monumental art). nine0003

Works of monumental art are created by masters of different creative professions and in different techniques. Monumental art includes monuments and memorial sculptural compositions, paintings and mosaic panels, decorative decoration of buildings, stained-glass windows, as well as works made in other techniques, including many new technological formations (some researchers also refer works of architecture to monumental art). nine0003

Synthesis as an artistic task and as an applied practice of architecture and fine arts has always existed since the need for it arose. Monumental art is a concrete form of embodiment of synthesis, the art of proportion, large-scale art. It contains unconditional design motivations for creative action, attitudes towards proportionality with a person, forms and visual effects of visual, psychological impact and perception. In monumentality there are ideas of theater. Perceptions of reality in a special reality, decorative conventions, emotional pathos. The image of the space on which the scene-action is played out is like in a theater. nine0003

nine0003

In the 20th century, monumental art is interpreted as the idea of cinema. Projection distance of a thing. The goal is to exalt and perpetuate. Monumental art develops its own rules for making a work, its own genres and canons. The creation of space, the idea of spatial (synthetic) art permeates it through and through. Detail disappears, details disappear. The scale and proportion of all parts of the whole triumph. A monumentalist, like a film director, must be excellently prepared in all areas of creativity, since he makes a work-thing, the embodiment of the synthesis of all arts. nine0003

Synthesis became fashionable in the 1960s. The mechanism for implementing the ideas of synthesis in the practice of architecture was the so-called monumental and decorative art. The ideas of DPI in it penetrate into the synthesis as the ideas of fashion. Monumental art - the idea of decoration, decorative dress, fashionable clothes for architecture. At present, in monumental art, the concepts of modern (avant-garde), contemporary art are being established, based on the fact of the scale of the masses and the spectacular perception, psychological adherents of the spatial and semantic projections of the monumental form. The penetrating property of the projection of the meaning of the concept as an actual image in the context of the organized environment becomes a synthesizing factor. nine0003

The penetrating property of the projection of the meaning of the concept as an actual image in the context of the organized environment becomes a synthesizing factor. nine0003

Aesthetics and artistic style formed by the synthesis of . The problem of style and aesthetics of synthesis is the problem of artistic taste in general in art and of a single person. Style in this case is a fact of manifestation of individual preferences and the level of artistic skill. The aesthetics of synthesis can be dictated by the taste of the customer or consumer. Style as an idea of expressing aesthetics becomes the general line of the embodiment of synthesis, becomes its main task. Synthesis generates style, style produces synthesis. Monumentality in art history, aesthetics and philosophy generally refers to that property of an artistic image, which, in its characteristics, is related to the category of “sublime”. The dictionary of Vladimir Dahl gives such a definition to the word monumental - "glorious, famous, abiding in the form of a monument. " Works endowed with features of monumentality are distinguished by an ideological, socially significant or political content, embodied in a large-scale, expressive majestic (or majestic) plastic form. Monumentality is present in various types and genres of fine art, but its qualities are considered indispensable for works of monumental art proper, in which it is the substratum of artistry, the dominant psychological impact on the viewer. At the same time, one should not equate the concept of monumentality with the works of monumental art themselves, since not everything created within the nominal limits of this type of representation and decorativeness has features and qualities of genuine monumentality. An example of this is the sculptures, compositions and structures created at different times, which have the features of gigantomania, but do not carry the charge of true monumentalism and even imaginary pathos. It happens that hypertrophy, the discrepancy between their sizes and meaningful tasks, for one reason or another, makes us perceive such objects in a comic way.

" Works endowed with features of monumentality are distinguished by an ideological, socially significant or political content, embodied in a large-scale, expressive majestic (or majestic) plastic form. Monumentality is present in various types and genres of fine art, but its qualities are considered indispensable for works of monumental art proper, in which it is the substratum of artistry, the dominant psychological impact on the viewer. At the same time, one should not equate the concept of monumentality with the works of monumental art themselves, since not everything created within the nominal limits of this type of representation and decorativeness has features and qualities of genuine monumentality. An example of this is the sculptures, compositions and structures created at different times, which have the features of gigantomania, but do not carry the charge of true monumentalism and even imaginary pathos. It happens that hypertrophy, the discrepancy between their sizes and meaningful tasks, for one reason or another, makes us perceive such objects in a comic way. From which we can conclude: the format of the work is far from the only determining factor in the correspondence between the impact of a monumental work and the tasks of its internal expressiveness. The history of art has enough examples when craftsmanship and plastic integrity make it possible to achieve impressive effects, power of impact and drama only due to compositional features, consonance of forms and transmitted thoughts, ideas in works of far from the largest sizes (“Citizens of Calais” by Auguste Rodin slightly exceed nature ). Often, the lack of monumentality informs the works of aesthetic inconsistency, the lack of true correspondence to ideals and public interests, when these creations are perceived as nothing more than pompous and devoid of artistic merit. Works of monumental art, entering the synthesis of with architecture and landscape, become an important plastic or semantic dominant of the ensemble and the area. Figurative and thematic elements of facades and interiors, monuments or spatial compositions are traditionally dedicated, or with their stylistic features reflect modern ideological trends and social trends, embody philosophical concepts.

