How to display china in a hutch

20+ Creative Ideas for Displaying China

Every item on this page was curated by an ELLE Decor editor. We may earn commission on some of the items you choose to buy.

Make elegant plates and serving vessels an integral element of your decor.

By Alyssa Gautieri | Chairish

Stacy Bass

When you have beautiful formal dishware, you want to show it off. Elegant plates and serving vessels become an integral element of the decor—if styled correctly—whether hung on the wall in full view of the dining table or relegated to a china hutch in the kitchen. See how expert design professionals created beautiful spaces to display their clients' curated china and ceramics collections.

Michael J Lee Photography

1 of 24

Clean & Sophisticated

Kathy Marshall Design uses green-blue cabinetry with glass doors and brass fixtures to display white, ceramic dishware.

Helen Norman

2 of 24

Satisfying Symmetry

Bright, white dishes are symmetrically hung on the wall in this elegant dining room by Kathryn Ivey Interiors.

Keith Scott Morton

3 of 24

Timeless Design

There is a long history behind the use of blue and white china, and the classic color combination is often reinvented in modern-day spaces. Design by Deborah Leamann Interior Design.

Bjorn Wallander

4 of 24

Vintage Charm

Here, D'Aquino Monaco uses vintage elements—from the dining room chairs, to the porcelain collection hanging from the walls.

Eric Roth Photography

5 of 24

A Vibrant Display

Arrange dishware along a wallpapered wall as Gerald Pomeroy Interiors does in this vibrant space.

Julie Soefer

6 of 24

Antique Meets Modern

This modern dining room by Laura U boasts an antique china hutch that has been refinished with a blue stain.

Carter Berg

7 of 24

Artsy & Antique

This antique server functions as a display for colorful ceramics. Design by Liliane Hart Interiors.

Design by Liliane Hart Interiors.

David W. Gilbert

8 of 24

Classic Color

Reminiscent of an older time, this vintage space by Blythe Home is completed with a display of blue and white china.

Werner Straube

9 of 24

Bright & Bold

Displayed in bright blue cabinetry, dishware becomes the focal point of this butler's pantry by Amy Kartheiser Design.

Rett Peek

10 of 24

All About the Antiques

Antique platters and majolica are showcased above a refurbished table that was once a bench. Design by Goddard Design Group.

Max Kim-Bee

11 of 24

Decorate with Dishes

A dining hutch is more than a place to store dishware, it's often used as a central design element—like in this space by Brockschmidt & Coleman.

David Bader

12 of 24

A Pop of Color

Bright and colorful dishes shine through the glass display of this gray cabinetry. Design by Wade Weissmann Architecture.

Simon Brown

13 of 24

Stylish Shelving

Here, Beata Heuman uses a display of framed artwork and ceramic dishes to complement the kitchen's curved walls and marble backsplash.

Tim Street Porter

14 of 24

A Touch of Modern

Incorporate stainless steel cabinetry for a sleek and modern touch. Breakfast area by Tim Barber.

Neil Rashba

15 of 24

Coastal Chic

Coastal-style cabinetry displays a collection of elegant china. Design by Amanda Webster Design.

Thomas Kuoh

16 of 24

Soothing Grays

This sophisticated butler's pantry by Nest Design Company uses gray cabinetry for a collection of neutral-colored dishware.

Stacy Bass

17 of 24

Mix & Match

Here, Sarah Blank Design Studio displays a variety of dishware in a farmhouse-style kitchen.

Werner Straube

18 of 24

All White

Amy Kartheiser Design shows off white ceramics in bright, modern cabinetry.

David Livingston

19 of 24

Inspired by the Victorian Era

This baby blue dining room by Suzanne Childress Design blends modern elements with Victorian-era design.

Susan Gilmore Photography

20 of 24

Eye-Catching Cabinetry

A china cabinet creates intrigue in a space by Murphy & Co. Design.

Design.

Alexander Bailhache, courtesy of Veranda Magazine

21 of 24

Along the Walls

Placed intentionally along the walls, these white dishes are various shapes and sizes. Design by Charles Spada Interiors.

Buff Strickland

22 of 24

Sophisticated Style

Although dishware is often associated with vintage or rustic spaces, Annie Downing Interiors uses a sophisticated corner hutch in this contemporary dining room.

Carter Berg

23 of 24

Simple Elegance

Functional dishware can be stylish too. Here, Liliane Hart Interiors displays everyday dishware using glass cabinet doors.

Andrew McKinney

24 of 24

An Assortment of China

Here, Tres McKinney Design uses two different cabinets for a variety of china and ceramic dishware.

23 Dining Rooms with Floral Wallpaper

Alyssa Gautieri | Chairish Alyssa Gautieri is an editor for Chairish who explores a range of interior design and architecture trends — from unique artwork and furnishings, to intriguing exteriors and outdoor living areas.

Tips and Tricks For Styling Your China Cabinet

By Casey Watkins | Published on

Buy Now

You’re brave for clicking on this post! Most of the time, china cabinets come with visions of Grandma’s dining room and rose speckled china and shepherdess figurines. That alone can make you shy away from a china cabinet of your own. But you have to admit, they are very practical pieces of furniture. If you have a set of dishes for special occasions, it’s a good idea to have a place to show them off. Thankfully there are a few tricks that will make your china cabinet into your favorite dining room piece. Here are 20 tips and tricks for styling your china cabinet.

