19Th century garden plants

Victorian Garden Plants | How to Make a Victorian Garden

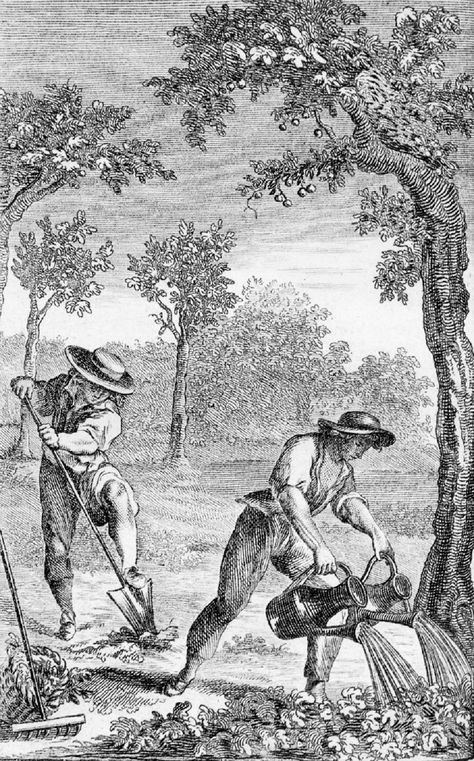

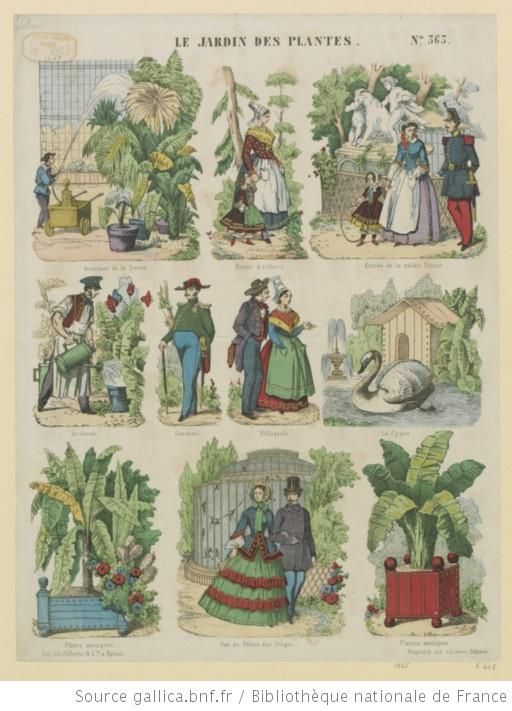

While the fascination with gardening has been going on since Eden, it was during the nineteenth century Victorian era that gardening became widely popular due in part to new technologies, more diverse plant stock, and the rise of the middle class and, with it, the invention of suburban living. Nevertheless, the number one reason gardening increased in popularity during the 1800s was the rise in the amount of leisure time middle class men and women could devote to it.

The underlying theme of the Victorian garden, as in much of Victorian life in general, was man's conquest over the elements. Nothing exemplifies this so much as the lawn. Thanks to the efforts of the seed companies and nurseries, the lawn became one of the most noted features of the American landscape, appearing in cities and towns from Maine to California.

If you've ever had to maintain an average-sized lawn you know how much time it takes -- a "perfect" lawn requires constant attention. Once lawn perfection had been attained, our Victorian forebears sought to embellish it, and did so by attempting to turn their lawns into outdoor parlors. Indoor parlors needed to be decorated and so did those out-of-doors. There are eight essential elements of a late Victorian garden, including Victorian Garden plants.

Lawn: A front and rear lawn were considered imperative in a formal garden. Cottage gardens and woodland gardens were more informal, and lawns were not such a requisite. The large expanses of lawn on estates were trimmed by gang mowers, drawn by horses. The push mower, for more modest lawns, was patented during Victoria's reign. Today a landscape designer can go mobile in designing their outdoor space by using a landscape app. Landscape design apps allow users to visualize and then create a design from scratch on the iPad using a photo taken with the tablet’s camera.

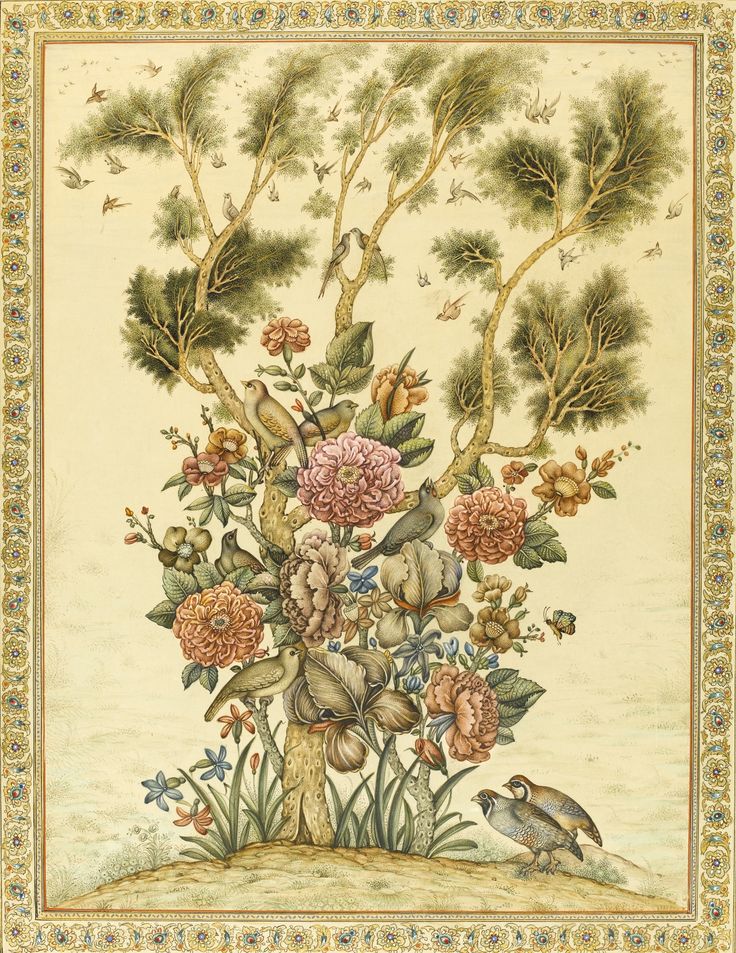

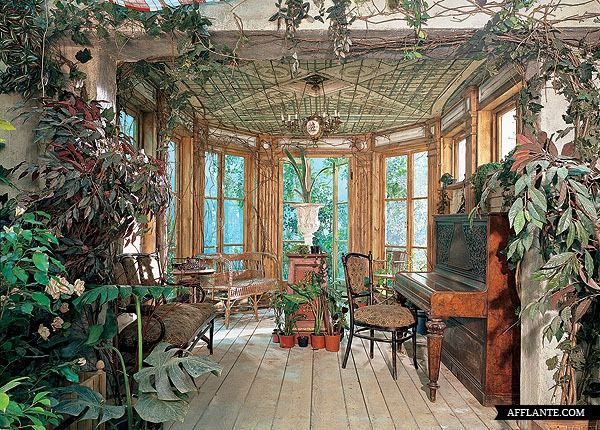

Trees: Trees were used primarily to shade important parts of the house where direct sun was unwelcome, such as a dining room or veranda. Trees were also used to frame the carriage drive or approach to the house. In the city, trees were often planted along the street to aid in privacy. Weeping trees and those with interestingly colored or shaped leaves were popular and used strategically to draw the eye. Depending upon climate, one might collect exotic trees and "display" them as part of the lawn decor. Most often these exotics were kept in conservatories.