From which we can conclude: the format of the work is far from the only determining factor in the correspondence between the impact of a monumental work and the tasks of its internal expressiveness. The history of art has enough examples when craftsmanship and plastic integrity make it possible to achieve impressive effects, power of impact and drama only due to compositional features, consonance of forms and transmitted thoughts, ideas in works of far from the largest sizes (“Citizens of Calais” by Auguste Rodin slightly exceed nature ). Often, the lack of monumentality informs the works of aesthetic inconsistency, the lack of true correspondence to ideals and public interests, when these creations are perceived as nothing more than pompous and devoid of artistic merit. Works of monumental art, entering the synthesis of with architecture and landscape, become an important plastic or semantic dominant of the ensemble and the area. Figurative and thematic elements of facades and interiors, monuments or spatial compositions are traditionally dedicated, or with their stylistic features reflect modern ideological trends and social trends, embody philosophical concepts. Usually works of monumental art are intended to perpetuate prominent figures, significant historical events, but their themes and stylistic orientation are directly related to the general social climate and the atmosphere prevailing in public life. Like natural, living, synthetic nature also never stands still. The old is replaced by the new or incorporated into it. Painting develops as graphics, graphics as sculpture. All forms and technologies of art interact in each other, are actively transformed and mixed. Synthetic nature is transformed into a synthetic (monumental) style. nine0003

Usually works of monumental art are intended to perpetuate prominent figures, significant historical events, but their themes and stylistic orientation are directly related to the general social climate and the atmosphere prevailing in public life. Like natural, living, synthetic nature also never stands still. The old is replaced by the new or incorporated into it. Painting develops as graphics, graphics as sculpture. All forms and technologies of art interact in each other, are actively transformed and mixed. Synthetic nature is transformed into a synthetic (monumental) style. nine0003

8. Architecture. Decorative and applied art. History of world and national culture: lecture notes

8. Architecture. Decorative and applied art. History of world and national culture: lecture notesWikiReading

History of world and national culture: lecture notes

Konstantinova S V

Contents

8. Architecture. Arts and Crafts

Architecture. Arts and Crafts

Already in the II millennium BC. e. Jade and bone carving was developed. Green jade was a cult object in China, it was revered as an "eternal stone" that keeps the memory of ancestors. The value of jade was so great that it played the role of gold and silver - coins were made from it, the purity of golden sand was estimated from it. Jade products are mainly produced in Beijing and Shanghai. Ivory carving is developed in Beijing, Guangzhou and Shanghai. The most important center for the production of products using cloisonne enamel is Beijing. Embroiderers usually know dozens of techniques that allow them to subtly convey the texture of an object, the transitions and shades of colors, the volume of the depicted object, as well as spatial perspective. nine0003

The architecture of China is interesting and unusual. Already in the 1st millennium BC. e. the Chinese built buildings of 2–3 or more floors with a multi-tiered roof. Typical was a building consisting of supports in the form of wooden pillars with a tiled roof, which had raised edges and a clearly marked cornice - a pagoda. This type of building was the main one in China for many centuries.

This type of building was the main one in China for many centuries.

In the III century. BC e. more than 700 imperial palaces were built in China. The central hall of one of them accommodated more than 10,000 people. nine0003

The time when a single centralized state was formed in the country (221-207 BC) was marked by the construction of the main part of the Great Wall of China, which has partially survived to this day. It is known that it was built by more than 2 million prisoners, many of whom were punished for dissent. The length of the wall is more than 4 thousand km.