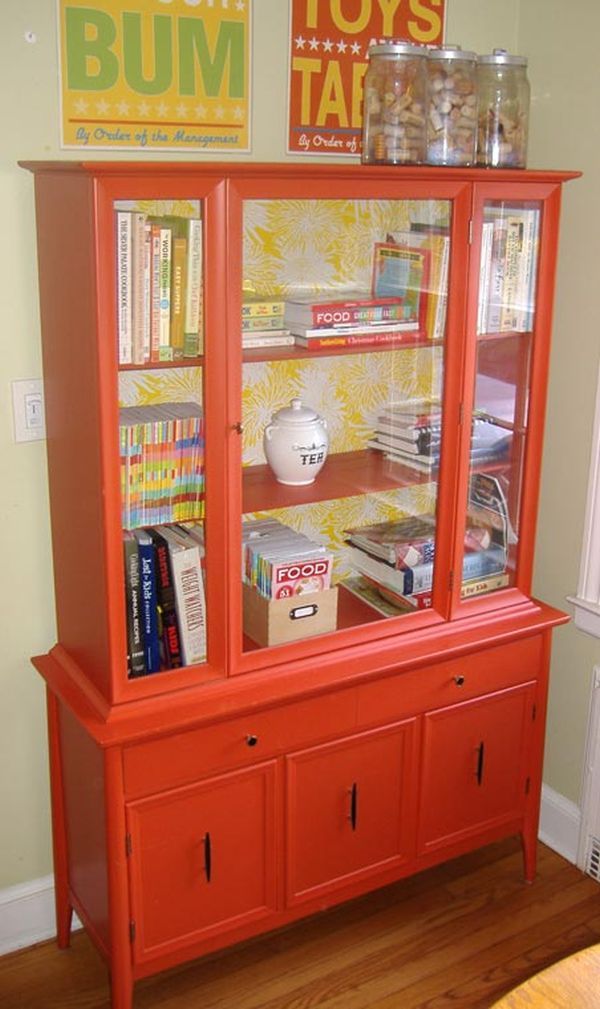

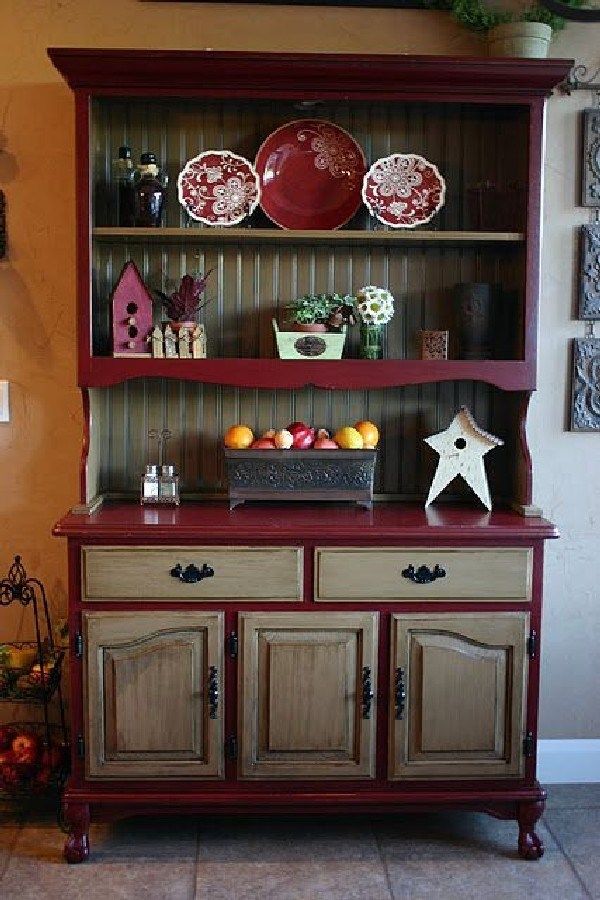

1. A Bright Coat Of Paint

View in gallery

Who says china cabinets have to be wood and mirrors? Paint yours a bright contrasting color that will make anyone who walks into the room green with jealousy. (via Dimples and Tangles)

(via Dimples and Tangles)

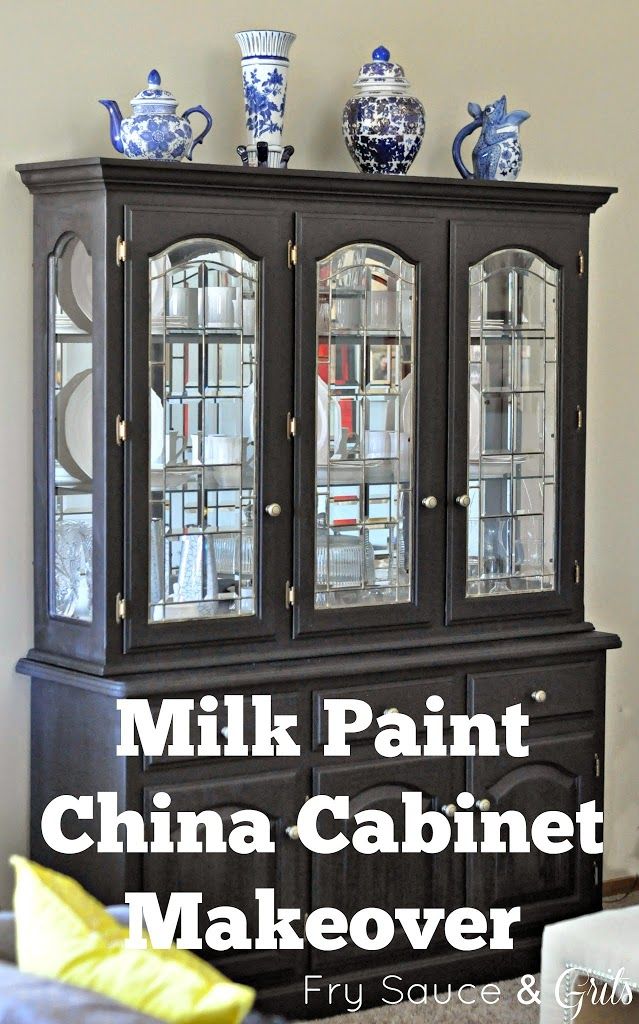

2. Add A Patterned Background

View in gallery

Sometimes the best background is a patterned background. Use fabric or paper to cover the back of your china cabinet and you’ll give all your trinkets inside an instant makeover too. (via Primitive and Proper)

3. Or Paint A Plain Background

View in gallery

Is pattern too busy on the eyes in your subtle home? Just paint the inside of your china cabinet a color complementary to the outside. It will help give some depth and interest without being a distraction. (via Confessions of a Serial DIYer)

4. Replace The Glass With Wire

View in gallery

For the majorly rustic homes, you’ll want to replace the glass doors on your china cabinet with chicken wire. Even unpainted, it makes quite an art piece all by itself. (via Cedar Hill Farmhouse)

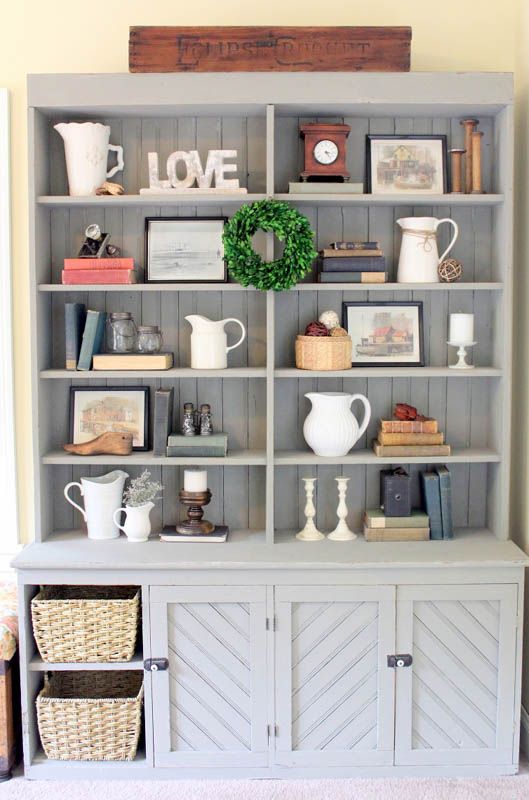

5. Go For A Rustic Style

View in gallery

I just love the look of all white dishes. It’s so clean and simple. This look is especially appropriate for country styled homes and French styling and rustic styling. All you need is a rough would dining table to finish the look. (via Grand Design Co)

This look is especially appropriate for country styled homes and French styling and rustic styling. All you need is a rough would dining table to finish the look. (via Grand Design Co)

6. Purchase Patterned Dishes

View in gallery

If all white is too bland and plain for you, no one said you couldn’t have patterns galore. Pick some colors that will match with your home’s color scheme and then snatch up all the patterned dishes you can find. (via Domaine)

7. Place Touches Of Silver And Gold

View in gallery

No matter what else you put in your china cabinet, metallics are a must. The glint of silver and gold will bring your dishes up to date and will make things look a little more modern for your dining room. (via Jersey Ice Cream Company)

8. Decorate For The Holidays

View in gallery

Don’t forget to decorate! As you’re changing up your mantle and bookcases with the seasons and holidays, make sure you include your china cabinet. A well placed pumpkin or a bowl of ornaments can do wonders. (via French Country Cottage)

(via French Country Cottage)