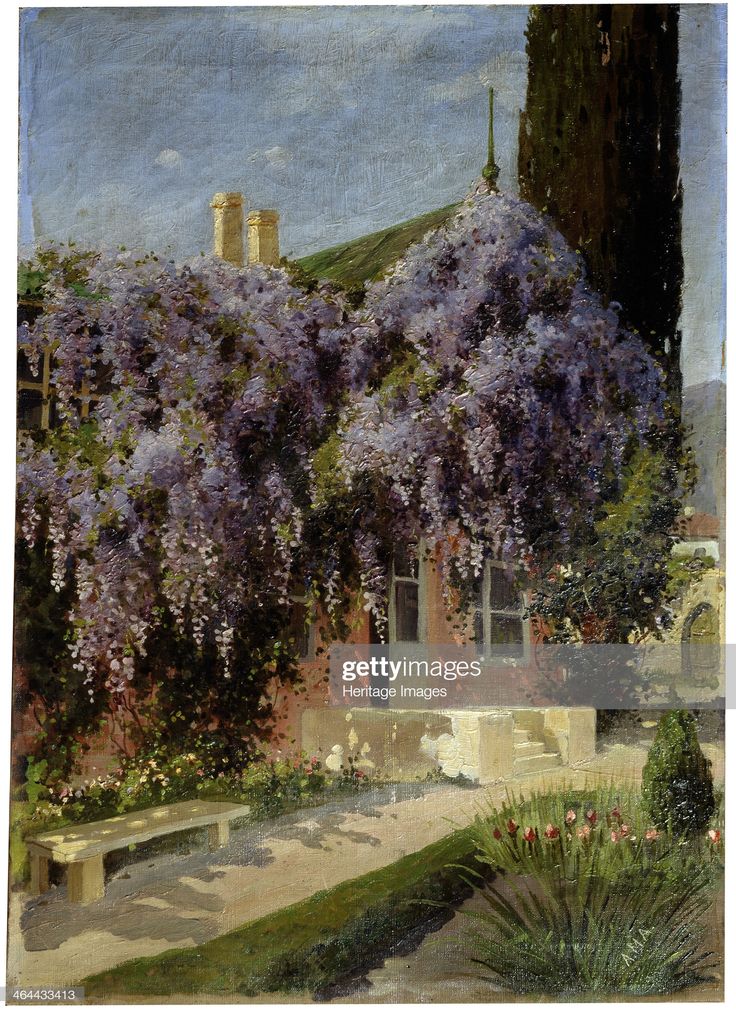

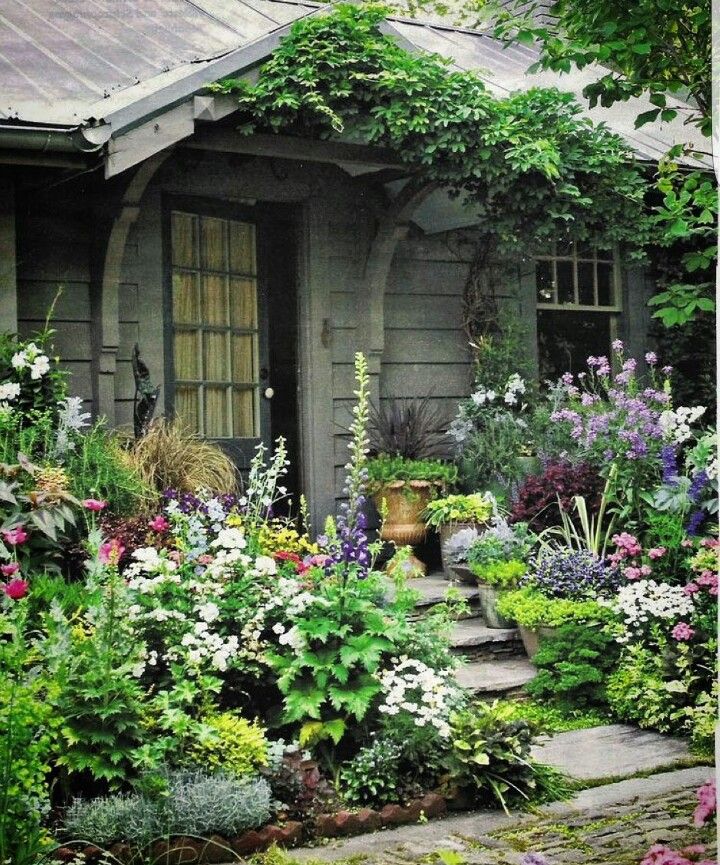

Shrubs: Shrubs were used mainly for delineating property lines or marking paths. They might also be used to hide an "unsightly" wooden fence or house foundation, or used to frame doorways or bay windows. It was popular to mix the species of shrubs.

Fencing: Most properties at the turn of the century were fenced. Cast iron was by far the most popular material because it was the most ornamental and was also used for outdoor furniture. The more elaborate the home, the more elaborate (usually) the fence and gate. In more informal settings, rustic fencing was used. This might be made of "rustic" wood bent into decorative motifs. The picket fence was to be hidden with shrubs at best, or vines if shrubs were out of the question.

Cast iron was by far the most popular material because it was the most ornamental and was also used for outdoor furniture. The more elaborate the home, the more elaborate (usually) the fence and gate. In more informal settings, rustic fencing was used. This might be made of "rustic" wood bent into decorative motifs. The picket fence was to be hidden with shrubs at best, or vines if shrubs were out of the question.

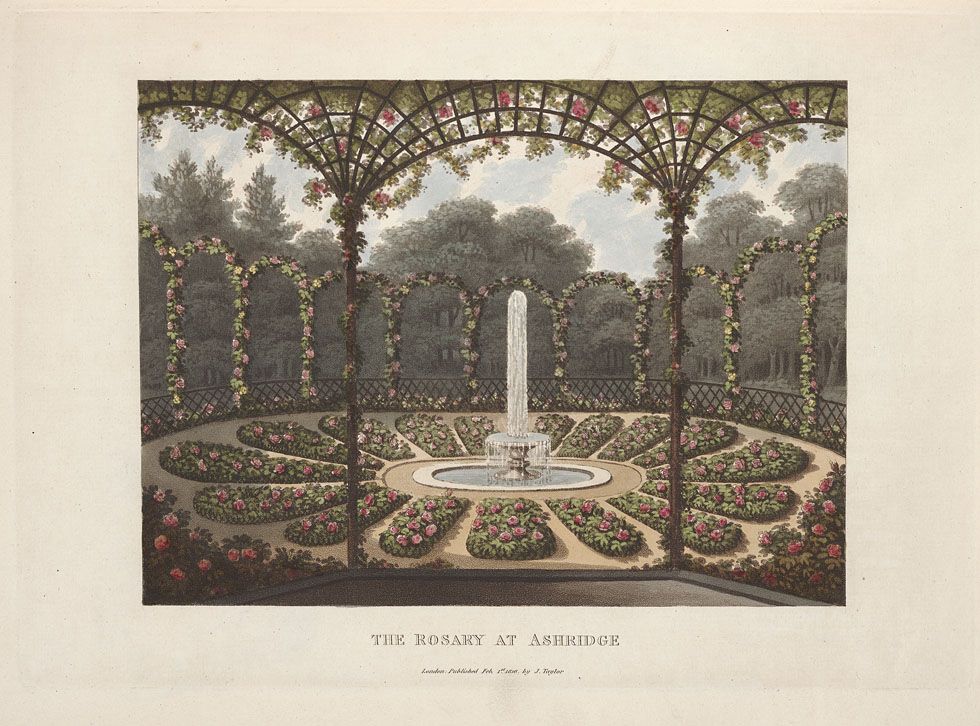

Ornaments: Urns, sculpture, garden water fountains, sundials, gazing balls (lawn balls), birdbaths, and man-made fish ponds were all commonly used. Cast iron was a commonly used material for such accoutrements. Often, urns were not planted with anything, but were simply set in pairs to ornament stairs or balustrades.

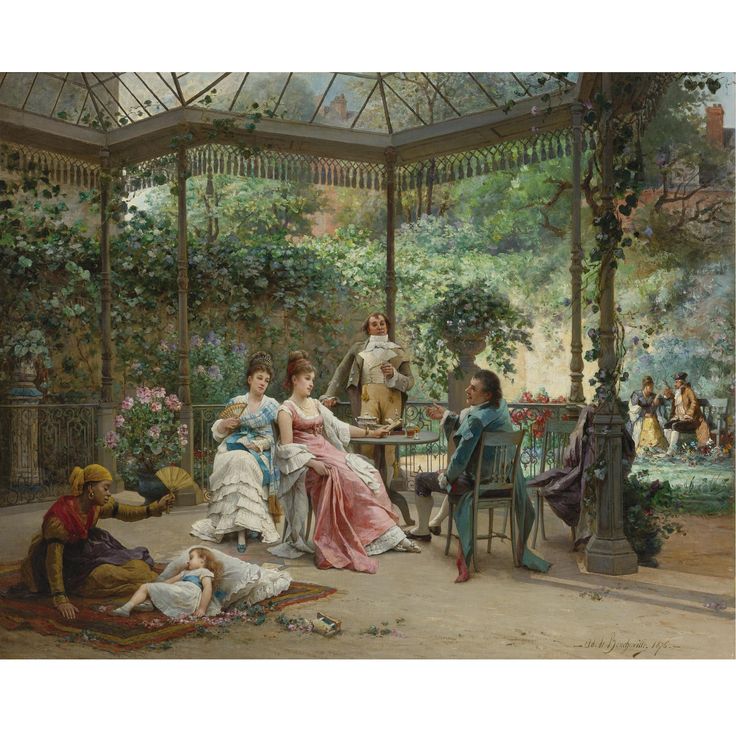

Seating: Garden benches, seats, pavilions, garden seat trellis designs and gazebos were made as decorative as possible. Cast iron or "rustic" wood were the most commonly used materials. Seats were placed under trees along garden walks, and of course in pavilions and gazebos. Rattan and wicker furniture was used mainly on porches and in sun rooms of the house.

Cast iron or "rustic" wood were the most commonly used materials. Seats were placed under trees along garden walks, and of course in pavilions and gazebos. Rattan and wicker furniture was used mainly on porches and in sun rooms of the house.