This text is an introductory fragment.

nine0083 3.8. Scythian crafts and applied arts 3.8. Scythian crafts and applied arts Until recently, the concept of "Scythian art" was reduced to gold jewelry from Scythian barrows. The glitter of gold overshadowed the eyes ... Gradually, however, it became clear that the Scythians made not only jewelry. In the depths of

The glitter of gold overshadowed the eyes ... Gradually, however, it became clear that the Scythians made not only jewelry. In the depths of

§ 5. Applied arts

§ 5. Applied art In the XIV century. various branches of applied art are reviving and gaining strength. This is the decoration of dwellings (huts, towers) with wooden carvings, painting of pottery, making salaries for handwritten books, miniatures for their texts, etc. True, much is not0003

Arts and Crafts

applied arts The development of the state, the growth of the well-being of the court aristocracy required the production of an increasing number of luxury items. In this regard, a powerful impetus was given to the development of applied art. Technological excellence achieved

Chinese arts and crafts

Chinese arts and crafts China is rightly called the "silk kingdom". The history of Chinese silk has more than 5 thousand years. For the first time here they began to make magnificent products from the threads secreted by the silkworm larva to create a cocoon, to embroider

The history of Chinese silk has more than 5 thousand years. For the first time here they began to make magnificent products from the threads secreted by the silkworm larva to create a cocoon, to embroider

7. Arts and crafts

7. Arts and crafts Outstanding development in Rus' in pre-Mongolian times received artistic craft. Craftsmen of more than 100 specialties worked in Russian cities. Jewelry art reached an exceptional flourishing. Great Demand Worldwide

5. Arts and crafts

nine0002 5. Arts and crafts The growth of cities and urban settlements, the development of handicrafts contributed to the further development in the 16th century. arts and crafts, the main center of which was Moscow. The best artisans united in royal and metropolitan7. Applied arts

7. Applied art In the 17th century the flowering of applied art, which began in the previous century, continued, the main center of which was the workshops of the Moscow Kremlin (the Armory, Gold, Silver, Tsaritsyna and other chambers). Collected from all over 9 worked in them0003

Applied art In the 17th century the flowering of applied art, which began in the previous century, continued, the main center of which was the workshops of the Moscow Kremlin (the Armory, Gold, Silver, Tsaritsyna and other chambers). Collected from all over 9 worked in them0003

§ 5. Applied arts

§ 5. Applied art In the XIV century. various branches of applied art are reviving and gaining strength. This is the decoration of dwellings (huts, towers) with wooden carvings, painting of pottery, making salaries for handwritten books, miniatures for their texts, etc. True, much is not

Topic 21 Art of Republican Rome (sculpture, painting, arts and crafts)

Topic 21 Fine Arts of Republican Rome (sculpture, painting, arts and crafts) The era of the republic in Rome (the end of the 6th century BC - the last third of the 1st century BC) and the features of the development of culture and art in this era (slow development in

6.

Architecture, sculpture. Arts and Crafts

Architecture, sculpture. Arts and Crafts 6. Architecture, sculpture. Arts and Crafts In Japan since the 5th century. built Buddhist temples. Open for viewing, they served as a decoration of the area; their high multi-tiered roofs organically fit into the relief, harmoniously blending with the surrounding

Topic 15 Architecture and fine arts of the Old and Middle Babylonian periods. Architecture and fine arts of Syria, Phenicia, Palestine in the II millennium BC. e

Topic 15 Architecture and fine arts of the Old and Middle Babylonian periods. Architecture and fine arts of Syria, Phenicia, Palestine in the II millennium BC. uh Chronological framework of the Old and Middle Babylonian periods, the rise of Babylon at

Topic 16 Architecture and fine arts of the Hittites and Hurrians. Architecture and art of Northern Mesopotamia at the end of II - beginning of I millennium BC.

e

e Topic 16 Architecture and visual arts of the Hittites and Hurrians. Architecture and art of Northern Mesopotamia at the end of II - beginning of I millennium BC. uh Features of Hittite architecture, types of structures, construction equipment. Hatussa architecture and issues

Topic 19 Architecture and fine arts of Persia in the 1st millennium BC AD: Architecture and Art of Achaemenid Iran (559-330 BC)

Topic 19 Architecture and fine arts of Persia in the 1st millennium BC AD: architecture and art of Achaemenid Iran (559-330 BC) General characteristics of the political and economic situation in Iran in the 1st millennium BC. e., the rise to power of Cyrus from the Achaemenid dynasty in

3. ARCHITECTURE, PAINTING, APPLIED ARTS

3. ARCHITECTURE, PAINTING, APPLIED ART Architecture.