9. Don’t Be Afraid To Stack Your Dishes

View in gallery

We’ve established that the real purpose of a china cabinet is storage. So don’t be disappointed if that’s all you can use it for. Go ahead and stack your dishes and stash your bowls. As long as the things you put in there are worth keeping, they’ll create a china cabinet worth looking at. (via Carrie Bradshaw Lied)

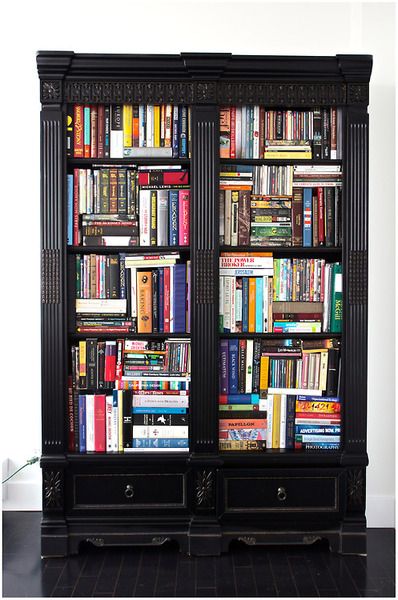

10. Use Your China Cabinet For Other Things

View in gallery

Did you know that china cabinets aren’t only for dining rooms? Use one in your living room in place of a bookshelf. Or stack your linens inside to create a linen cupboard. Put one in your bedroom to hold frames and sentimental trinkets in style. With all the purposes a china cabinet can fill, there is no reason for you to skip it. (via Pencil Shavings Studio)

11. Place Things On Top of Your China Cabinet

View in gallery

Sometimes people feel as if they can only put their items inside their china cabinet, bypassing a large amount of storage space there is on top! You absolutely can put larger cooking items here, like a crockpot or fondue pot, or you can decorate it as you see fit. This idea does work best if the top of your china cabinet is flat, but if you do have one that has different levels, you can still make this work like they did in Round Décor, by placing non-breakable decorations on each level.

This idea does work best if the top of your china cabinet is flat, but if you do have one that has different levels, you can still make this work like they did in Round Décor, by placing non-breakable decorations on each level.

12. Replace The Background With Mirrors

View in gallery

For those who have an especially small home, it can help to install a mirror as the background of your china cabinet. Not only will this make the cabinet itself seem bigger, but it will make it look as if it takes up less space as well! You can see this idea in action on BSC Insider to see if it might work for your home. Granted, it will require regular cleaning, but the sleek look it will bring to your dining room is worth it!

13. Leave Your China Cabinet Mostly Empty

View in gallery

Have you been gifted a china cabinet but don’t have any china to put into it? A china cabinet can be a beautiful decoration piece, even its just left mostly empty! Check out this china cabinet on Timeless Creations. There are only three items placed in the cabinet, and two on top, but they are placed in a way that brings a natural, almost outdoors, feel into the room, while the owner of this cabinet still has a place to store coffee cups! This idea is especially ideal when you are renting a place that comes with a china cabinet but don’t have any items to use it for.

There are only three items placed in the cabinet, and two on top, but they are placed in a way that brings a natural, almost outdoors, feel into the room, while the owner of this cabinet still has a place to store coffee cups! This idea is especially ideal when you are renting a place that comes with a china cabinet but don’t have any items to use it for.

14. Group Items In Your Cabinet

View in gallery

When you have a large variety of dishes that all need to be stashed in your china cabinet, it can be difficult to know how to organize them in a way that still looks great. And honestly, the best thing you can do is just group things together! This will give your china cabinet a flowy and sophisticated look, as well as make it easy for you to find items when you need them. I Should Be Mopping The Floor has a great example of this, and we especially love how a bucket of flowers was used to fill empty space on one shelf.

15. Build Your China Cabinet Into The Wall

View in gallery

This next styling tip will only work when are in the middle of remodeling your home, but if you are, then consider building your china cabinet into the wall. This will give you more space, as you won’t have a cumbersome cabinet taking up space while still being able to store all the dishes you need. You can find this idea on Driven by Décor and use it to transform the look of the china cabinet in your home!

This will give you more space, as you won’t have a cumbersome cabinet taking up space while still being able to store all the dishes you need. You can find this idea on Driven by Décor and use it to transform the look of the china cabinet in your home!

16. Remove The Doors Completely

View in gallery

Installing open shelving can be a very easy way to upgrade a kitchen and modernize it without having to do a lot of renovation, and the same goes for your china cabinet. If you have an older china cabinet with glass, or a door style that you don’t think matches your décor, then get rid of them completely. You’ll want to remove the hinges as well, and fill the holes left behind, but after a fresh coat of paint you could have an amazing open style china cabinet.

17. Use Plants For Decor

View in gallery

Plants are an amazing decorating tool, and there’s no reason that you can’t use them in your china cabinet as well! Even if the china cabinet in your home doesn’t get much sun, you can still use silk plants to spruce up the look and balance of your cabinet. In this china cabinet styled by Making it in The Mountains, two green silk plants were strategically placed in an all-white cabinet. This gives the cabinet a farmhouse look without having to change the cabinet or the dishes.

In this china cabinet styled by Making it in The Mountains, two green silk plants were strategically placed in an all-white cabinet. This gives the cabinet a farmhouse look without having to change the cabinet or the dishes.

18. Place Heavy Items On The Bottom

View in gallery

When you step back and take a look at your china cabinet, does it look unbalanced? This could simply be because of your item placement. Try arranging it so that your largest and heaviest items are on the bottom shelf, and your smaller items are on the top shelves like they did in Pender And Peony. This will make it look more even and less top heavy while also making it easier to access those heavier items without having to reach up to the top shelf.

19. Stand Your Plates Upright

View in gallery

People often associate standing the plates up in your china cabinet as an old-fashioned decoration idea, but this isn’t true at all! Standing up a few plates in your china cabinet can draw attention to it, as well as let you know where stacks of certain dishes are located. This doesn’t mean you need to line your entire cabinet with dishes on end, but take a look at this china cabinet on Domestic Charm, where 3 different plates were put on their ends to create balance and style for this china cabinet.

This doesn’t mean you need to line your entire cabinet with dishes on end, but take a look at this china cabinet on Domestic Charm, where 3 different plates were put on their ends to create balance and style for this china cabinet.

20. Use Beverages As Decoration

View in gallery

Everyone knows that even when you may seem to have the biggest kitchen, finding places to store things food and beverages can be tough. Did you know that you can actually store sodas and other beverages in your china cabinet? Just line them up nicely with the labels facing out like they did in this example in Alice Lane Home Collection, and they will have your china cabinet looking great! It is suggested you create this look with nice looking glass bottle sodas but arranged and stacked soda cans could look neat as well.

Still think china cabinets are just for the elderly? Hopefully, this article has shown you several ways you can transform that dreaded hand me down china cabinet into a beautiful decoration and storage space for your home. And whether you end up using the cabinet for china, or something completely different, like books, you will love the way your china cabinet looks so much so that you may just forget that you used to think they weren’t part of a modern home!

And whether you end up using the cabinet for china, or something completely different, like books, you will love the way your china cabinet looks so much so that you may just forget that you used to think they weren’t part of a modern home!

From the history of Japanese porcelain

Pottery on the islands of the Japanese archipelago originated in the Neolithic (the oldest products date back to the tenth millennium BC). But the production of porcelain began only in the 17th century. According to legend, in 1610, a native of Korea Ri San Pei (李参平) at the foot of Mount Izumi-yama (泉山磁) on the island of Kyushu in Arita (有田) discovered kaolin deposits and founded the first workshop for the production of porcelain. Soon, hundreds of pottery workshops appeared in the neighborhood, named after the owner - Hirado (平戸), Mikawachi (三川内), Kakiemon (酒井田) and others.