Victorian Garden Plants

| Cottage Garden | English Landscape Gardens |

| Window Box Ideas | Garden Walkways |

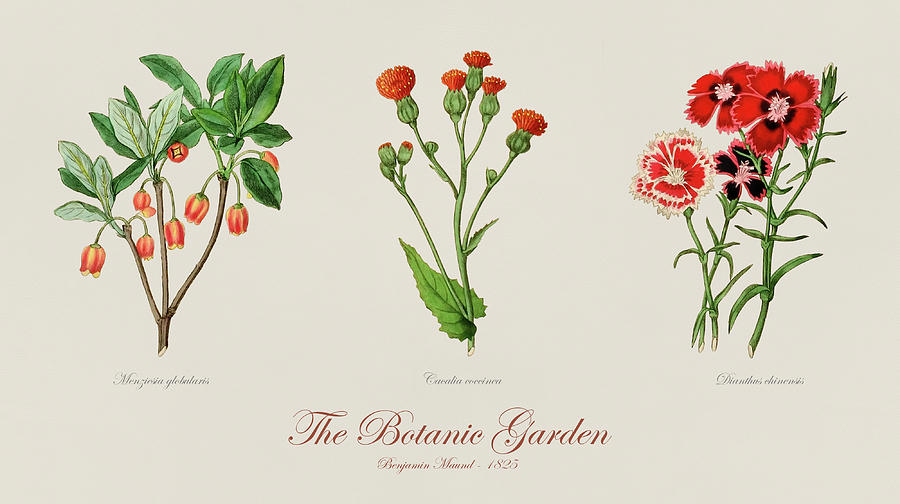

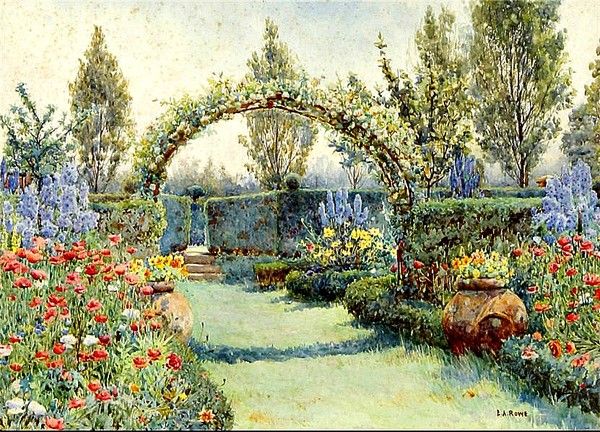

Flowers and Plants: Carpet bedding, the use of same-height flora, was popular. Most often used to depict a motif or design (such as the floral clock in Niagara Falls, Canada), carpet bedding came under attack by gardeners like Gertrude Jekyll, who thought that each flower and plant should be grown for its intrinsic beauty and not as part of a "carpet." Jekyll's idea of an "herbaceous border" called for flowers of varying heights. Usually planted along a shrub border, wall, or garden path, the herbaceous border began with the shortest plants in the front. Each successive row of flowers would be taller than the last, with the tallest plants at the back. Rose garden designs were extremely popular and climbing varieties were often trained over a trellis, bower or pergola. Urban dwellers without much of a yard would often plant large urns beside the front door with flowers or small shrubs. Flowers could also be planted along the front walk underneath the shrubs which bordered it.

Most often used to depict a motif or design (such as the floral clock in Niagara Falls, Canada), carpet bedding came under attack by gardeners like Gertrude Jekyll, who thought that each flower and plant should be grown for its intrinsic beauty and not as part of a "carpet." Jekyll's idea of an "herbaceous border" called for flowers of varying heights. Usually planted along a shrub border, wall, or garden path, the herbaceous border began with the shortest plants in the front. Each successive row of flowers would be taller than the last, with the tallest plants at the back. Rose garden designs were extremely popular and climbing varieties were often trained over a trellis, bower or pergola. Urban dwellers without much of a yard would often plant large urns beside the front door with flowers or small shrubs. Flowers could also be planted along the front walk underneath the shrubs which bordered it. Window boxes were also popular. If your want to design your own Victorian garden, download free landscape design software. You can choose bushes and shrubs; design a flower garden, layout a sprinkler system … all on your computer.

Window boxes were also popular. If your want to design your own Victorian garden, download free landscape design software. You can choose bushes and shrubs; design a flower garden, layout a sprinkler system … all on your computer.

Vines of all types were used as decoration and to hide "unsightly" features, such as fences and tree stumps. Vines could also be trained up the side of a porch to ward off the sun.

Plant Companies:

Old-fashioned types of flowers and plants are fairly common today. Some companies pride themselves on their collections of antique or heritage seeds that many hybrids sprang from. Check with your local plant seller for old-fashioned Victorian garden plant varieties. In the US, there are several companies from which seeds and plants of old-fashioned varieties may be purchased.

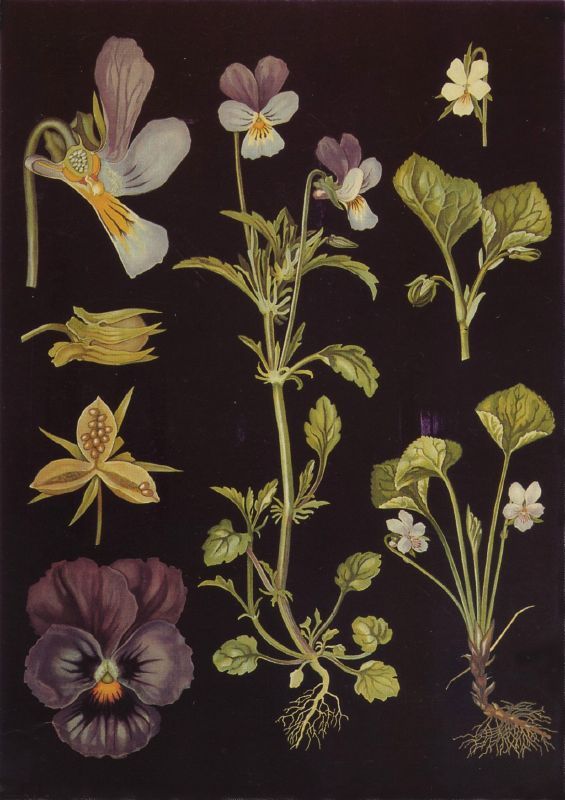

Some Victorian garden plants that are generally available for summer gardens and that will also do well in containers: Acacia, Ageratum, Alonsoa, Amanthus, Aster, Scarlet Basil, Begonia Tuberous, Begonia, Bluebell, Caladium, Calendula, Campanula, Chrysanthemum, Cobaea, Cockscomb, Coleus, Dianthus, Dusty Miller, Fern, Fuschia, Geranium, Scented Geranium, Heliotrope, Impatiens Lobelia Marigold, Moonflower, Morning Glory, Nasturtium, Oxalis Pansy, Periwinkle, Petunia, Portulaca, Primrose, Rose, Miniature Rose, Snapdragon, Sweet Alyssum, Thunbergia, Verbena, Zinnia. ("Grandmother's Flowers".

("Grandmother's Flowers".

About Author: Cheryl Hurd has been writing about the late Victorian Era for many years, and is the author of several "little books for Victorian pursuits", including Dressing up Victorian and the Victorian Yellow Pages, a mail order resource for Neo-Victorians. Cheryl was also invited to lecture on Victorian domesticity at the Carnegie Museum in Pittsburgh, PA.

Use a Garden Planner for Your Own Design

In planning your own garden, there are several ways to use your computer or iPad. Not all people have enough horticultural expertise to choose plants and arrange them for best results, but with free garden design software, you can try out this option. You can also design your own garden online with a free garden planner. With a kitchen garden planner, you can design your vegetable garden online by drawing your garden layout and click to place the crops where they want to grow them.