In the sixty years since the founding of the first workshop, more than two million pieces of porcelain have been produced in Arita. To a large extent, this was facilitated by the revival of trade during the formation of the Tokugawa dynasty - both within the country and with merchant ships of the East India Companies.

To a large extent, this was facilitated by the revival of trade during the formation of the Tokugawa dynasty - both within the country and with merchant ships of the East India Companies.

in the photo: "Arrival of the Portuguese ship", Japanese screen, 1620-1640.

The particular interest of European merchants in Japanese porcelain was due to the fact that in the first half of the 17th century, East India companies actively exported products from the Chinese workshops of Jingdezhen. However, due to the economic decline at the end of the Ming dynasty, which resulted in a civil war, work there was completely stopped. The enterprising Dutch established a trade office in Nagasaki (displacing the Portuguese and achieving a monopoly on trade) and replaced Chinese porcelain with Japanese.

European orders not only stimulated the rapid development of production, but also set a certain format for manufactured products. And if the early works of Japanese potters imitated Korean porcelain, products of Dehua and Jingdezhen, then in the 18th-19th centuries they were greatly influenced by European tastes.

As a result, by the middle of the 19th century, several styles had formed in Japanese porcelain art, each of which inscribed its chapter in the history of world artistic practice.

ARITA (有田) / IMARI (伊万里)

Arita is the collective name for porcelain made in more than 1,000 pottery kilns in the Arita District (an urban area in Saga Prefecture, Kyushu). The craftsmen brought their products for sale to the nearby port city of Imari (伊万里). Therefore, everything produced in the Arita region is often called by the name of this (one of the few open to foreign ships) center of trade - Imari.

Pictured: Arita wares, 17th century

Works from the 17th-18th centuries were made in the techniques sometsuke (染付, blue and white porcelain painted with cobalt-based paste over which glaze was applied) and iroe (色絵, multi-colored porcelain, painted over glaze with reddish-red, yellow, green, turquoise and purple enamels).

in the photo: Arita products, XVII century

KAKIemon (柿右衛門様式)

The style is named after the pottery dynasty founded by Sakaida Kakiemon (酒井田 柿右衛門) in Arita in the early 17th century. According to legend, the name "Kakiemon" was received by the master Sakaida from the shogun for the enamel formula of the rich shade of ripe persimmon (柿, "kaki" - persimmon). Since then, persimmon has been a kind of hallmark of the dynasty. Subsequently, the soft red, yellow, blue and turquoise green that are strongly associated with this style, as well as an asymmetrical pattern that leaves a large blank space on a white field covered with a layer of translucent glaze, complemented the palette of Kakiemon shades.

in the photo: products of the Kakiemon workshop, Edo period

Images of flowers, birds and magical animals only emphasized the exquisite charm of nigoside (milky white). In addition, along the edge on Kakiemon products, there is often a colored rim, uncharacteristic for other Arita workshops, as well as relief decorations.

in the photo: products of the Kakiemon workshop, late 17th century

Porcelain from the Kakiemon workshops first came to Europe at the end of the 17th century. Among its owners were the Queen of England Mary II, the Polish King Augustus the Strong and other crowned persons.

in the photo: products of the Kakiemon workshop, late 17th - early 18th centuries

The Kakiemon style made such a strong impression on Europeans that they began to copy it in the English workshops of Chelsea and Worcester, in the "cradle of European porcelain" - the Meissen factory in Saxony and the French manufacture of Chantilly.

in the photo: samples of products of European workshops in the Kakiemon style, from left to right - a coffee pair (Meissen factory, XVIII century), paired vases (Chantilly factory, XVIII century), a box (Meissen factory, XVIII century) .

This style flourished at the end of the 17th - beginning of the 18th centuries, however, due to the high complexity, the production of nigoshide fell into decline and was fully revived only in the middle of the 20th century. Today, the custodian of the 400-year-old brand tradition is a fifteenth-generation descendant of Sakaida Kakiemon.

Today, the custodian of the 400-year-old brand tradition is a fifteenth-generation descendant of Sakaida Kakiemon.

HAKUJI (白磁)

Hakuji white porcelain, also geographically belonging to the Arita region, was oriented to Chinese Dehua white porcelain as its prototype, but over time it developed and became a completely independent direction of decorative art in Japan . Hakuji production reached its peak during the Meiji era (1868-1

in the photo: Nabeshima porcelain of the 17th-18th centuries

Unlike most other stoves in Arita, the Japanese tradition can be traced in the design of products from the very beginning - fabric ornaments, free use of empty space, flower-bird ornament , abstract patterns. The "signature" dishes with the image of jugs are especially original. The shape of the products imitated Japanese lacquerware, which was preferred by the aristocrats of the Edo period. Until the beginning of the Meiji era, products from Nabeshima kilns were practically not exported.

in the photo: Nabeshima porcelain of the 17th-18th centuries porcelain stone was found in the gold mines of Kutani (九谷, literally "Nine Valleys", currently the city of Kaga, Ishikawa Prefecture, Honshu Island). The head of the Maeda clan, Maeda Toshiharu, who controlled these lands, sent his entourage, Goto Saijiro, to Arita to learn the art of making porcelain. Upon his return, Goto Saijiro founded a pottery center in Kutani, where he began to produce porcelain for the Maeda clan. Morikage Kusumi, the official painter of the Maeda clan, a famous artist of the Kano school, also took part in the work on the design of products.

pictured: Ko-Kutani porcelain, circa 1700.

Art historians today refer to objects made in the next few decades as Ko-Kutani (古九谷, old Kutani). Ko-Kutani are subdivided into Aote (青手), covered with bright enamels of dark blue, rich green, purple and yellow hues, and Iroe (色絵), combining red, purple, green, dark blue and yellow colors. In the ornament, images of plants, birds and landscapes complemented abstract patterns. To protect objects from wear and tear, they were covered with transparent glazes over the enamel.

In the ornament, images of plants, birds and landscapes complemented abstract patterns. To protect objects from wear and tear, they were covered with transparent glazes over the enamel.

photo: Ko-Kutani porcelain, early 18th century.

By 1730, the production of Kutani porcelain had ceased and resumed only 80 years later. The new time has made its own adjustments both in technology and in the design of products, which today are commonly called Saiko-Kutani (再興九谷, literally: “reborn Kutani”).

At the beginning of the 19th century. in the Nine Valleys region, several stoves appeared, each with its own owner and style.

Mokubei (木米)

In 1807, the owner of the Kasugayama Kilns (Kanazawa District) in Daishoji invited Aoki Mokubei (木米, 1767-1833), a prominent potter and artist of the time, from Kyoto to revive the porcelain industry. A student of Okuda Eisen (the first porcelain maker in Kyoto), Aoki already had his own workshop and a unique creative style. Much in his work indicates the strong influence of masterpieces of Chinese art, rethought in a very original and bold way.

Much in his work indicates the strong influence of masterpieces of Chinese art, rethought in a very original and bold way.

Designed in Daishoji under the direction of Aoki, figures of people, plants and fantastic animals are depicted on a solid red background. In honor of its creator, this style is now called Kutani-Mokubei.

Pictured: Aoki Mokubei porcelain, early 19th century.

Yoshidaya (吉田屋)

The design of the products copied the early style of Ko-Kutani: flowers, birds and traditional ornaments were depicted on a green, yellow, purple or blue background, as well as an ornament in the form of dots. The red color was never used.

in the photo: Yoshidai porcelain, 1920s.

Iidaya (飯田屋)

In 1831, the Yoshidai kilns in Daishoji changed hands and became the property of Miyamoto-ya Uemon (宮本山宇右衛門). The artist Iidaya Hachiro-emon (飯田屋八郎右衛門) became the ideological inspirer and "art director" of the workshop. For the next 20 years, Miyamoto's kilns produced aka-e porcelain (赤絵, literally: "red paintings"), painted with fine and delicate red enamels and gilding. The design was dominated by a variety of floral and geometric ornaments. This style is today named after its creator Hachirode (八郎手, "Hachiro's hand").

For the next 20 years, Miyamoto's kilns produced aka-e porcelain (赤絵, literally: "red paintings"), painted with fine and delicate red enamels and gilding. The design was dominated by a variety of floral and geometric ornaments. This style is today named after its creator Hachirode (八郎手, "Hachiro's hand").

Pictured: Hachirode porcelain, 1930s.

Eiraku (永楽)

Beginning in 1865, the famous Kyoto artist Eiraku Wazen (永楽和全, 1823-1896) headed the Miyamoto-ya workshops. He develops the aka-e style of his predecessor, solemn and flamboyant gold arabesque painting over red enamel, sometimes combining it with blue and white somatsuke and polychrome aote.

in the photo: Eiraku porcelain, 1960s.

Shoza (庄三)

Kutani porcelain is world famous due to master Shoza (1816-1883). Shodza's work absorbed the experience of his predecessors and raised the Kutani brand to an unprecedented height. Having founded his business in 1841 in Terai (Ishikawa Prefecture), this master was the first to use aniline dyes, which made it possible to expand the color palette and achieve softer color transitions. On top of a complex, finely traced, multi-colored pattern, he decorated his products with gilding kinran-de (金襴手, literally: "golden brocade"). This style was later called "saishiki kinrande".

Having founded his business in 1841 in Terai (Ishikawa Prefecture), this master was the first to use aniline dyes, which made it possible to expand the color palette and achieve softer color transitions. On top of a complex, finely traced, multi-colored pattern, he decorated his products with gilding kinran-de (金襴手, literally: "golden brocade"). This style was later called "saishiki kinrande".

Pictured: Shouza porcelain, mid-19th century.

Shoza's workshop produced many excellent artists whose work dates back to the beginning of the reign of Emperor Meiji, an era marked by Japan's renunciation of self-isolation and the opening of borders for cultural and commercial ties with the West. It was during this period that Japanese porcelain officially participates in international trade exhibitions, where it receives the highest marks.

photo: Shoza porcelain, mid-19th century.

After the success at the Vienna exhibition in 1873, production began to gain even more momentum, European orders stimulated the opening of more and more furnaces in Kaga.

Saiji (細字)

The founder of the style is Oda Seizan (小田清山), who decorated the surfaces of cups, goblets, incense burners and vases with poetic lines at the beginning of the Meiji era. In 2005, the art of Saiji miniature calligraphy was declared a cultural heritage of Ishikawa Prefecture. The guardian of the tradition today is the great-grandson of the master, Tamura Casey (田村敬星).

In the photo: miniature calligraphy Siji, modern works

In the twentieth century to technological techniques that have already become the classic of Kutani, new:

Aotibu (青粒, “blue grains”) ornament) blue dots filling the space between the golden lines.

Yuri Kinsai (釉裏金彩, glaze over gold) - a transparent glaze is applied over silver or gold inlay (powder or thin foil). Products in this style are distinguished by a special radiance and solemnity. In addition, the glaze protects the metal from external factors and abrasion.

Hanazume (花詰, flower pattern) the entire surface of the product is covered with a flower pattern made in the five-color Kutani palette and gilding.

Sai-yu (彩釉), a decoration method in which the glaze seems to “flow”, forming soft transitions of shades.

Kutani marking

Only from the beginning of the 19th century. Kutani products begin to be labelled. Seals could be of two types: an overglaze mark in the form of the hieroglyph "fuku" (福, "happiness") in archaic writing in a square cartouche or the toponym "Kutani" (九谷), applied with underglaze paint or imprinted in the ceramic mass on the bottom of the item. Sometimes the name of the workshop or the name of the master was added to the toponym.

In 1975, the Kutani style was declared a national intangible heritage at the state level. Today there are several hundred workshops producing porcelain in this style.

SATSUMA (薩摩)

Satsuma is the historical name of a province in the territory of present-day Kagoshima Prefecture in the south of Kyushu Island, famous for the production of porcelain.

Until the 16th century, traditional Japanese pottery was produced in the Satsuma-yaki (薩摩焼) kilns in Kyushu. But after the shogun Toyotomi Hideyoshi brought 80 ceramists from a military campaign to North Korea, among other "trophies", the production of original Japanese porcelain began to be accelerated, including in Kyushu, where deposits were discovered near the village of Seigawa, Ibushiki county porcelain stone. Local clay, after firing, turned into high-class, thin-walled, white porcelain. Therefore, Satsuma-style wares can be divided into two fundamentally different categories: the original, dark Ko-satsuma (古薩摩) ceramics of the early period and the exquisitely decorated, thin-walled Kyo-satsuma (京薩摩) porcelain from Kyoto, intended for export, of the late period.

The oldest examples of early Ko-satsuma date from the Genroku period (1688-1704). All of them have a dark shard with a high iron content and are covered with dark glaze. Raised relief, prints and clay carvings were used as decor. Until the end of the 18th century, Satsuma kilns produced products aimed at the domestic market: utensils for everyday use and utensils for the tea ceremony.

Pictured: Ko-Satsuma

Kyo-Satsuma (京薩摩)

Satsuma porcelain flourished at the Kyoto pottery workshops, Kyo-yaki (京焼). Since the 8th century, Kyoto (京, Kyo for short) has been the capital of Japan, the political and cultural center of the country, and a concentration of art crafts, including traditional Japanese ceramics. But not porcelain: until the end of the 18th century, porcelain was not produced in Kyoto. The main reason for this was the rejection of his masters of the tea ceremony. Their adherence to the philosophy of Zen and the aesthetic of wabi-sabi was at odds with the lavish decorativeness of porcelain, which they felt was at odds with the Japanese artistic tradition.

Only in the Edo period, when the tea ceremony became an integral part of city life and sencha tea became fashionable, did big changes occur in the organization of the tea event. The turning point was associated with the work of such famous Japanese artists as Okuda Eisen (奥田 穎川, 1753-1811), who was the first to work with porcelain, as well as his students and followers - Aoki Mokubei (青木木米, 1767–1833), Eiraku Hozana ( 1795–1854), Nin'ami Dohati (1783–1855).

The famous Awata-yaki (粟田焼), Mizoro-yaki (御菩薩焼) and Kiyomizu-yaki (清水焼) kilns began to experiment with porcelain along with traditional ceramics.

Pictured: early porcelain from the Awata-yaki ovens, left and right are containers for sweets, in the center is Shimazu Narikage Shogun porcelain chawan with purple glaze.