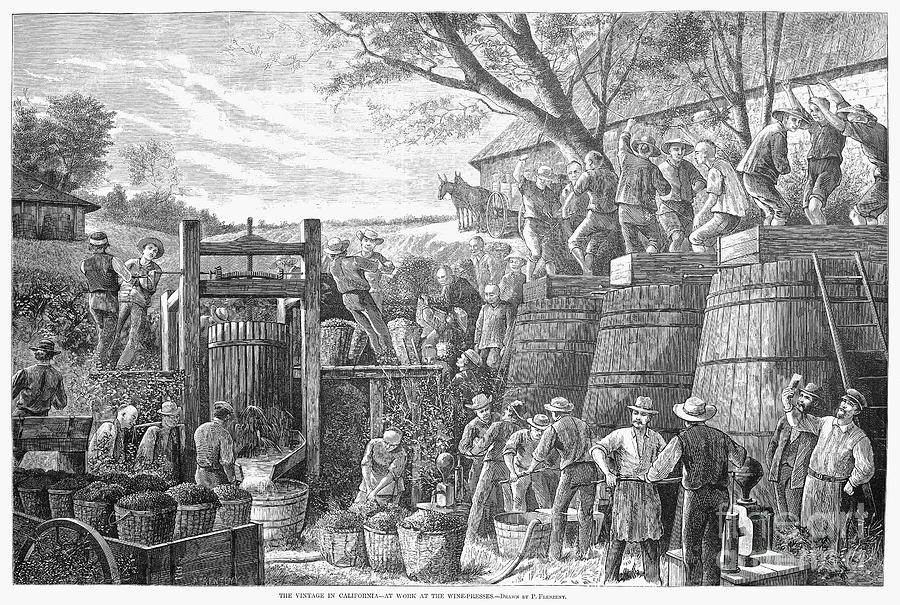

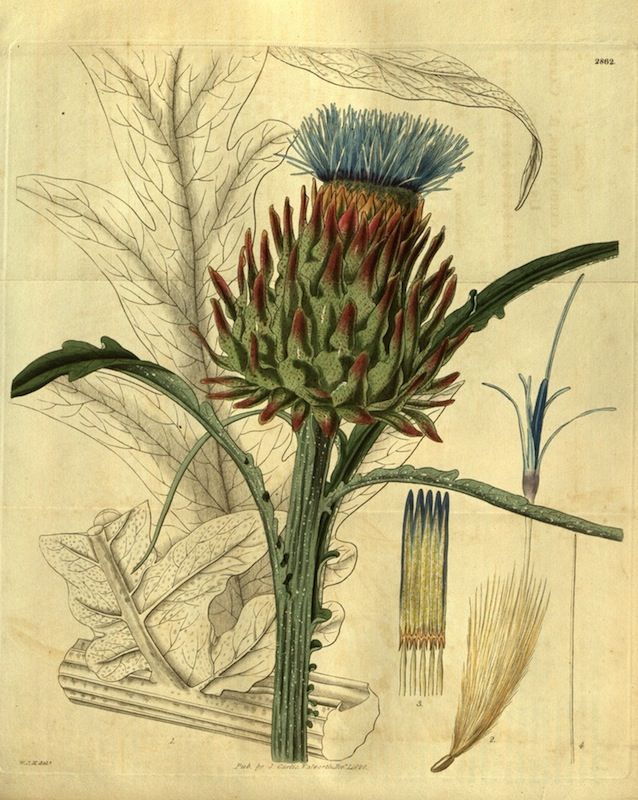

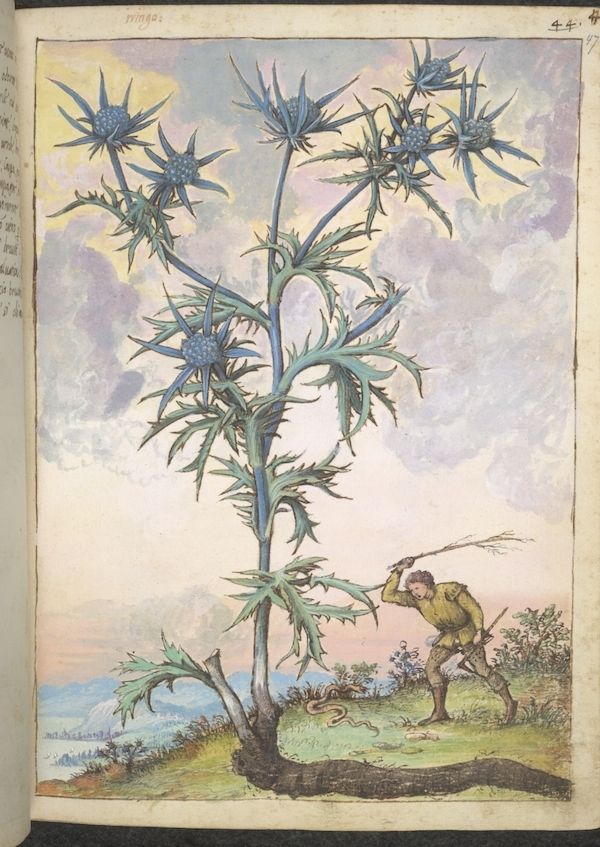

garden and landscape design - 19th century

Increasing world trade and travel brought to late 18th-century Europe a flood of exotic plants whose period of flowering greatly extended the potential season of the flower garden. Although the emphasis in Italian Renaissance gardens, in the Classical Baroque gardens of France, in the lawns and gravelled walks of 17th-century England, and in the Brownian park garden was upon design, they had rarely been totally without flowers. In most gardens flowers were grown, sometimes in great numbers and variety, but flower gardens in the modern sense were limited to cottages, to small town gardens, and to relatively small enclosures within larger gardens. The accessibility of new plants, together with avidity for new experience and a high-minded concern with natural science, not only gave renewed life to the flower garden but was the first step toward the evolution of the garden from work of art to museum of plants. A compromise between the new flower garden and the Brownian park was effected by Humphry Repton. He was largely responsible for popularizing the open terrace overlooking the park, which frankly admitted the different functions of park and garden and also emphasized their stylistic disharmony. The plant collectors’ garden, or “gardenesque” style, was most strongly advanced by J.C. Loudon in the mid-19th century. Loudon urged that garden making be taken out of the hands of the architect, the painter, and the cultivated dilettante and left to the professional plantsman.

A compromise between the new flower garden and the Brownian park was effected by Humphry Repton. He was largely responsible for popularizing the open terrace overlooking the park, which frankly admitted the different functions of park and garden and also emphasized their stylistic disharmony. The plant collectors’ garden, or “gardenesque” style, was most strongly advanced by J.C. Loudon in the mid-19th century. Loudon urged that garden making be taken out of the hands of the architect, the painter, and the cultivated dilettante and left to the professional plantsman.

The undiscerning use of the new palette that importation and plant breeding had made available was so patently an aesthetic disaster that by the end of the 19th century attempts were made to break its hold. The architect Sir Reginald Blomfield advocated a return to the formal garden, but to this, insofar as it required dressed stonework, there were economic objections. More successful and more in tune with the escapist needs of the increasing number of urban dwellers were the teaching and practice of William Robinson, who attacked both the old ceremonial garden and the collectors’ garden with equal vigour and preached that botany was a science, but gardening was an art. Under his leadership a more critical awareness was brought to the planning and planting of gardens. His own garden at Gravetye Manor demonstrated that plants look best where they grow best and that they should be allowed to develop their natural forms. Adapting Robinson’s principles, Gertrude Jekyll applied the cult of free forms over a substructure of concealed architectural regularity, bringing the art of the flower garden to its highest point.

Under his leadership a more critical awareness was brought to the planning and planting of gardens. His own garden at Gravetye Manor demonstrated that plants look best where they grow best and that they should be allowed to develop their natural forms. Adapting Robinson’s principles, Gertrude Jekyll applied the cult of free forms over a substructure of concealed architectural regularity, bringing the art of the flower garden to its highest point.

In North America, where for a long time most men were preoccupied with making a world, not a garden, ornamental gardens were slow to take hold. In the gardens that did exist, the rectilinear style popular in late 17th- and early 18th-century Europe persisted well into the 18th century—perhaps because it met man’s psychological need to feel he could master a world that was still largely untamed. The town gardens of Williamsburg (begun in 1698) were typical of the Anglo-Dutch urban gardens that were being attacked everywhere in 18th-century Europe except Holland. And Belmont, in Pennsylvania, was laid out as late as the 1870s with mazes, topiary, and statues, in a style that would have been popular in England about two centuries before.

And Belmont, in Pennsylvania, was laid out as late as the 1870s with mazes, topiary, and statues, in a style that would have been popular in England about two centuries before.

Although garden improvers set up in business in the United States, there is no evidence that they prospered until the 19th century, when one hears of André Parmentier, a Belgian, who worked on Hosack’s estate at Hyde Park and then of A.J. Downing, a successful protagonist of the gardenesque, who was succeeded by Calvert Vaux and Frederick Law Olmsted (the latter the originator of the title and profession of landscape architect), the planners of Central Park (begun 1857) in New York City and of public parks throughout the country.

The eclecticism of the 19th century was universal in the Western world. Besides the gardens that were fundamentally Reptonian—that is, an attempted compromise between the Brownian park garden and the Loudonian flower garden—gardens of almost every conceivable style were copied; designing teams such as Sir Charles Barry, the architect, and William Eden Nesfield, the painter, in England, for example, produced Italianate parterres as well as winding paths through thickets.

Modern

A sense of history still played a part in 20th-century gardening. The desire to maintain and reproduce old gardens, such as the reconstruction of the 16th-century gardens of Villandry in France and the colonial gardens of Williamsburg in the United States, was not peculiarly modern (similar things were done in the 19th century), but, as humans increasingly need the reassurance of the past, the impulse may well continue. Attempts to create a distinctive modern idiom are rare. Gardens large by modern standards are still made, in styles that vary from a version of the grand early 18th-century manner at Anglesey Abbey in Cambridgeshire to an inflated Jekyllism crossed with gardenesque at Bodnant near Conway. An air either of controlled wilderness or of slightly run-to-seed orderliness is preferred. Modern public gardens, which have evolved from the large private gardens of the past, seek instant popular applause for the quantity and brightness of their flowers. In Brazil Roberto Burle Marx used tropical materials to give an air of contemporaneity to traditional modes of design. Gardens frequently reflect Japanese influence, particularly in America.

Gardens frequently reflect Japanese influence, particularly in America.

Most characteristic of the 20th century was functional planning, in which landscape architects concentrated upon the arrangement of open spaces surrounding factories, offices, communal dwellings, and arterial roads. The aim of such planning was to provide, at best, a satisfactory setting for the practical aspects of living. It was gardening only in the negative, “tidying up” sense, with little concern for the traditional garden purpose of awakening delight. So starved was the spirit of those living in heavily populated regions, however, that demands grew more insistent for gardening in the positive sense—for environmental planning with a chief goal not of facilitating economic activities but of refreshing the spirit.

Non-Western

Western gardens for many centuries were architectural, functioning as open-air rooms and demonstrating the Western insistence on physical control of the environment. Because of a different philosophical approach, Eastern gardens are of a totally different type.

China—which is to Eastern civilization what Egypt, Greece, and Rome are to Western—practiced at the beginning of its history an animist form of religion. The sky, mountains, seas, rivers, and rocks were thought to be the materialization of spirits who were regarded as fellow inhabitants in a crowded world. Such a belief emphasized the importance of good manners toward the world of nature as well as toward other individuals. Against this background, the Chinese philosopher Laozi taught the quietist philosophy of Daoism, which held that one should integrate oneself with the rhythms of life, Confucius preached moderation as a means of attaining spiritual calm, and the teaching of Buddha elevated the attainment of calm to a mystical plane.