The world famous Satsuma porcelain appeared at the very end of the Edo period. Very often, its origin is associated with the name of the outstanding master Kinkozan Sobei VI (錦光山宗兵衛, 1823-1884) from the famous Kobayashi (小林) pottery dynasty in Awataguchi (Higashiyama district, Kyoto), who supplied utensils for the Buddhist Shoren temple, which is closely associated with the imperial family. , as well as for the shogunate in Edo. The head of this workshop in the sixth generation, who studied under Aoki Mokubei, reached the highest level of skill in working with porcelain. Its thin-walled kin-nikishide (金錦手), creamy white porcelain with "brocade" painting, opened a new direction in working with this material.

, as well as for the shogunate in Edo. The head of this workshop in the sixth generation, who studied under Aoki Mokubei, reached the highest level of skill in working with porcelain. Its thin-walled kin-nikishide (金錦手), creamy white porcelain with "brocade" painting, opened a new direction in working with this material.

pictured: works by Kinkozan Sobei

After the turmoil at the end of the Edo period and the reforms of the subsequent Meiji government, the Kobayashi family lost the support of their patrons. In order to continue to engage in family craft, it was necessary to conquer new markets. Taking the creative pseudonym Sobei and changing his surname to Kinkozan (literally: "Golden Brocade"), the head of the house managed not only to preserve, but also to qualitatively develop the work of his ancestors.

The first official major presentation of Japanese art in the West was at the Paris "World's Fair" in 1867. Among the exhibits was Kinkozan porcelain, which literally captivated the European public.

in the photo: "Japanese Pavilion" at the Paris Exhibition, illustration in the newspaper "La Monde" dated October 12, 1867.

The "golden age" began for the Kinkozan dynasty. The total production area expanded to 4,000 square meters, and the number of workers employed in production reached 700. The flames of the furnaces did not go out day and night.

Pictured: kilns at Miyaka no Shikagake, illustration from 1883 chronicle, from the Kyoto Prefecture Archives

Kinkozan Sobei was perhaps the most famous, but by no means the only gifted porcelain artist. On a par with him, you can put the names of such masters as Taizan Yohei (帯山与兵衛), Yabu Meizan (藪明山), Tin Jukan (沈寿官), Miyagawa Kozan (Makuzu, 宮川香山), Seikozan (精巧山) and Ryozan (亮山).

in the photo: works by Yabu Meizan

The photo: works by Tin DZYUKAN

in the photo of Tyazan Yohey

at the photo: works of Makuzzu

Photo: Seikozan's works

in the photo: Redzan's works

Demand for Kin-Nishide led to the emergence of many workshops that were released in Kyoto, Ikoogam, Nara, Osaka and other other areas. Most of them painted blanks, “linen” from Satsuma, where the largest deposits of porcelain stone in the region were located. The term Satsuma transcended geography and came to refer to a particular artistic style with which Japan as a whole was strongly associated in the West.

Most of them painted blanks, “linen” from Satsuma, where the largest deposits of porcelain stone in the region were located. The term Satsuma transcended geography and came to refer to a particular artistic style with which Japan as a whole was strongly associated in the West.

Porcelain in the Satsuma style, late 19th century

Above the glaze, the items were painted with enamels and gold paint suikin (borrowing a technique invented at the Meissen manufactory in Germany). Strikingly fine, detailed painting covered both external and internal surfaces. Illustrations on the theme of literary works and battle scenes, episodes from the life of Buddhist arhats, landscapes and famous views of the ancient capital of Kyoto fit into cartouche frames superimposed on traditional fabric patterns or abstract ornaments. In addition to painting, the products were decorated with elements of openwork carving or made in high relief moriaji depictions of plants, birds, and dragons, or the coat of arms of the Shimazu clan.

in the photo: Satsuma style porcelain, late 19th century

As for utilitarian purposes, the lion's share of all production fell on vases - the shapes and decor of which amaze with their variety and virtuosity of execution.

From the tiny ones that fit in the palm of your hand to the one and a half meter floor, painted so skillfully that they can compete with the paintings of the most famous painters, today they are especially loved by collectors and are frequent guests of all kinds of auctions.

were also in great demand in Europe tea and coffee sets ...

... Cups and dishes ...

... Teapers, candy and caskets ...

... as well as more authentic items - censuses and cells for cells for singing crickets.

In the first half of the twentieth century, due to wars and economic crises, the demand for luxury goods from the Land of the Rising Sun fell significantly. Many workshops closed, and those that continued to work reduced the price of their products to the detriment of their quality, so by the 50s, Satsuma products had finally lost their former attractiveness. And only at the end of the twentieth century, fine art began to gradually revive.

Many workshops closed, and those that continued to work reduced the price of their products to the detriment of their quality, so by the 50s, Satsuma products had finally lost their former attractiveness. And only at the end of the twentieth century, fine art began to gradually revive.

pictured: contemporary work

Satsuma marking

Satsuma porcelain was not marked until the 1970s. On products of subsequent years, as a rule, there is the name of the workshop, the signature of the master and, sometimes, additional marks. For example, on products of the Meiji era (1868-1912) there is a mark "Dai Nihon" (大日本, "Great Japan").

One of the characteristics of Satsuma is kamon (family crest) of clan Shimazu (Satsuma shoguns): a cross inscribed in a circle. Initially, such a seal indicated that the product belonged to representatives of this family, but in the era of mass production it became just an element of marketing.

Go to section Antique Japanese porcelain of our online store

Marks of Russian antique porcelain. Hallmarks of porcelain factories in Russia

The first hallmarks in Tsarist Russia

Types of hallmarks on porcelain from Tsarist Russia

Two hallmarks

Problems identifying hallmarks

Peculiarities of hallmarks from the Soviet period

First hallmarks in Tsarist Russia

In Russia, the need to use hallmarks appeared as soon as the first porcelain factories were opened. Until the middle of the eighteenth century, Russia could only dream of its own porcelain production, until the incredible diligence of Dmitry Ivanovich Vinogradov at the first porcelain manufactory in the country led to the discovery of a recipe for Russian porcelain. In 1747-1749years, the first successful products appeared, which began to be branded with the letter W (the initial letter of Vinogradov's surname) and the year of manufacture of the product.

There were no standards for the first hallmarks, so they differed from each other in size, location and style of signs. Even then, the tradition of indicating the place of production and the number of the recipe for porcelain mass began to emerge.

With the transformation of the Neva Porcelain Manufactory into the Imperial Porcelain Factory, the opening of the F.Ya. Gardner and other hallmarks helped to distinguish one porcelain product from another. Moreover, enterprising people not only began to massively open their own porcelain establishments, but also actively created fakes of products from famous factories, which led to the need to create high-quality hallmarks.

The problem began to acquire a mass character not only within the country, since there was a need to distinguish Russian porcelain from foreign. To this end, several decrees were issued at different times describing the procedure for hallmarking porcelain products. In particular, decrees issued from the middle of the 18th to the middle of the 19th century prescribed that the owner of the factory and its location should be indicated in the hallmarks. At the same time, the product must have had a Russian brand, even if another brand was supposed to be for foreign markets. Since 1857, the hallmarks had to be made with red paint.

In particular, decrees issued from the middle of the 18th to the middle of the 19th century prescribed that the owner of the factory and its location should be indicated in the hallmarks. At the same time, the product must have had a Russian brand, even if another brand was supposed to be for foreign markets. Since 1857, the hallmarks had to be made with red paint.

All these requirements left a significant imprint on the hallmarks of Russian porcelain, although they were not an indisputable truth for small manufacturers. Many did not disdain to violate the established rules in every possible way, therefore, on porcelain produced in the Russian Empire, there are many hallmarks in a variety of designs.

Types of stamps on porcelain of Tsarist Russia

Application options

Traditionally in Russia, several methods of hallmarking porcelain were used. Overglaze and underglaze hallmarks were very common. The first of them were placed on top of the fired glaze, and the second - before it was applied, so they were preserved better than the first. A more reliable method of branding, which was more difficult to fake, is considered to be indentation into a mass of unbaked clay. However, the payoff for reliability with this method is reduced artistic capabilities.

A more reliable method of branding, which was more difficult to fake, is considered to be indentation into a mass of unbaked clay. However, the payoff for reliability with this method is reduced artistic capabilities.

Image complexity

The contents of the stamps were very diverse even at the same enterprise. In the first years of production, simple stamps in the form of one or more letters could be used, and in subsequent years they could move on to complex ornaments. For example, if the first hallmarks at the Dulevo Porcelain Factory were the abbreviations STK or ZSK, behind which the names of their owners were hidden, then later picturesque ornaments and a coat of arms were added to them, and the owner's surname began to be written in full. A similar practice existed at other Russian porcelain manufactories.

Royal symbols

The image of the Russian coat of arms was a privilege that only a few factories received. Such a right was given to those breeders whose porcelain products were especially singled out at exhibitions, noted at the Court. Producing porcelain of excellent quality, factories often received orders from the Imperial Court itself. These included the factory of the Kornilov brothers, the Gardner factory, the enterprises of Kuznetsov, Auerbach and some others. At the Kornilov factory, the Moscow coat of arms was painted with all care, using paints of different colors for one hallmark.

Such a right was given to those breeders whose porcelain products were especially singled out at exhibitions, noted at the Court. Producing porcelain of excellent quality, factories often received orders from the Imperial Court itself. These included the factory of the Kornilov brothers, the Gardner factory, the enterprises of Kuznetsov, Auerbach and some others. At the Kornilov factory, the Moscow coat of arms was painted with all care, using paints of different colors for one hallmark.

Most often, state paraphernalia was applied to expensive products or porcelain and earthenware that was intended for export. It was here that the coat of arms was depicted very subtly, carefully outlining every detail.

In addition to the emblem itself, the hallmarks depicted symbols of royal power. In particular, in the hallmarks of the world-famous Imperial Porcelain Factory, the crown was the most frequent element. She began to be depicted with the coming to power of Emperor Paul I and was used until the October Revolution, when, with the advent of Soviet power, all royal symbols were removed from the hallmarks. The crown was also depicted conditionally or painted with all care.

She began to be depicted with the coming to power of Emperor Paul I and was used until the October Revolution, when, with the advent of Soviet power, all royal symbols were removed from the hallmarks. The crown was also depicted conditionally or painted with all care.

Monogramming

A frequent practice in factories was the use of a monogram. For example, at the factory of the brothers Novykh and Khrapunov-Novoy, it consisted of the initials of the owners: Ivan Novy and then Yakov Khrapunov-Novoy. For Alexei Popov, the letter “A” smoothly turned into “P”, while for Andrei Miklashevsky, “A” merged with “M”.

Hallmarks with the initials of Andrei Miklashevsky (left) and Alexei Popov (right).

At the Imperial Porcelain Factory (IFZ), monograms were the initial letter of the monarch's name and the specific number of his title. For example, for Catherine II, the Roman deuce was written inside the capital letter E. Since many tsars have been on the Russian throne during the existence of the IPM, so there were hallmarks with monograms AI, AII, AIII, HI and others according to the names of the kings.

Since many tsars have been on the Russian throne during the existence of the IPM, so there were hallmarks with monograms AI, AII, AIII, HI and others according to the names of the kings.

Floral and other ornaments

The most frequent element of complex stamps, which were usually put on the highest quality products, are all kinds of floral and other ornaments. For example, from the second half of the 19th century, at the Khrapunov-Novoy plant, they began to use whole baskets of flowers with the name of the factory owner on the basket itself. At the Dulevo factory in the middle of the 19th century, a gold brand “ZSTK in Dulevo” appeared with a beautiful floral pattern. It was put only on expensive products. The hallmarks of many manufactories were framed with curls, enclosed in oval, round and other shapes.

Marks on the porcelain of the Novy brothers.

Variety of symbols

The hallmarks of Russian porcelain factories amaze with the variety of symbolism. Tsarist decrees prescribed to indicate the owner and address of the factory in the hallmarks, but did not prohibit expressing one's individuality. This was reflected in the fact that enterprises used their own symbols, one way or another characterizing their activities. For example, there is a family coat of arms in the hallmarks of the Miklashevsky factory, Yusupov had his own symbol in the hallmark, among other things, stars, orders and medals can be found on Kuznetsov porcelain, Gardner depicted a rider on a horse, and after the Great October Revolution attributes of the Soviet era appeared in the hallmarks.

Tsarist decrees prescribed to indicate the owner and address of the factory in the hallmarks, but did not prohibit expressing one's individuality. This was reflected in the fact that enterprises used their own symbols, one way or another characterizing their activities. For example, there is a family coat of arms in the hallmarks of the Miklashevsky factory, Yusupov had his own symbol in the hallmark, among other things, stars, orders and medals can be found on Kuznetsov porcelain, Gardner depicted a rider on a horse, and after the Great October Revolution attributes of the Soviet era appeared in the hallmarks.

Stamp of the Miklashevsky factory with the family coat of arms.

Information about heirs

Since successful porcelain enterprises existed for several decades and even centuries, several owners changed during their work. If the former owner of the factory managed to achieve significant success and glorify his porcelain, the new owner tried to keep his name or used transitional hallmarks. For example, the descendants of the manufacturer Batenin used the inscription "NASL: BATEN", denoting Batenin's heirs. Kuznetsov, who bought out the dilapidated Auerbach plant, for some time used the brand “Former. Auerbach" to keep the old clientele. And Yakov Khrapunov completely decided to take a different surname after he entered into the right to own the plant of his wife Novaya.

For example, the descendants of the manufacturer Batenin used the inscription "NASL: BATEN", denoting Batenin's heirs. Kuznetsov, who bought out the dilapidated Auerbach plant, for some time used the brand “Former. Auerbach" to keep the old clientele. And Yakov Khrapunov completely decided to take a different surname after he entered into the right to own the plant of his wife Novaya.

Special notes

At many factories, special notes were made in the hallmarks, which could only be explained by the factory masters themselves. In some cases, these were designations of the addressee to whom this or that service or figurine was intended. At the IPM, for this, a “PK” mark was made, indicating that specific products were created for the court office. The Kornilovs had a mark “ON SPECIAL. ORDER". By the way, it is at the Kornilov factory that there is an inscription on porcelain about the prohibition of reproduction, which was the first attempt in Russia to protect the rights of authors to porcelain products.

If the factory experimented with porcelain mass, then they could put on the products the number of a specific recipe or make other notes related directly to the production.

On some products there are names of porcelain masters in the form of initials or full names. So, at the Yusupov factory, the signature of the master Lambert is found on porcelain. However, the talented painter of the Sevres manufactory not only contributed to the flourishing of the Yusupov factory, but also owned it for some time. On the IPM, hallmarks with the names of masters are found approximately from the middle of the 19century. The more famous the master was, the more expensive the product with his name was valued.

Signature and monogram Lambert

on Yusupov's porcelain.