Such a history of thought led the Chinese to take keen pleasure in the calm landscape of the remote countryside. Because of the physical difficulty of frequent visits to the sources of such delight, the Chinese recorded them in landscape paintings and made three-dimensional imitations of them near at hand. Their gardens were therefore representational, sometimes direct but more often by substitution, making use of similar means to recreate the emotions that choice natural landscapes evoked. The kind of landscape that appealed was generally of a balanced sort; for the Chinese had discovered the principle of complementary forms, of male and female, of upright and recumbent, rough and smooth, mountain and plain, rocks and water, from which the classic harmonies were created. The principle of scroll painting, whereby the landscape is exposed not in one but in a continual succession of views, was applied also in gardens, and grounds were arranged so that one passed pleasantly from viewpoint to viewpoint, each calculated to give a different pleasure appropriate to its situation. A refined and expectant aestheticism, which their philosophy had inculcated, taught the Chinese to ignore nothing that would prepare the mind for the reception of such experiences, and every turn of path and slope of ground was carefully calculated to induce the suitable attitude.

Their gardens were therefore representational, sometimes direct but more often by substitution, making use of similar means to recreate the emotions that choice natural landscapes evoked. The kind of landscape that appealed was generally of a balanced sort; for the Chinese had discovered the principle of complementary forms, of male and female, of upright and recumbent, rough and smooth, mountain and plain, rocks and water, from which the classic harmonies were created. The principle of scroll painting, whereby the landscape is exposed not in one but in a continual succession of views, was applied also in gardens, and grounds were arranged so that one passed pleasantly from viewpoint to viewpoint, each calculated to give a different pleasure appropriate to its situation. A refined and expectant aestheticism, which their philosophy had inculcated, taught the Chinese to ignore nothing that would prepare the mind for the reception of such experiences, and every turn of path and slope of ground was carefully calculated to induce the suitable attitude. As the garden was in effect a complex of linked, related, but distinct sensations, seats and shelters were situated at chosen spots so that the pleasures that had been meticulously prepared for could be quietly savoured. Kiosks and pavilions were built at places where the dawn could best be watched or where the moonlight shone on the water or where autumn foliage was seen to advantage or where the wind made music in the bamboos. Such gardens were intended not for displays of wealth and magnificence to impress the multitude but for the delectation of the owner, who felt his own character enhanced by his capacity for refined sensation and sensitive perception and who chose friends to share these pleasures with the same discernment as he had exercised in planning his garden.

As the garden was in effect a complex of linked, related, but distinct sensations, seats and shelters were situated at chosen spots so that the pleasures that had been meticulously prepared for could be quietly savoured. Kiosks and pavilions were built at places where the dawn could best be watched or where the moonlight shone on the water or where autumn foliage was seen to advantage or where the wind made music in the bamboos. Such gardens were intended not for displays of wealth and magnificence to impress the multitude but for the delectation of the owner, who felt his own character enhanced by his capacity for refined sensation and sensitive perception and who chose friends to share these pleasures with the same discernment as he had exercised in planning his garden.

Based on natural scenery, Chinese gardens avoided symmetry. Rather than dominating the landscape, the many buildings in the garden “grew up” as the land dictated. A fanciful variety of design, curving roof lines, and absence of walls on one or on all sides brought these structures into harmony with the trees around them. Sometimes they were given the rustic representational character of a fisherman’s hut or hermit’s retreat. Bridges were often copied from the most primitive rough timber or stone-slab raised pathways. Rocks gathered from great distances became a universal decorative feature, and a high connoisseurship developed in connection with their colour, shape, and placement.

Sometimes they were given the rustic representational character of a fisherman’s hut or hermit’s retreat. Bridges were often copied from the most primitive rough timber or stone-slab raised pathways. Rocks gathered from great distances became a universal decorative feature, and a high connoisseurship developed in connection with their colour, shape, and placement.

Although the troubled 20th century largely destroyed the old gardens, paintings and detailed descriptions of them dating from the Song dynasty (960–1279 ce) reveal a remarkable historical consistency. Nearly all the characteristic features of the classic Chinese garden—man-made hills, carefully chosen and placed rocks, meanders and cascades of water, the island and the bridge—were present from the earliest times.

Chinese gardens were made known to the West by Marco Polo, who described the palace grounds of the last Song emperors, during whose reign the arts were at their most refined. Other accounts reached Europe from time to time but had little immediate effect except at Bomarzo, the Mannerist Italian garden that had no successors. In the 17th century the English diplomat and essayist Sir William Temple, sufficiently familiar with travelers’ tales to describe the Chinese principle of irregularity and hidden symmetry, helped prepare the English mind for the revolution in garden design of the second quarter of the 18th century. Chinese example was not the sole or the most important source of the new English garden, but the account of Father Attiret, a Jesuit at the Manchu (Qing) court, published in France in 1747 and in England five years later, promoted the use of Chinese ornament in such gardens as Kew and Wroxton and hastened the “irregularizing” of grounds. The famous Dissertation on Oriental Gardening by the English architect Sir William Chambers (1772) was a fanciful account intended to further the current revolt in England against the almost universal Brownian park garden.

In the 17th century the English diplomat and essayist Sir William Temple, sufficiently familiar with travelers’ tales to describe the Chinese principle of irregularity and hidden symmetry, helped prepare the English mind for the revolution in garden design of the second quarter of the 18th century. Chinese example was not the sole or the most important source of the new English garden, but the account of Father Attiret, a Jesuit at the Manchu (Qing) court, published in France in 1747 and in England five years later, promoted the use of Chinese ornament in such gardens as Kew and Wroxton and hastened the “irregularizing” of grounds. The famous Dissertation on Oriental Gardening by the English architect Sir William Chambers (1772) was a fanciful account intended to further the current revolt in England against the almost universal Brownian park garden.

Influence of the West on Chinese gardens was slight. Elaborate fountain works, Baroque garden pavilions, and mazes—all of which the Jesuits made for the imperial garden at Yuanmingyuan (“Garden of Pure Light”)—took no root in Chinese culture. Not until the 20th century did European regularity occasionally become evident near the Chinese dwelling; at the same time, improved Western hybrids of plant species that had originated in the East appeared in China.

Not until the 20th century did European regularity occasionally become evident near the Chinese dwelling; at the same time, improved Western hybrids of plant species that had originated in the East appeared in China.

Garden plants on the open balcony in winter: mission possible?

EventsIdeasUseful little thingsGarden decorsLandscape designOtherTips

29.01.2018

Landscape design

Russian winter leaves little space for gardeners to express themselves. Of course, during this period, it remains possible to temporarily switch to indoor floriculture, in particular, the creation of plant compositions in flowerpots on city balconies and loggias.

Let's say right away - there are few solutions for the cold season, there are many difficulties. Even if you manage to choose frost-resistant plants that can grow well in pots in winter, alternating snowfalls and heavy rains threaten to negate the entire decorative effect of landscaping an open balcony.

Yet true gardening enthusiasts are up for the challenge! We have selected plants that can decorate an unglazed balcony in winter. So it is quite possible to create a frosty oasis that will not lose its charm even under a layer of snow.

Important! The vast majority of winter hardy plants do not tolerate stagnant water in the ground. Therefore, task number 1 is to choose the right pots for the balcony. It should have thick walls and good water and air permeability characteristics. Additional insulation of the pot inside will not hurt either. Terracotta and ceramic pots and planters are best suited, but glass and metal are best left until warmer times.

Heather

Of course, heat-loving indoor flowers on the balcony will not survive, but some types of plants tolerate winter conditions well, retaining their beauty and decorative effect. For example, heather is an evergreen perennial with a lilac-purple color that contrasts beautifully with white snow. In a garden in winter, heather requires shelter, as it is adversely affected by excessive moisture during thaws. But the atmosphere of the city balcony is quite to his liking - it is enough to transplant a heather bush into a planter and provide a "roof over his head."

In a garden in winter, heather requires shelter, as it is adversely affected by excessive moisture during thaws. But the atmosphere of the city balcony is quite to his liking - it is enough to transplant a heather bush into a planter and provide a "roof over his head."

Ornamental cabbage

Ornamental cabbage is a new favorite of landscape designers and gardeners in Russia. Unpretentiousness, frost resistance and expressive leaves that become brighter with the onset of cold weather make it an excellent solution for decorating a balcony. Ornamental cabbage easily tolerates transplanting into a container, winters well outdoors without additional insulation and is an excellent "companion" for decorative compositions in a flower pot.

Conifers and evergreens

The classics of winter gardening of a balcony in our latitudes are evergreen trees and shrubs. Dwarf spruce, pine, thuja, cedar in large pots will not only improve your view from the window, but will also become the basis for stunning Christmas compositions. Conifers in flowerpots, some snow and a couple of garlands are a traditional recipe for a good mood in winter.

Conifers in flowerpots, some snow and a couple of garlands are a traditional recipe for a good mood in winter.

Euonymus

Euonymus is an evergreen shrub or tree, the main decoration of which is bright leaves that are painted in various variations of pink, crimson and purple. Pleasing with unusual shades and fruits-boxes, which sometimes persist until the very frost. Many varieties of euonymus feel comfortable at a temperature of -35 0 C - however, only in the garden. When planted in a flower pot, the frost resistance of the plant decreases, although they are still able to withstand a small minus.

Hellebore

A beautiful winter flower that can live in a pot on a balcony up to -10 0 C. Its natural flowering starts in November and ends in spring. Expressive snow-white flowers look spectacular in flowerpots, as well as in bouquets and decorative compositions with dried flowers and moss. In severe frosts, the plant "hibernates" and looks frozen, but this impression is deceptive - the hellebore simply draws moisture from the buds to prevent them from freezing. To protect the flower from frost and temperature changes, it is recommended to cover the plant with coniferous spruce branches.

In severe frosts, the plant "hibernates" and looks frozen, but this impression is deceptive - the hellebore simply draws moisture from the buds to prevent them from freezing. To protect the flower from frost and temperature changes, it is recommended to cover the plant with coniferous spruce branches.

Outdoor balcony garden in summer

It is not a problem to decorate a balcony with plants in the spring and summer period - many plants grow well on an open balcony in the warm season. Dwarf trees in large pots, flower arrangements on the windowsill, climbing and liana-like plants falling from the brackets for hanging planters - the balcony can be turned into an urban “garden branch” (and we will definitely devote a separate article to this issue!).

If you are lucky enough to be the owner of an openwork balcony with a wrought iron railing (the so-called "French balcony"), you can place hanging flower pots outside. Such balconies are often found in buildings of the 19th century on the old streets of Moscow and other large cities. By planting spectacular fuchsias or decorating the lattice with a winding cascade of ivy, you can create a spectacular accent on the facade and collect a lot of pluses in karma from aesthetes, tourists and connoisseurs of atmospheric urban details.

Such balconies are often found in buildings of the 19th century on the old streets of Moscow and other large cities. By planting spectacular fuchsias or decorating the lattice with a winding cascade of ivy, you can create a spectacular accent on the facade and collect a lot of pluses in karma from aesthetes, tourists and connoisseurs of atmospheric urban details.

Note! If you are looking for a gift for home gardeners, take a look at houseplant gift set from the British brand Burgon & Ball in association with the Royal Horticultural Society. Unsurpassed quality and original design of tools and accessories have been the choice of British aristocratic gardeners since 1730!

Names of medicinal plants and their types, list of medicinal garden flowers

Author: Elena N. https://floristics.info/en/index.php?option=com_contact&view=contact&id=19 Category: Garden Plants Retrained: Last editing:

Content

- Iris (lat.

IRIS)

IRIS) - calendula

- LAVANDADA (LAVANDULA)

- ) (lat. Convallaria)

- Lily (lat. Lilium)

- Day lily (lat. Hemerocallis) 9Ol000 garden beer gardens is a herbaceous perennial with very beautiful dark purple and yellow flowers that grows wild only in the Transcarpathian region of Ukraine. However, in cultivation it is a very popular plant that can often be seen in gardens and lawns near houses. As a medicinal raw material, iris rhizomes are used, which have a pleasant taste and aroma. Two-three-year-old iris roots are harvested in early spring or autumn. Preparations from Germanic iris are used as an expectorant, analgesic, enveloping and anti-inflammatory agent for pneumonia, catarrhs of the upper respiratory tract, colitis, diseases of the gallbladder and liver. They are used externally to remove freckles, infected ulcers and wounds. An infusion of iris rhizomes is used to rinse the mouth with toothache, and powder from the roots is used to treat neurodermatitis.

Infusion of german iris rhizomes: Pour a teaspoon of crushed german iris rhizome with a glass of cold water and infuse for 8 hours, then strain and use for washing, lotion and rinsing.

Growing iris in the garden - planting and care

Iris tenuifolia (lat. Iris tenuifolia) is a herbaceous perennial with fragrant purple or light blue flowers. The seeds and rhizomes of the plant are used as raw materials. Apply powder from the seeds externally as a powder for soft tissue injuries accompanied by bleeding.

Iris seeds decoction: Pour 8 g of seeds with 200 ml of water and boil for a quarter of an hour in a water bath, then cool, strain, add boiled water to the original volume and take in small sips of half a glass 3-4 times a day before meals with bloody vomiting, difficulty urinating, nasal and uterine bleeding.

A decoction of the rhizomes of iris fine-leaved: Pour 40 g of crushed rhizome into 200 ml of water, cook in a water bath for 15 minutes, cool, strain, add boiled water to the original volume and drink in small sips 1/3 cup 3 times a day for menorrhagia .

Florentine iris (lat. Iris florentina) is a herbaceous perennial with yellow, pale blue or white single flowers. The medicinal properties of the Florentine iris are similar to those of the Germanic iris.

Yellowest iris, or calamus (lat. Iris pseudacorus), aka marsh iris, water iris, borage, cockerel, core, yellow water lily, wild tulip - herbaceous perennial plant with golden yellow flowers. For medicinal purposes, the leaves and rhizomes of the yellow iris are used. Preparations from yellow iris have anthelmintic, anti-inflammatory, expectorant, diuretic and hemostatic effects, therefore, crushed fresh rhizomes of the plant are used for sitz baths for hemorrhoids, an aqueous infusion of dried rhizomes is used to treat purulent wounds, ulcers, burns, rinsing the mouth with toothache and acute and chronic gingivitis, and infusion of rhizomes in sunflower oil rub the skin with myositis and arthritis.

Fresh juice from the rhizomes of iris calamus is used to treat periodontal disease, diarrhea and bleeding.

For rinsing, lotion and washing: Pour one teaspoon of dry rhizomes of yellow iris with a glass of cold water, insist under the lid for 8 hours, then strain.

- Growing viola seedlings: sowing, picking

For sitz baths: Boil 400 g grated rhizomes for 5 minutes in 4 liters of water with the lid closed, cool to 35 ºC, strain and use in baths lasting 5-10 minutes for 4-5 days.

For bleeding, diarrhea, ascites and toothache: Pour 30 g of crushed root into 200 ml of red wine, infuse for a week in a dark place, shaking daily, then strain and drink 1 tablespoon every two hours.

Calendula (lat. Calendula)

Calendula officinalis, better known as "marigolds" is an annual herbaceous plant whose yellow-orange inflorescences can be seen in every garden .

For medicinal purposes, it is the marigold baskets that contain many useful substances. Collect inflorescences from the beginning of their mass flowering until frost. Calendula officinalis is used for diseases of the gallbladder, liver diseases, colitis and gastritis. Marigold preparations calm the nervous system, lower blood pressure, have a detrimental effect on pathogens such as staphylococcus and streptococcus, heal wounds, bruises, and treat skin rashes. Tincture of calendula rinse your mouth with stomatitis and throat with sore throat. In the food industry, calendula is used to flavor and color cheeses. In cosmetology, marigold inflorescences are used to produce care products for inflamed and sensitive skin, removing freckles, treating porous skin and cracked heels.

For angina: Place 2 tablespoons of marigold inflorescences in a thermos, pour a glass of boiling water, infuse for 2-3 hours, strain and drink 1-2 tablespoons 3 times a day or use for rinsing or inhalation.

For insomnia: tablespoon of flowers pour a glass of boiling water, leave for 2-3 hours, strain and take 1 tablespoon 3 times a day and at night.

Calendula tincture: Pour 2 tablespoons of flowers into 100 ml of vodka, infuse for two weeks in a dark place, then strain.

Infusion of calendula: Pour 2 tablespoons of flowers into a glass of hot water, heat for 15 minutes in a water bath, strain and take 1-2 tablespoons warm 2-3 times a day.

- Nigella: growing from seeds, types and varieties

Calendula ointment: Mix 5 tablespoons of powdered dried marigold flowers with 200 g of melted lard or vaseline, heat in a water bath with constant stirring until smooth, cool and store in the refrigerator.

Field calendula (lat. Calendula arvensis) is an annual herbaceous plant with yellow flower heads. For medicinal purposes, the ground parts of the plant are of interest - inflorescences, leaves, stems, which have a wound healing, antiseptic, antispasmodic, astringent, diaphoretic, hemostatic, choleretic and sedative effect.

Calendula field preparations reduce reflex excitability, have a calming effect on the central nervous system, increase cardiac activity, increase the secretory and excretory function of the kidneys, improve the composition of bile, lowering the concentration of cholesterol and bilirubin in it. In traditional medicine, calendula preparations as an antiseptic and anti-inflammatory agent are used in the treatment of hepatitis, gastric and duodenal ulcers, cholecystitis, and ulcerative colitis. In gynecology, they are used as a hemostatic agent for menstrual disorders after childbirth, for erosions and ulcers of the cervix and whites. Calendula preparations are used for heart diseases, which are accompanied by palpitations, shortness of breath and swelling. Externally, tincture, infusion and ointment of calendula field are used in the treatment of burns, wounds, non-healing ulcers, fistulas, for gargling and oral cavity with follicular sore throat and stomatitis, treatment of abrasions and wounds, boils and carbuncles, barley, blepharitis and conjunctivitis.

Calendula field preparations reduce reflex excitability, have a calming effect on the central nervous system, increase cardiac activity, increase the secretory and excretory function of the kidneys, improve the composition of bile, lowering the concentration of cholesterol and bilirubin in it. In traditional medicine, calendula preparations as an antiseptic and anti-inflammatory agent are used in the treatment of hepatitis, gastric and duodenal ulcers, cholecystitis, and ulcerative colitis. In gynecology, they are used as a hemostatic agent for menstrual disorders after childbirth, for erosions and ulcers of the cervix and whites. Calendula preparations are used for heart diseases, which are accompanied by palpitations, shortness of breath and swelling. Externally, tincture, infusion and ointment of calendula field are used in the treatment of burns, wounds, non-healing ulcers, fistulas, for gargling and oral cavity with follicular sore throat and stomatitis, treatment of abrasions and wounds, boils and carbuncles, barley, blepharitis and conjunctivitis. Infusion of calendula in folk medicine is also used to treat hepatitis, hypertension, cholecystitis, rickets, cardiac neuroses, and externally - for baths, lotions, washings and compresses for frostbite, fistulas, non-healing ulcers, boils and skin rashes.