Two hallmarks

On a number of porcelain works there are two hallmarks at once. There are several reasons for this phenomenon. The first is that the master simply could not make the stamp with sufficient pressure the first time. Then he put another one, trying to get into the previous one or in a new place. Since the attempt to put one brand into another did not always end with the desired result, fuzzy brands with double characters appeared. An example is Batenin's porcelain.

The first is that the master simply could not make the stamp with sufficient pressure the first time. Then he put another one, trying to get into the previous one or in a new place. Since the attempt to put one brand into another did not always end with the desired result, fuzzy brands with double characters appeared. An example is Batenin's porcelain.

The second reason was that the linen (glazed porcelain without painting) was made by one factory, and the painting was completely different. So, at the factory of the Kornilov brothers, twice a year they sold low-quality porcelain, including linen. As a result, the stamp of the porcelain manufacturer and the master of painting appeared on the final products. Some factories were not engaged in the manufacture of porcelain mass, but simply purchased blanks and painted them. In particular, this was done in the workshop of Prince Yusupov, who purchased linen from Popov, Gardner and other large breeders.

Another reason was related to the need to move from one period to another. Most often, this referred to a change of ownership, which had already managed to make itself known in the porcelain market. In order not to lose the old customers, the new owner put a new brand next to the old one, in which his name already appeared.

Most often, this referred to a change of ownership, which had already managed to make itself known in the porcelain market. In order not to lose the old customers, the new owner put a new brand next to the old one, in which his name already appeared.

There were other reasons for putting two hallmarks, for example, they were put on products intended for export.

Problems identifying marks

Until now, specialists have to make a lot of efforts to classify this or that product to a particular plant. This is due not only to the low quality of hallmarks or their absence, but also to the desire of small workshops to imitate eminent enterprises.

Small establishments often failed to achieve high quality porcelain, so that a trained eye quickly distinguished a fake. However, there were cases when fakes were obtained at the level of the original. In particular, the Safronov plant began by imitating the famous products of the Gardner factory. There is a version that it is with this imitation that the fact that in the early years of the existence of the Safronov plant they used exactly the same hallmarks in the form of a hook-shaped letter “C” was used on it, as well as at the well-known Gardner plant at that time. At the Gardner plant at one time, the letter G began to look like a "C".

There is a version that it is with this imitation that the fact that in the early years of the existence of the Safronov plant they used exactly the same hallmarks in the form of a hook-shaped letter “C” was used on it, as well as at the well-known Gardner plant at that time. At the Gardner plant at one time, the letter G began to look like a "C".

Interestingly, over time, the Safronov factory gained its own fame thanks to good quality porcelain and original artistic painting. At that time, at one of the Moscow exhibitions, the products of the plant were described as those that deserve approval and praise. At the beginning of the 19th century, according to its artistic value, Safronov's porcelain was in third place after the eminent factories of Popov and Gardner.

Russian factories imitated the brands not only of their compatriots, but also of foreign manufactories. For example, at the Gardner factory in 1770–179In the early 1900s, they used the mark with the image of crossed swords, which is typical for Meissen porcelain. This symbol was used in various variations, including one in which the letter G was present.

This symbol was used in various variations, including one in which the letter G was present.

Another problem was the peculiarities of the hallmarks themselves or their erasure over time. For example, some hallmarks on the Batenins' porcelain can be distinguished only if the light source is directed very slowly towards the product, changing the angle of inclination.

Overglaze marks were poorly preserved and were easily forged, while those pressed into the mass often depended on the quality of the stamp and the force of pressure. Moreover, many original works do not have any designations at all. This applies, for example, to the products of the Yusupov plant. The prince created his workshop, having no commercial interest, and therefore there was no need for hallmarks. Most of Yusupov's products came to his estate or were donated by the prince to noble persons.

Features of stamps of the Soviet period

After the October Revolution in 1917, mass nationalization of porcelain enterprises began. Some of them completely ceased to exist immediately after the advent of Soviet power, others were renamed and continued their work. The first thing that changed in the hallmarks of this period was the complete disappearance of the symbols of royal power. The only reminder was a double-headed eagle without royal paraphernalia, which for some time was present in the hallmarks of the IPE. Note that the stamp with the date 1917 were installed only during the period of the Provisional Government. At this time, a small number of items with such a stigma were released, so their collection value is high.

Some of them completely ceased to exist immediately after the advent of Soviet power, others were renamed and continued their work. The first thing that changed in the hallmarks of this period was the complete disappearance of the symbols of royal power. The only reminder was a double-headed eagle without royal paraphernalia, which for some time was present in the hallmarks of the IPE. Note that the stamp with the date 1917 were installed only during the period of the Provisional Government. At this time, a small number of items with such a stigma were released, so their collection value is high.

Now the hammer and sickle have replaced the kings with their crowns and sceptres. Stars, ears of wheat, the image of the globe and other elements typical of the Soviet period were used in almost every factory. And the former names of the owners have replaced numerous abbreviations and new names of enterprises. Thus, the IFZ turned first into the GFZ, and then into the LFZ. Hallmarks with the inscription LFZ are known to many, since porcelain was branded with their help for eighty years from 1925 to 2005.

Hallmarks with the inscription LFZ are known to many, since porcelain was branded with their help for eighty years from 1925 to 2005.

The abbreviations referred not only to the new names of factories, but also to various organizations that emerged from them, or those through which porcelain was sold. This is how the inscriptions Mosoblgorspetstorg, Glavunivermag, abbreviations TD (trading house), TF (Tver porcelain), TsFFT (Centrofarforforrest) and many others appeared.

Of particular interest to collectors around the world is the so-called propaganda porcelain, which has practically no analogues. Its origin is connected with the no less interesting plan of "monumental propaganda" called for by V.I. Lenin. The meaning of this propaganda was to move as soon as possible from everything that symbolized tsarist Russia to the Russia of workers and peasants. However, in practice, propaganda porcelain turned out to be too expensive for the common man and ended up in collectors' collections. Moreover, over time, the interest of foreign collectors in it has grown so much that the price of such items has risen several times.

Moreover, over time, the interest of foreign collectors in it has grown so much that the price of such items has risen several times.

Agitation porcelain is characterized by a variety of appeals and slogans: "The kingdom of the workers and peasants will have no end!", "Long live Soviet power!" etc. As for the hallmarks, their main elements were the crossed hammer and sickle. There are also some inscriptions in the hallmarks, for example, “For the benefit of the starving”.

If in tsarist Russia the hallmarks of the same factory differed greatly in letter size, style of writing, drawing, and generally depended on the mood of the master, then the hallmarks of the Soviet period are characterized by the same letter size, stencilling, and sufficient clarity of images. Still, the mechanization of production has left its mark on the quality of stamps.

Hallmarks of the Dulevo Porcelain Factory.

Another characteristic element for the hallmarks of Soviet porcelain is the words in Latin letters with the designation of the country: USSR or SOVIETUNION, as well as the postscript made in. In the same theme and the brand Torgsin, denoting "Trade Syndicate". Before the revolution, each plant itself came up with what the stamps for export should be. Some used inscriptions in French, others depicted arabesques and other elements for oriental clients. There was also a practice of using the inscription Made in Russia, the first use of which belongs to the factory of the Kornilov brothers.

In Soviet times, stamps often indicated the group of complexity of the drawing and the grade of the product. For example, at the LFZ, different colors were used to designate one or another variety, and the varieties themselves were designated as “1 s”, “2 s”, “3 s”. For groups, the signs "6 gr", "7 gr", etc. were used. or "OUT OF GR" for a particularly high-end product.