Infusion of calendula in folk medicine is also used to treat hepatitis, hypertension, cholecystitis, rickets, cardiac neuroses, and externally - for baths, lotions, washings and compresses for frostbite, fistulas, non-healing ulcers, boils and skin rashes. How to grow calendula in the garden - sowing and care

Infusion of field calendula for hypertension: Pour 1 tablespoon of chopped dry herb with a glass of boiling water, leave for 2 hours, then strain and take 1-2 tablespoons 3 times a day.

Calendula decoction for jaundice, cholecystitis and hepatitis: Pour 3 tablespoons of flowers into two glasses of water, boil for 3-4 minutes on low heat, leave for 1 hour, strain and take a quarter of a glass 3 times a day.

Field marigold tincture: Pour 10 g of marigold flowers into 100 ml of 70% alcohol, seal tightly and leave in a dark place for a week, then strain. Application:

- 20-25 drops 3 times a day half an hour before meals for gastric and duodenal ulcers;

- dilute a teaspoon of tincture in a quarter glass of water and rinse your mouth and throat with sore throat and stomatitis;

- moisten gauze with tincture and apply to wounds, ulcers, burns and boils.

Calendula ointment: Mix 5 g of calendula tincture thoroughly with 25 g of vaseline.

Lavender (lat. Lavandula)

Lavender officinalis (Lavandula officinalis), or real lavender from the Lamiaceae family - a shrub with bright bluish-violet flowers, which are the main plant virtues from the point of view of medicine . Collect inflorescences a week or two after the start of flowering. The most valuable product from lavender is its oil, which has antimicrobial properties and is widely used to treat burns, wounds, cuts and skin diseases. A decoction and infusion of lavender flowers are used as a mild sedative and antispasmodic for neurasthenia, migraines, neuralgic pains, inflammation of the middle ear, and as a choleretic agent.

- The most beautiful shrubs for a summer cottage

Infusion of lavender flowers: Pour 3 teaspoons of flowers into 400 ml of boiling water, leave for 10 minutes, strain and drink throughout the day.

Bronchitis remedy: Mix 2 drops of lavender oil with a teaspoon of honey and eat with cough.

Lavandula angustifolia, or pinnate, or spiky is a perennial subshrub with purple-violet flowers collected in terminal spike-shaped inflorescences. As a raw material for the medicine, lavender leaves are of interest, which are harvested when most of the flowers bloom on the inflorescences. Angustifolia lavender oil has antiseptic properties and is used to treat wounds, burns, and skin diseases. Preparations from flowers are prescribed as an antispasmodic and sedative for gastrointestinal colic. An infusion of angustifolia lavender flowers is a carminative and analgesic, recommended for pain in the intestines or stomach. Externally, lavender flowers are used for baths and aromatic pillows, they are also added to salads, hot dishes and drinks. Crushed leaves, flowers and stems of lavender are used to make scented candles that drive mosquitoes and mosquitoes out of the room, and the aroma of dried inflorescences repels moths.

Essential oil is used for rubbing with neuralgia, gout and rheumatic pains. In the alcoholic beverage industry, lavender essential oil is widely used to flavor wines.

Essential oil is used for rubbing with neuralgia, gout and rheumatic pains. In the alcoholic beverage industry, lavender essential oil is widely used to flavor wines. Growing and caring for lavender from seed

For migraine, palpitations and irritability: Pour 3 teaspoons of lavender flowers into 2 cups of boiling water, leave for 20 minutes, strain and take half a cup 2 times a day.

For indigestion and colic: Pour 1 tablespoon of lavender flowers into a glass of boiling water, leave for 10-20 minutes, strain and drink 3-4 times a day for a teaspoon.

For insomnia: Put 100 g of flowers in a bag made of natural fabric and store it in a plastic bag, and in case of insomnia, warm it up, remember it in your hands and fall asleep with it.

Lavender oil: combine 1 part of crushed lavender flowers with five parts of sunflower or olive oil, infuse for 1-2 months in the dark in a tightly closed vessel, then strain and use as an analgesic.

Lavender infusion: Pour a tablespoon of lavender flowers into a glass of boiling water, leave for 5-10 minutes, strain.

Lavender bath: Pour 5-6 tablespoons of flowers with one liter of cold water, bring to a boil, leave for 10 minutes, strain and pour into the prepared bath.

Lily-of-the-valley (lat. Convallaria)

May lily-of-the-valley (lat. Convallaria majalis), aka vannik, culprit, convalia, field lily, rejuvenator is a well-known perennial herbaceous plant. For medicine, its flowers, leaves and grass are of interest. Leaves are harvested at the stage of budding, flowers and grass - during flowering. All ground parts of the lily of the valley contain cardiac glycosides, essential oil, alkaloids, starch and organic acids. Cardiac glycosides of lily of the valley normalize the work of the neuromuscular apparatus of the heart, hemodynamics, they have a sedative effect. Preparations of the May lily of the valley in combination with other sedative or cardiac drugs are used for heart failure and neuroses.

Clinical observations have shown that lily of the valley preparations interact most effectively with hawthorn root and valerian. In folk medicine, lily of the valley is used to treat heart diseases, nervous diseases and shocks, insomnia, fever and some eye diseases. As a sedative, lily of the valley preparations are best combined with motherwort, valerian or hawthorn.

Clinical observations have shown that lily of the valley preparations interact most effectively with hawthorn root and valerian. In folk medicine, lily of the valley is used to treat heart diseases, nervous diseases and shocks, insomnia, fever and some eye diseases. As a sedative, lily of the valley preparations are best combined with motherwort, valerian or hawthorn. Infusion of May lily of the valley leaves: pour a teaspoon of crushed leaves into a glass of boiling water, leave for 40 minutes, strain.

Planting and caring for lilies of the valley in the garden

Lily (lat. Lilium)

Lily (lat. Lilium) is a perennial herbaceous bulbous plant of the Liliaceae family.

White lily (lat. Lilium candidum) is a perennial with large fragrant white flowers collected in a racemose inflorescence. Of interest are lily bulbs harvested during the dormant period, as well as leaves and flowers that are harvested during flowering.

White lily bulbs have analgesic, diuretic and emollient effects. Fresh bulbs in crushed form are applied to soften hard, inflamed swellings on the skin. Water infusion of flowers of the plant wash the face.

White lily bulbs have analgesic, diuretic and emollient effects. Fresh bulbs in crushed form are applied to soften hard, inflamed swellings on the skin. Water infusion of flowers of the plant wash the face. White lily bulb tincture: Pour 100 ml of crushed bulbs into 300 ml of alcohol, cork well and infuse in a dark place for 2 weeks. Strain and take a teaspoon with 50 ml of water before morning and evening meals. Indications: shortness of breath with sputum.

Tonic: 100 g of fresh crushed white lily flowers are infused in a dark place with 500 ml of vodka for 2 weeks, then filtered and taken 20-50 ml in case of chronic fatigue.

White lily bulb ointment: 2 tablespoons of crushed bulbs and 2 tablespoons of crushed lily flowers are poured into 150 ml of olive oil and infused in the sun for three weeks, then filtered and used for rubbing against cramps, pains and as a cosmetic means.

Planting and caring for lilies in the garden - how to grow

Curly lily (Lilium martagon), or variegated lily, aka royal curls, perennial forest lily, golden root whitish-red flowers with dark spots inside.

Bulbs, flowers and leaves of the plant are of value. Leaves and flowers are harvested in June-July, and bulbs in April or October. Lily martagon is used only in folk medicine: tincture is used as a sedative for depression and nervous breakdowns, as well as an analgesic for toothache. A decoction of wild lily flowers helps with diseases of the gallbladder. The leaves, which have a wound healing and anti-inflammatory effect, are applied to burns and wounds in the form of lotions.

Bulbs, flowers and leaves of the plant are of value. Leaves and flowers are harvested in June-July, and bulbs in April or October. Lily martagon is used only in folk medicine: tincture is used as a sedative for depression and nervous breakdowns, as well as an analgesic for toothache. A decoction of wild lily flowers helps with diseases of the gallbladder. The leaves, which have a wound healing and anti-inflammatory effect, are applied to burns and wounds in the form of lotions. LILENIC (lat. Hemerocallis)

Lileynik Small (lat. Hemerocallis minor), or Beauty, or 9002 or yellow lilia - grassy perennial flowering color. As a raw material for medicinal preparations, the flowers of the plant are used, which are harvested during the flowering period, but sometimes daylily leaves are also useful. The flowers have an antipyretic, hemostatic, tonic and wound-healing effect, and a decoction of the leaves and an infusion of fully blooming daylily flowers in folk medicine treat liver diseases.

In Tibetan medicine, a decoction of blooming daylily flowers is used as a wound healing and tonic heart remedy, an aqueous infusion of the herb is used for fever, and an infusion of stems and leaves is used for jaundice. As an external agent, a decoction of flowers is used to wash burns. A decoction of rhizomes helps well in the treatment of female diseases, and daylily roots rolled in a meat grinder are used for lotions and compresses for various tumors.

In Tibetan medicine, a decoction of blooming daylily flowers is used as a wound healing and tonic heart remedy, an aqueous infusion of the herb is used for fever, and an infusion of stems and leaves is used for jaundice. As an external agent, a decoction of flowers is used to wash burns. A decoction of rhizomes helps well in the treatment of female diseases, and daylily roots rolled in a meat grinder are used for lotions and compresses for various tumors. Infusion of daylily leaves and stems: Pour two cups of boiling water over a tablespoon of daylily leaves and stems, infuse for 4 hours, then strain and take half a cup 4 times a day.

How to grow daylilies in the garden - planting and care

Decoction of full-blown daylily flowers: Pour 10-20 g of flowers into a glass of water, warm over a fire for 10 minutes, strain and take 3 times a day for a tablespoon.

Snapdragon (lat. Antirrhinum)

Snapdragon (lat.

Antirrhinum), or cat's eye, or lion's mouth two-color coloring, collected in a brush. As a medicinal raw material, the entire ground part of the snapdragon is used, which is harvested during flowering. Antirrinum in the form of gruel for lotions and compresses is used for non-healing wounds, furunculosis, fungal infections. It is also used for baths. A decoction of snapdragons is useful for inflammation of the eyelids and eyes.

Antirrhinum), or cat's eye, or lion's mouth two-color coloring, collected in a brush. As a medicinal raw material, the entire ground part of the snapdragon is used, which is harvested during flowering. Antirrinum in the form of gruel for lotions and compresses is used for non-healing wounds, furunculosis, fungal infections. It is also used for baths. A decoction of snapdragons is useful for inflammation of the eyelids and eyes. Growing snapdragons from seeds in the garden

Mallow (lat. Malva)

Common mallow (lat. Malva rosea), or perennial culture. Mallow reaches a height of 1 to 2.25 m. Mallow flowers, often double, up to 7.5 cm in diameter, form terminal spike-shaped inflorescences with large petals, on which delicate mesh veins appear, and can be painted in different colors. For medicinal purposes, plants with darker flowers are selected - black and red.

Infusion of mallow flowers has a softening and enveloping effect, increases secretion. It is prescribed for gastritis, bronchitis and is used externally for gargling with sore throat.

Infusion of mallow flowers has a softening and enveloping effect, increases secretion. It is prescribed for gastritis, bronchitis and is used externally for gargling with sore throat. Planting and caring for mallow in the garden

Infusion of mallow flowers: Pour 2 tablespoons of mallow flowers into 100 ml of boiling water, infuse for an hour in a dark place, strain and take 4 times a day for a tablespoon.

Narcissus (lat. Narcissus)

Poetic daffodil (lat. Narcissus poeticus) Both the ground part of the narcissus, which is harvested in July, and its bulb are used as raw materials. The bulbs and leaves of the plant contain the alkaloid lycorine, which promotes sputum discharge, facilitating the course of pneumonia and bronchitis. Homeopaths for the manufacture of medicinal preparations use the essence of flowering daffodils. Narcissus preparations are used to treat inflammatory processes of the skin and subcutaneous tissue, as well as tumor formations.

They also help with mastitis, and narcissus oil is also used as an external remedy for pain in the knees, hemorrhoids and sciatica.

They also help with mastitis, and narcissus oil is also used as an external remedy for pain in the knees, hemorrhoids and sciatica. Narcissus bulb lotion: crushed bulb is mixed with an equal amount of boiled rice and applied to the inflamed area of the body in case of mastitis - as a result, the temperature quickly decreases, swelling decreases and pain gradually disappears. Lotions are also used on boils and carbuncles.

Growing daffodils outdoors - planting and care

Narcissus pseudonarcissus, or yellow, also belongs to the Amaryllis family and is a herbaceous bulbous perennial with a single yellow flower. As a raw material, the entire ground part of the false narcissus is used, which contains valuable medicinal substances - the alkaloid narcisin, tannin, inulin, essential oil, waxes, fatty oil and other elements. The herb of false narcissus is harvested during flowering. Plant preparations have antitussive and expectorant effects.

Narcissus tincture false: one part of dry chopped narcissus herb is insisted on 10 parts of vodka in a dark place for 10 days, after which it is filtered and taken 3-4 times a day, 3-10 drops for bronchitis, severe cough, diarrhea, vomiting and headache in the area forehead.

Nasturtium (lat. Tropaeolum)

WATTER (Latin Tropaeolum Majus), or Kapucin Big, or MAYASKASIS, or 9002 or KRISS, KRUSS.0021 or Flower cress is an annual herbaceous plant of the Nasturtium family with orange flowers. For medicinal purposes, flowers, fruits and leaves of nasturtium are used, which have anti-inflammatory, anti-scorbutic, diuretic and metabolic-accelerating effects. The immature fruits of nasturtium taste like capers, but in addition to nutritional value, they have a strong antiscorbutic effect. The fruits, like the leaves of nasturtium, contain a large amount of ascorbic acid, therefore, among the people, a decoction of these parts of the plant, mixed with herbs of a similar effect, was used for scurvy.

And if nasturtium flowers are boiled with honey, they can cure children's thrush. Nasturtium herb infusion is indicated for anemia, skin rashes and kidney stones.

And if nasturtium flowers are boiled with honey, they can cure children's thrush. Nasturtium herb infusion is indicated for anemia, skin rashes and kidney stones. Decoction of nasturtium: Pour 20 g of crushed flowers and leaves of the plant into 200 ml of boiling water, simmer for 5 minutes, cool, strain and take 2-3 tablespoons three times a day.

Growing nasturtium from seeds in the garden - planting and care

Decoction for scurvy: Mix nasturtium juice with an equal amount of dandelion juice and tripol, add 200 ml of the mixture to 200 ml of whey, simmer for 10 minutes, cool and take 2-6 tablespoons 1 to 3 times a day.

Stonecrop (lat. Sedum)

Large sedum (lat. Sedum telephium), or bean grass, divine color, hare grass, creaker, six-week-old herbaceous perennial of the Crassulaceae family with greenish-yellow or red flowers, collected into terminal corymbose panicles. The medicinal raw material is the herb of the plant, which is harvested throughout the summer, and fresh stonecrop juice.

In folk medicine, stonecrop herb is used as a tonic and tonic when the body is weakened, and the juice is used for chronic diseases of the gallbladder and liver, as well as for coronary heart disease. Outwardly, the grass is used for washing and lotions on burns and wounds and for removing calluses and warts, which, with prolonged application of stonecrop leaves, turn white and fall off. Fresh stonecrop juice massages weak and bleeding gums.

In folk medicine, stonecrop herb is used as a tonic and tonic when the body is weakened, and the juice is used for chronic diseases of the gallbladder and liver, as well as for coronary heart disease. Outwardly, the grass is used for washing and lotions on burns and wounds and for removing calluses and warts, which, with prolonged application of stonecrop leaves, turn white and fall off. Fresh stonecrop juice massages weak and bleeding gums. Planting and caring for stonecrop in the garden

Stonecrop (lat. Sedum acre), or hernia herb, goose soap, juveniles, heart grass, kernelweed - a low herbaceous perennial of the Crassidaceae family. Stonecrop has bright yellow flowers located in the axils of the leaves. This plant is a honey plant. As a medicinal raw material, the entire ground part of the stonecrop is used. A decoction of sedum grass was used for nervous disorders, hypotension, diseases of the stomach and upper respiratory tract. It was used externally to heal wounds and ulcers.

An ointment based on fresh herb sedum and fat is used to treat lichen, carbuncles, hemorrhoids and eczema.

An ointment based on fresh herb sedum and fat is used to treat lichen, carbuncles, hemorrhoids and eczema. Rhodiola rosea (lat. Sedum roseum), or golden root, rose root, pink stonecrop is a herbaceous perennial with a rhizome that has a bitter astringent taste and aroma of rose oil. Small golden-yellow, reddening when ripe, flowers are collected in terminal corymbose inflorescences. For medical purposes, the tuberous rhizome of the plant is used, which contains tannins, essential oil, organic acids - gallic, oxalic, citric, succinic and malic, a significant amount of sugars, fats, waxes, sterols, proteins and other useful substances. Collect rhizomes from the second half of July to mid-August. Rhodiola preparations have a pronounced stimulating effect, increase efficiency, normalize metabolic processes in the body and improve energy metabolism in the brain and muscles due to oxidative processes. Rhodiola stimulates mental activity, improves memory and attentiveness.

It, like ginseng, has adaptogenic properties. In the course of clinical studies, Rhodiola rosea extract showed good results in the treatment of neurosis, hypotension, schizophrenia with asthenic remission. In folk medicine, alcohol tincture of Rhodiola rhizome has been successfully used for more than 400 years for stomach diseases, impotence, malaria, nervous diseases, loss of strength and overwork as a tonic and tonic. The golden root is also indicated for asthenic conditions, insomnia, various neuroses, physical exhaustion, increased irritability, and hypotension. Externally, the extract of Rhodiola rosea is used as an effective wound healing agent for pyorrhea, cuts, and for gargling the throat and mouth with tonsillitis.

It, like ginseng, has adaptogenic properties. In the course of clinical studies, Rhodiola rosea extract showed good results in the treatment of neurosis, hypotension, schizophrenia with asthenic remission. In folk medicine, alcohol tincture of Rhodiola rhizome has been successfully used for more than 400 years for stomach diseases, impotence, malaria, nervous diseases, loss of strength and overwork as a tonic and tonic. The golden root is also indicated for asthenic conditions, insomnia, various neuroses, physical exhaustion, increased irritability, and hypotension. Externally, the extract of Rhodiola rosea is used as an effective wound healing agent for pyorrhea, cuts, and for gargling the throat and mouth with tonsillitis. It is possible to use drugs prepared according to the recipes described in the article only after consulting a doctor!

Read the continuation of the article about medicinal plants.

Literature

- Learn more

- Top front door colors

- When should i prune my japanese maple

- Kelly hoppen lighting

- Ryan murphy provincetown

- Royal blue couch living room ideas

- How do you grow a mango tree from seed

- Cost of a front door

- Living room conservatory ideas

- Vegetable food processor

- Indoor air purifier plants

- Farmhouse bedroom furniture ideas